But first… What is winter burn?

Yesterday I posted a photo of one of my rhododendrons on social media, asking if anyone could tell me what was wrong with it. Half of the topmost leaves were turning brown on the ends. Up close, the brown party actually looked like shoe leather.

But… the miracle of social media! A friend of mine, whose son is a professional gardener, explained to me that what I was seeing was the result of winter burn.

She explained that winter burn was a condition that develops in winter (duh), and it happens when there has been an unseasonably warm spell… maybe just a day or two. In the fall, this warm spell would delay the onset of plant dormancy, but in the case of my rhodies, it did the opposite. The warm spell was in early spring, and what it did was bring the top leaves out of dormancy.

Because the warm spell was so brief (just a day or two), it was not enough to warm up the roots and bring them out of dormancy. The rhodie roots were pretty clear that early March in Maine was no time to wake up. But, unfortunately, the leaves fell for it. They did wake up and were all ready for action. They started opening for business and waiting for the roots to send up some water… but the roots were unable to deliver. As a result, the leaves underwent a sudden and severe drought condition, causing the outer edges of the top leaves to turn brown and curl up.

But… what’s the human analogy—the lesson to be drawn, if you will?

Frozen roots and thawing leaves. Do humans experience a kind of “winter burn” for opening ourselves up to the warmth of human interactions before our roots have had time to thaw? I think we do.

I experienced a traumatic childhood, and it took me decades to understand and heal from the effects of it. Clinically, I had complex post-traumatic stress syndrome. It’s a syndrome, not a disorder, because it’s actually a natural and functional response to chronic adverse conditions, especially in childhood. Something like plant dormancy to ride out a frozen winter.

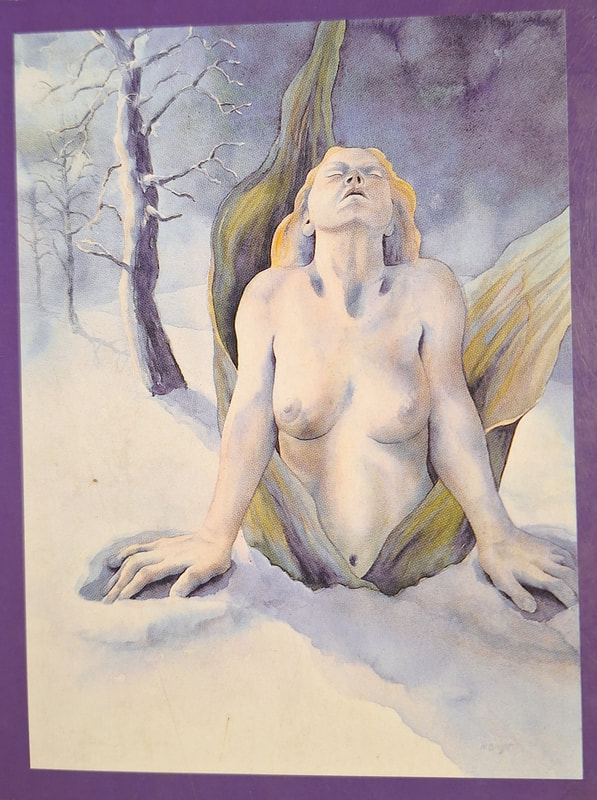

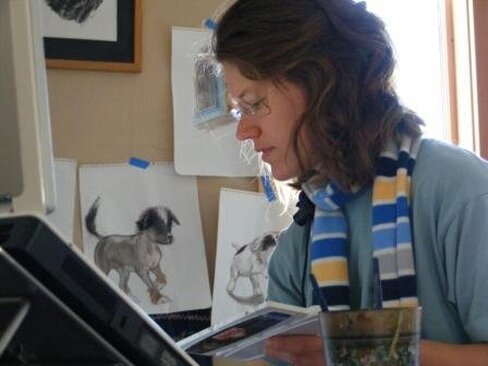

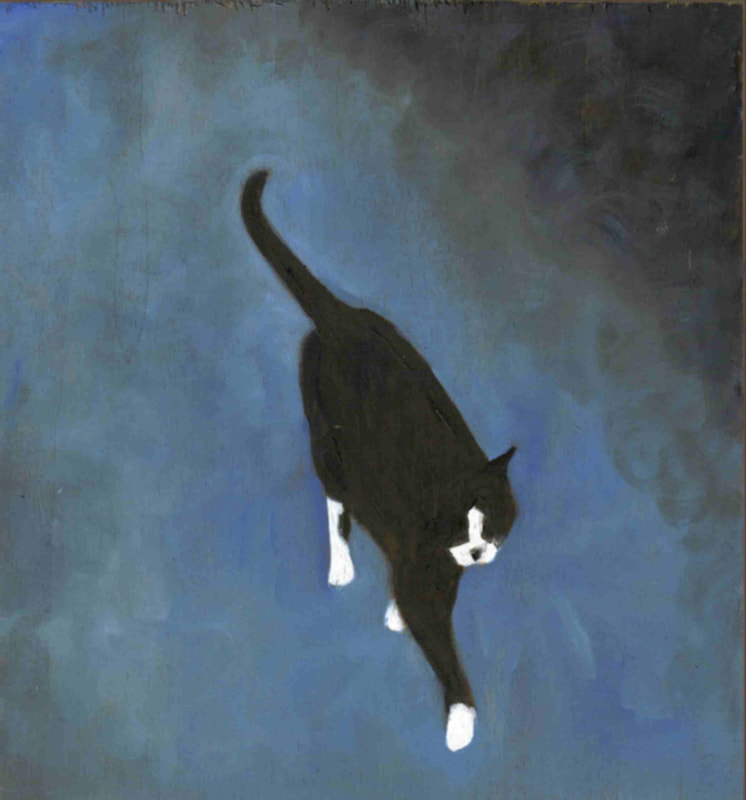

Art by Nancy Bright [https://brightcreationsart.com/}

Art by Nancy Bright [https://brightcreationsart.com/} What I needed was that little teepee of shelter, in a recovery program or with a therapist. I needed help moderating my core trauma response and my outer eagerness to live in the world as a person who had never experienced that winter of the spirit. I needed the support of folks who understood the process of gradual opening to new life. I needed help understanding that a disappointed expectation is not a permanent blight, but a reminder to recalibrate, to understand that deep healing takes time. A day or two of sunshine doth not a spring thaw make. And a warm human interaction does not necessarily signal readiness for full engagement.

Be kind, dear ones. Seasons change, and our psyches have wisdom beyond what we know.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed