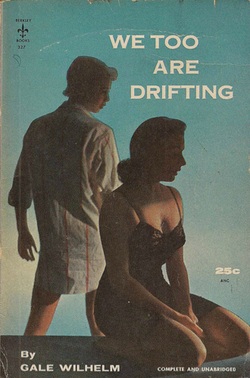

We Too Are Drifting by Gale Wilhelm

Screenplay Adaptation by Carolyn Gage

Gage's adaptation of the lesbian classic by Gale Wilhelm. Originally published in 1935, the novel was republished in the 1950's, and then again in 1984 by Naiad Press. This is an unauthorized adaptation, and rights for the use of it would need to be negotiated with the Wilhelm estate.

Contact Gage for more information.

Jan Morale blazed across the pages of the 1935 bestseller We Too Are Drifting in the tradition of the great American anti-hero. With a caustic cynicism worthy of Catcher in the Rye’s Holden Caulfield, Morale rejected the hypocrisies and pretensions of the Depression era. Like the war-wounded Jake Barnes of The Sun Also Rises, Morale, occupying a similar position outside the arena of heterosexual seduction and conquest, cast a jaundiced eye on the social mores of a post-war generation—the outsider status ironically contributing to the romantic appeal of a tragic loner.

What set We Too Are Drifting apart from other modernist American novels was the gender of its anti-hero: Jan Morale was a woman. What has become almost clichéd in a film world nostalgic for James Dean and Marlon Brando, remains brave new territory for a gender-transgressive protagonist.

The film opens at a bohemian artist’s party in San Francisco in 1932. Influential critics, wealthy patrons, and aspiring artists have come together to celebrate the latest work of the sculptor Kletkin, a great bear of a man whose wife Sparrow is pouring the wine and laughing at her husband’s jokes. This is a gendered world, where women are the hostesses, the models, the trophies for the men who make the art, the money, and the moves.

Amid all the drinking and laughter, the camera picks out the silhouette of what appears to be a slender young man, standing by a window with his back to the party. The camera tracks in on this figure of central stillness, like the eye of a storm, and when the figure turns, the cause of the figure’s isolation is revealed: The young man is a woman; a lesbian.

Her attention is briefly caught by the figure of another solitary woman—until that woman’s fiancé shows up to lay a proprietary arm across her shoulders. Turning from the sight abruptly, Jan makes her way toward the door, ignoring the greetings from those who recognize her as the talented engraver Jan Morale. Kletkin, watching her cross the room, tears himself away from his wife and his well-wishers in order to intercept his protegée. His efforts are not met with success, and he follows Jan out into the street, expressing concern that, in leaving early, she will be missing an important connection with an influential patron.

When Kletkin reaches out to touch Jan, she warns him not to go any further. Reluctantly, he abandons her to the darkness of the night, turning back to the bright lights and warmth of his apartment, where noisy couples are coming and going in a beehive of human activity. Walking into the comfortable obscurity of the fog, Jan lifts her face to the drops that have begun to fall. Relieved to be alone, she closes her eyes in a freeze-frame of ecstasy as she takes the gentle rain on her tongue, and the titles roll...

When Jan arrives back at her garret apartment, she sees a light under the partially opened door: She has a visitor. The visitor is Madeline, a wealthy married woman with an addiction to alcohol and to Jan. She succeeds in seducing Jan, again, who is disgusted by the sordidness of their affair and her own weakness in being unable to end it.

Later the next day, Jan accompanies Madeline to a luncheon party in honor of a lesbian dancer who is in San Francisco on tour. At the luncheon, she meets Victoria Connerly, the woman she saw at the party. Victoria is attracted to Jan, and Jan, agitated with emotion, leaves the lunch abruptly, her hands clenched tightly in her pockets, and a song in her heart.

She remodels her apartment in anticipation of inviting Victoria to see it, and her long period of inactivity ends as she begins work on a new project. Kletkin invites her to model for his next project, a bronze statue of the Greek god Hermaphroditus.

Victoria is the daughter of a middle-class banker and the fiancée of a young attorney. Because of her family’s change of fortunes from the Depression, she has had to leave college, move back home, and take a job as a sales clerk in an antiques store. Taking the ferry over from Berkeley, Victoria meets Jan for bicycle trips to Golden Gate park and picnics in Jan’s apartment. She begins to understand that she is falling in love with Jan, and she acknowledges that, although it is a very strange thing, it feels natural to her. Acting with meticulous restraint, Jan discourages Victoria’s advances, insisting that she go away and consider carefully the consequences of what they have been talking about. If Victoria is really sure that she wants to follow through on her feelings for Jan, Jan invites her to return.

Victoria returns the next day, but when she drinks too much at dinner, Jan, realizing she is not ready, puts her on the ferry back to Berkeley. The two women continue to see each other in a relationship that is filled with nuances and unspoken desires. Finally, Victoria attends a dance at the Mark Anthony Hotel with her fiancé and another couple. The sterility and pretense of her heterosexual relationship has become unbearable to her, and she makes an excuse to flee to Jan’s. Standing at the door of Jan’s apartment, she presents herself for the third time to her lover. This time Jan receives her into her arms, and the two women spend the night together.

Their happiness is short-lived, as Victoria’s plans to spend her vacation with Jan are disrupted by a family trip with the fiancé to Chicago. With sadness, both Jan and Victoria recognize that Victoria is not strong enough to disappoint her family. During this time, news of Kletkin’s death arrives, and Madeline reasserts her presence in Jan’s life.

In the final scene, which follows a frustratingly brief encounter in a strange hotel room, Victoria is leaving on a train for Chicago, flanked by her father and by her boyfriend. A crowd of her girlfriends have come to see her off, and as they are waving and shouting “Good-bye! Good-bye,” Victoria scans the train station, desperate for a glimpse of Jan. Jan, lurking behind a pillar, has turned away from the painful sight of her lover being swallowed up by a world in which women like her must forever appear as monsters and interlopers.

We Too Are Drifting was a best-selling novel in the 1930's, published by Random House at a time when the only market for lesbian manuscripts was in pulp fiction paperbacks. Even more astonishing, the book was reviewed favorably by The New York Herald Tribune, The Nation, The New Republic, and the New York World Telegraph. It was lavishly praised by The Saturday Review of Literature, who reproduced a photograph of the novel’s young author Gale Wilhelm—a photograph in which Wilhelm appears as shingled and tailored as her fictional alter-ego. The book was republished in the 1950's, and in 1984, the Naiad Press, a lesbian publisher, brought it out again.

An American classic, We Too Are Drifting depicts archetypal lesbian characters trapped in a culture that stigmatizes their desire and strips them of dignity. Jan Morale, the hunted and haunted lesbian artist, is one of the most unforgettable characters in literature.

Contact Gage for more information.

Jan Morale blazed across the pages of the 1935 bestseller We Too Are Drifting in the tradition of the great American anti-hero. With a caustic cynicism worthy of Catcher in the Rye’s Holden Caulfield, Morale rejected the hypocrisies and pretensions of the Depression era. Like the war-wounded Jake Barnes of The Sun Also Rises, Morale, occupying a similar position outside the arena of heterosexual seduction and conquest, cast a jaundiced eye on the social mores of a post-war generation—the outsider status ironically contributing to the romantic appeal of a tragic loner.

What set We Too Are Drifting apart from other modernist American novels was the gender of its anti-hero: Jan Morale was a woman. What has become almost clichéd in a film world nostalgic for James Dean and Marlon Brando, remains brave new territory for a gender-transgressive protagonist.

The film opens at a bohemian artist’s party in San Francisco in 1932. Influential critics, wealthy patrons, and aspiring artists have come together to celebrate the latest work of the sculptor Kletkin, a great bear of a man whose wife Sparrow is pouring the wine and laughing at her husband’s jokes. This is a gendered world, where women are the hostesses, the models, the trophies for the men who make the art, the money, and the moves.

Amid all the drinking and laughter, the camera picks out the silhouette of what appears to be a slender young man, standing by a window with his back to the party. The camera tracks in on this figure of central stillness, like the eye of a storm, and when the figure turns, the cause of the figure’s isolation is revealed: The young man is a woman; a lesbian.

Her attention is briefly caught by the figure of another solitary woman—until that woman’s fiancé shows up to lay a proprietary arm across her shoulders. Turning from the sight abruptly, Jan makes her way toward the door, ignoring the greetings from those who recognize her as the talented engraver Jan Morale. Kletkin, watching her cross the room, tears himself away from his wife and his well-wishers in order to intercept his protegée. His efforts are not met with success, and he follows Jan out into the street, expressing concern that, in leaving early, she will be missing an important connection with an influential patron.

When Kletkin reaches out to touch Jan, she warns him not to go any further. Reluctantly, he abandons her to the darkness of the night, turning back to the bright lights and warmth of his apartment, where noisy couples are coming and going in a beehive of human activity. Walking into the comfortable obscurity of the fog, Jan lifts her face to the drops that have begun to fall. Relieved to be alone, she closes her eyes in a freeze-frame of ecstasy as she takes the gentle rain on her tongue, and the titles roll...

When Jan arrives back at her garret apartment, she sees a light under the partially opened door: She has a visitor. The visitor is Madeline, a wealthy married woman with an addiction to alcohol and to Jan. She succeeds in seducing Jan, again, who is disgusted by the sordidness of their affair and her own weakness in being unable to end it.

Later the next day, Jan accompanies Madeline to a luncheon party in honor of a lesbian dancer who is in San Francisco on tour. At the luncheon, she meets Victoria Connerly, the woman she saw at the party. Victoria is attracted to Jan, and Jan, agitated with emotion, leaves the lunch abruptly, her hands clenched tightly in her pockets, and a song in her heart.

She remodels her apartment in anticipation of inviting Victoria to see it, and her long period of inactivity ends as she begins work on a new project. Kletkin invites her to model for his next project, a bronze statue of the Greek god Hermaphroditus.

Victoria is the daughter of a middle-class banker and the fiancée of a young attorney. Because of her family’s change of fortunes from the Depression, she has had to leave college, move back home, and take a job as a sales clerk in an antiques store. Taking the ferry over from Berkeley, Victoria meets Jan for bicycle trips to Golden Gate park and picnics in Jan’s apartment. She begins to understand that she is falling in love with Jan, and she acknowledges that, although it is a very strange thing, it feels natural to her. Acting with meticulous restraint, Jan discourages Victoria’s advances, insisting that she go away and consider carefully the consequences of what they have been talking about. If Victoria is really sure that she wants to follow through on her feelings for Jan, Jan invites her to return.

Victoria returns the next day, but when she drinks too much at dinner, Jan, realizing she is not ready, puts her on the ferry back to Berkeley. The two women continue to see each other in a relationship that is filled with nuances and unspoken desires. Finally, Victoria attends a dance at the Mark Anthony Hotel with her fiancé and another couple. The sterility and pretense of her heterosexual relationship has become unbearable to her, and she makes an excuse to flee to Jan’s. Standing at the door of Jan’s apartment, she presents herself for the third time to her lover. This time Jan receives her into her arms, and the two women spend the night together.

Their happiness is short-lived, as Victoria’s plans to spend her vacation with Jan are disrupted by a family trip with the fiancé to Chicago. With sadness, both Jan and Victoria recognize that Victoria is not strong enough to disappoint her family. During this time, news of Kletkin’s death arrives, and Madeline reasserts her presence in Jan’s life.

In the final scene, which follows a frustratingly brief encounter in a strange hotel room, Victoria is leaving on a train for Chicago, flanked by her father and by her boyfriend. A crowd of her girlfriends have come to see her off, and as they are waving and shouting “Good-bye! Good-bye,” Victoria scans the train station, desperate for a glimpse of Jan. Jan, lurking behind a pillar, has turned away from the painful sight of her lover being swallowed up by a world in which women like her must forever appear as monsters and interlopers.

We Too Are Drifting was a best-selling novel in the 1930's, published by Random House at a time when the only market for lesbian manuscripts was in pulp fiction paperbacks. Even more astonishing, the book was reviewed favorably by The New York Herald Tribune, The Nation, The New Republic, and the New York World Telegraph. It was lavishly praised by The Saturday Review of Literature, who reproduced a photograph of the novel’s young author Gale Wilhelm—a photograph in which Wilhelm appears as shingled and tailored as her fictional alter-ego. The book was republished in the 1950's, and in 1984, the Naiad Press, a lesbian publisher, brought it out again.

An American classic, We Too Are Drifting depicts archetypal lesbian characters trapped in a culture that stigmatizes their desire and strips them of dignity. Jan Morale, the hunted and haunted lesbian artist, is one of the most unforgettable characters in literature.