Oscar Wilde, pedophile and predator

Oscar Wilde, pedophile and predator I strongly object to Oscar Wilde's being marketed as some kind of figurehead for gay and lesbian theatre activists. And I object to gay men's attempts to unilaterally define what is touted to the media as coalition culture. And I object most strongly of all to what I call lesbian "theatre wives," who, for the questionable privilege of a male-funded theatre roof over their heads are willing to table women's issues in favor of those which speak to the interests of their theatre husbands.

Oscar Wilde is a case in point. His "culture" - arrogantly classist, misogynist, pedophilic - shares nothing in common with lesbian-feminist values, and as lesbians we need to be knowledgeable about the facts before we join our gay brothers in celebrating as a martyr someone whom many of us would consider a criminal.

Constance Wilde

Constance Wilde Furthermore, it was Wilde's homophobia that set the whole legal process in motion in the first place! His lover's father "accused" Wilde of homosexual behavior, and Wilde, in a fit of pique and egged on by his narcissistic lover, sued the man for libel - in other words, for lying. Hardly a stand for gay rights!

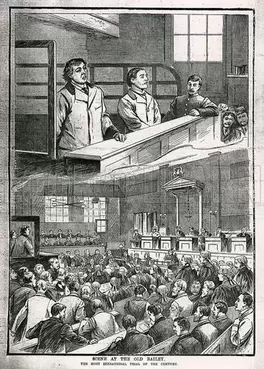

And here is Wilde retaining an attorney for his suit:

Sir Edward Clarke advised him, "I can only accept this brief, Mr. Wilde, if you can assure me on your honour... that there is no and never has been any foundation for the charges that are made against you." Wilde stood up and declared the charges "absolutely false and groundless." It is important to remember that Wilde was prosecuting, and that Clarke, like most attorneys, was not interested in taking on an unwinnable case. To his credit, Sir Edward continued to defend Wilde through his subsequent trials, even after he discovered how his client's deliberate duplicity had placed him on the losing side of a sordid and sensational case which became known as the "trial of the century." The suit proved such a professional embarrassment to him, Clarke omitted any mention of it in his memoirs.

And what about his family? Wilde was married with two children at the time that he instigated the frivolous libel suit. It was an action taken without consulting his wife and without the funds to pay the legal fees. Foolishly, Wilde trusted his lover to cover the costs. After his incarceration, his creditors moved in, and his family's possessions - even the children's toys - were ruthlessly auctioned off. His wife, compelled by the scandal to leave England, found that it was necessary to change her name and her sons' names even to obtain lodging in a foreign hotel.

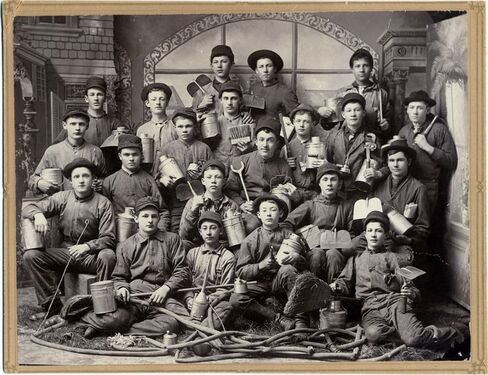

Vyvyan and Cyril, Wilde's sons

Vyvyan and Cyril, Wilde's sons As a footnote to the marriage, Wilde had not had sexual relations with Constance for several years. The reason he had given was that his syphilis, which he had contracted from a prostitute during his student years and had believed to be cured, was, in fact, still virulent. There is no evidence that Wilde ever shared this information with any of the boys with whom he had sexual relations.

Wilde was brought to bankruptcy while in prison when his lover's father brought suit to recover his damages from the ill-advised libel suit. Not only did Lord Alfred, Wilde's lover, renege on his agreement to cover these costs, but as Wilde reminded him in his famous letter "de Profundis," this parsimony was all the more reprehensible, because Wilde had squandered many times that amount on Lord Alfred.

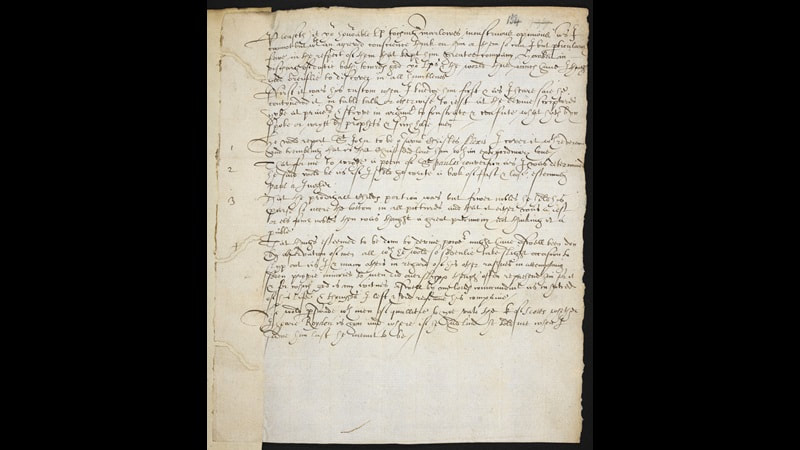

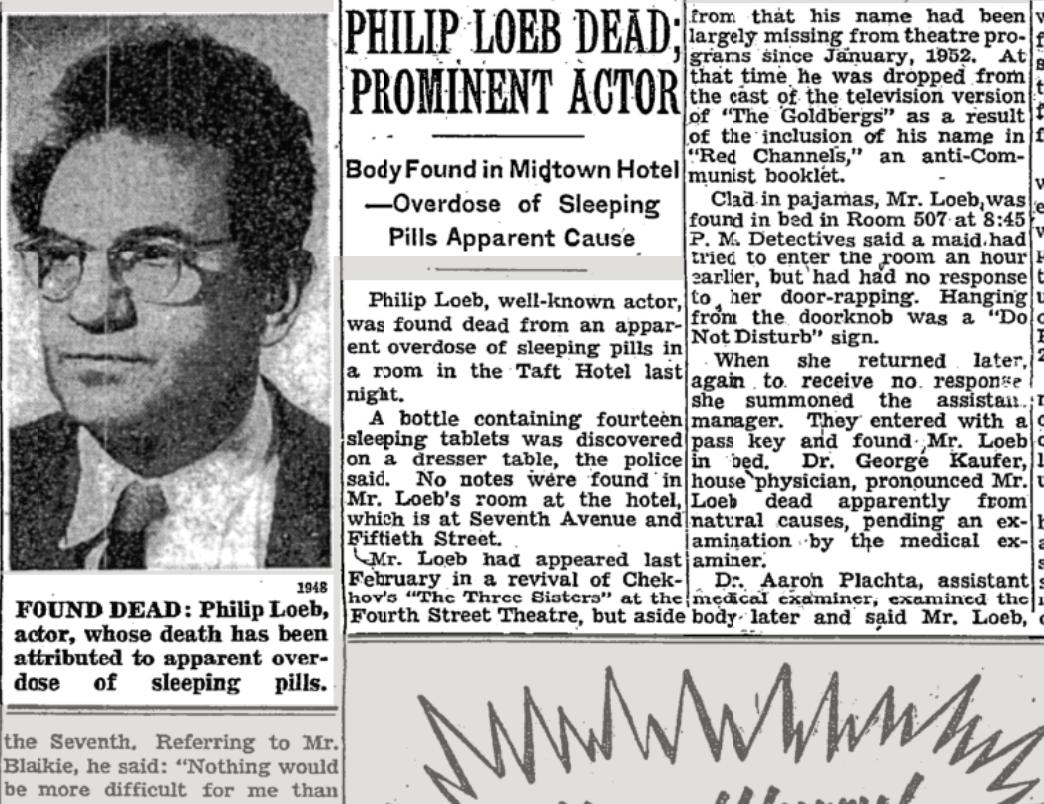

Illustration from the trial, with Oscar Wilde and his procurer Alfred Taylor in the dock

Illustration from the trial, with Oscar Wilde and his procurer Alfred Taylor in the dock And at this point, a number of my gay brothers will insist that I make a distinction between "child prostitute" and "teenaged prostitute." I confess that the distinction is lost on me, and I will leave it to those for whom qualifiers of age, class, geography, period in history, etc. provide a certain rationale, if not outright justification, for a practice which is apparently so intrinsic a part of gay male culture and so violently antithetical to lesbian-feminist values.

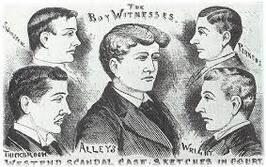

Some gay brothers will also jump to Wilde's defense, claiming that the boys were being paid by the defendant to testify, either that, or cooperating with the state in order to avoid prosecution. That some of these boys had histories of blackmailing their "clients" has also been used to discredit their testimony. Leaving for a moment the fact that Wilde admitted to friends on several subsequent occasions that the charges had been true, let us look at these objections.

"Boy witnesses" from an earlier London trial involving child prostitution

"Boy witnesses" from an earlier London trial involving child prostitution The relationship between the john and the prostituted boy is not a mutual one. It is the standard method of operation for colonialists, enslavers, and pimps, to brutalize the members of an underclass created by economic and sometimes social violence, and then to point to their brutalization as a rationale for the conditions to which they are subjected. This circular and self-serving logic is in play when Wilde's defenders attempt to discredit his victims as "blackmailers and thieves."

Wilde gave a speech during the trial, which is often cited as a testimonial to his gay pride. In fact, he gave the speech as an attempt to prove that his relations with Lord Alfred were not gay, but rather a platonic bonding between an older man and a younger man. The context in which he framed his famous "love that dares not speak its name" speech was profoundly homophobic.

This is difficult to believe when, on one occasion, Wilde picked up a boy who sold newspapers, and took him to a hotel in Brighton for a weekend. In order to disguise the obvious nature of the relationship, Wilde bought the boy a suit of clothing with insignia that would associate him with a prestigious private boys' school. In court, he insisted that the choice of the school's colors had been the boy's.

In fact, Wilde was very class-conscious. In "de Profundis," he told a very different story - and one in which class difference features prominently:

To what does "poison" refer if not their class antagonism towards Wilde and his kind? And what a patriarchal reversal of the power relations! It is remniscent of the rhetoric used against incest victims, characterizing them as promiscuous and vampiric.

One of the boys who testified had not been procured for Wilde. He had been employed as an office boy at Wilde's publishing firm, and Wilde had cultivated the friendship by exploiting the boy's interest in his writing. The boy testified that he had been ignorant of Wilde's intentions, that he was traumatized by the sexual contact, and that he was subsequently fired from his job for his association with Wilde. His emotional confusion about his victimization by a "benign" perpetrator was used against him in court as proof that he was crazy.

After his conviction, and halfway through his two-year prison sentence, Wilde wrote the following words in a petition to the Home Secretary. No doubt the homophobia is exacerbated by his desire to win a pardon, but Wilde's attempt to characterize his homosexuality as a disease or the result of bad company is cowardly to say the least:

Hardly a gay rights manifesto.

And after prison? Wilde went to Paris, where he rendez-voused with Lord Alfred, who was being serviced sexually at the time by a fourteen-year-old boy who sold flowers on the street. This boy claimed to be "keeping" a twelve-year-old at home, and Lord Alfred was attempting to gain sexual access to the boy. Wilde himself, in the words of his lover, was "hand in glove with all the little boys on the Boulevard."

I cannot imagine a lesbian couple deliberately choosing a vacation spot where economic violence and/or colonization has created an underclass of girls who are coerced into selling their bodies to wealthy women tourists. I cannot imagine this loving lesbian couple buying these little girls and exploiting their poverty for the purposes of sexual self-gratification. And I cannot imagine two lesbians experiencing this exploitation as a pleasurable and harmless recreational activity around which they could bond.

Oscar Wilde was a pedophile, a woman-hater, a colonialist, a classist, a coward, and a colossal liar. The record speaks for itself. I call upon my gay brothers to drop the euphemisms surrounding the culture of prostitution and child sexual abuse, and to come out of denial about the nature of the men who participate in that culture.

[If you found this blog interesting, I have another about Wilde... "Oscar Wilde:His Father's Son."]

RSS Feed

RSS Feed