And you thought this was going to be about food . . .

Bear with me, because the food chain we all learned about in grade school is on the brink of becoming the food potluck—a paradigm shift so major that it’s going to make the discovery of fire look like an evolutionary weenie roast. What we are witnessing is the closing down of our homo sapiens executive dining room in favor of a more democratic, more inclusive, inter-species, employee lunchroom. And it’s all about the “Gaia Concept.”

So just what is this “serial endosymbiosis” that Margulis is talking about? In a nutshell, it’s a theory about relationships not just between plants and animals, but also between them and atmospheric gases, surface rocks, and water, which she maintains are regulated by the growth, death, integration and other activities of living organisms. In other words, it’s about the entire ecosystem of the Earth’s surface as a series of interacting ecosystems, which is definitely not your grandmother’s theory of evolution.

Dude, I think you got it wrong...

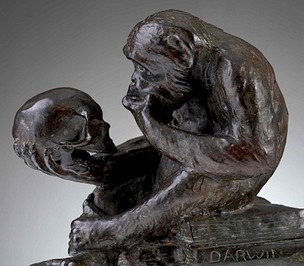

Dude, I think you got it wrong... In 1859, Charles Darwin published The Origin of the Species, the book that made a monkey out of creation theory. Darwin’s theory of evolution was about survival of the fittest: Random genetic mutations would lead to “natural selection,” whereby the more rugged or adaptive species would multiply and be fruitful, while the less rugged, less adaptive species would die out. In other words, according to Darwin, competition was good for us. This notion led to something called “Social Darwinism,” a convenient rationale for the rampant and predatory capitalism that characterized the Industrial Revolution and which continues, under various guises, to manifest itself today.

But, Margulis has looked at the numbers, and they just don’t add up. She makes the point that genetic mutations, although common and easy to induce, rarely lead to changes that are beneficial to the organism. In other words, one’s chances for becoming the lucky host of an advantageous change in DNA structure are considerably worse than those for winning the lottery—and the chances are even slimmer of becoming the founder of a new species, based on such a rare mutation.

Lessons from Lichen

Lessons from Lichen In explaining to the lay person how symbiosis works, Margulis uses the example of lichen. Lichen is a combination of two organisms living in a mutually beneficial arrangement. Most of the lichen is composed of fungal filaments, but among these filaments are green algal cells. If the lichen is submerged in water, the fungus will die out and the algae will proliferate. On the other hand, if there is an inadequate amount of sunlight to sustain the algae’s photosynthesis, then it will die out, leaving the fungus to its own devices. The algae gains a structure that enables it to live on land, and the fungus benefits from the food-making capacity of the algae.

Moving to mammals for her examples of symbiosis, Margulis describes the cow, not as an entity, but as a fifty-gallon fermentation vat. The cow does not digest the grass it eats. The grass is digested by the organisms that are growing—yes, symbiotically—inside its gut.

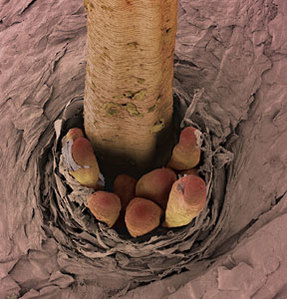

Eyelash Mites (yes, you have them)

Eyelash Mites (yes, you have them) The colon is host to the bacteria that constitute the largest percentage of the dry weight of the human body. And whether we like it or not, these bacteria constitute a de facto Lower GI Tract Tenants’ Association. When we are not eating with proper symbiotic respect for the needs of the bacteria in our gut, they die out or the more harmful ones proliferate, and we find, like most landlords, that unhappy tenants have a way of making their problems into problems for the landlords. Unhappy colon bacteria can form pockets of resistance, trash the place, or stage a sit-down strike.

The early 21st century has seen an unprecedented breakdown in communication between the bacterial tenants’ association and the landlord homo sapiens. Perhaps in a simpler time and place, when the human scavenger’s choices were narrowed to a unripe yam, a ripe yam, or a rotten yam, the bacteria had less to fear from the appetites of the landlord. But in the year 2002, the human forager faces a staggering array of substances for ingesting. Notice, I say “substances,” not “food.” There was actually a time when the food industry granted an award for the “invention” of foods from substances not usually considered edible. Cool Whip forever distinguished itself by being the first, and subsequently most difficult to top, recipient. Even when the substances ingested are the more traditional fruits and vegetables of the human habitat, the consumer discovers that these have been “enhanced” with dyes, their shelf lives have been extended by the use of preservatives, the crop yield has been multiplied by dousing with pesticides, and, most recently, unnatural selection via genetic engineering has been imposed in the name of some surreal, corporate survival of the fittest—which the Supreme Court now informs us have the legals rights of persons.

Our intestinal bacteria, which are the product of hundreds of thousands of years of non-corporate evolution, are at a loss to come up with the one-in-a-bazillion kind of genetic mutations that might, over eons, enable them to adapt to what we are eating today.

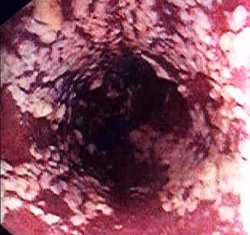

An intestine with yeast overgrowth.

An intestine with yeast overgrowth. Auto-immune diseases and allergies, especially food allergies, are on the rise, and we have arrived at the endgame of the food chain. Having arrogantly constructed a theory of consumption that places us at the top of the heap, we have made the potentially fatal error of overlooking our dependence on micro-organisms. The food chain theory goes like this: We eat the big animals who eat the little animals who eat the big plants who eat the little plants, and so on back to the pond scum. (Did somebody say “spirulina?”) We have deluded ourselves into believing that, as long as we humans continued to pay out thousands of dollars to have our bodies incinerated after death or pickled in toxic preservatives, we could lay claim to a dubious, but unique status in the animal world as the only species that eats, but is never eaten.

Kimchi, sauerkraut, yogurt, kefir to the rescue!

Kimchi, sauerkraut, yogurt, kefir to the rescue! But Darwinism is failing us. We have made valiant efforts to colonize our native bodies, imposing our artificially-manipulated, corporately-driven, commercial consumerism on the inhabitants of our various viscera. We have even come up with systems of psychology, spirituality, and philosophy to rationalize this new territorial imperative: We believe that our illnesses are the result of repressed psychological needs, of abuse at the hands of our dysfunctional families, of previous karma from past lives, of negative thinking. We bring in ever more drastic implements of surgical intervention, ever more bewildering and toxic medications—anaesthetizing or poisoning our grumbling constituencies into silence and provoking new conflagrations among previously peaceful inhabitants.

We are having as much difficulty controlling our colonies as Great Britain was having controlling theirs at the turn of the previous century, and our evolution will force us to the same conclusion: We cannot afford our colonies. Humans have no new colons to conquer. Much as it offends our theories of species superiority, we must yield to the demands of the native, single-cell organisms to whom we owe our health, whom we have systematically oppressed, and who have consistently demonstrated not only more intelligence in their operations (“wisdom” is not too strong a word), but who have also held the high ground morally, in sustaining an ethic of cooperation, shared benefits, and input from all levels of production—even with all the forces of late-twentieth-century agribusiness and biotechnology arrayed against them.

We have lost our free lunch, but what we will be gaining at the interspecies potluck is an incredible pooling of diverse resources. We will find ourselves allies, where formerly we could only dream of domination. Listening to other species as if our lives depend on it—which they do—we stand on the threshold of undreamed of modes of communication. And the devastating isolation of predatory individualism that has bred so much paranoia, insecurity, and desperation will break up when we begin to understand that we have never been alone, that we have always lived—even in our most delusional, destructive grandiosity—in symbiotic relation to all of the other forms of life on this planet, and in symbiotic relationship with the very earth, air, and water itself.

Surrendering our crowns as kings and queens of the species, we will apply ourselves diligently to winning the true crown of the creation pageant—that which is awarded for most congeniality. As the models for property ownership yield to an understanding of the responsibilities of stewardship, our orientation toward food will undergo a natural evolution. And eating what best supports symbiosis, we may just acquire a taste for life.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed