Adaptor's Notes

By Carolyn Gage

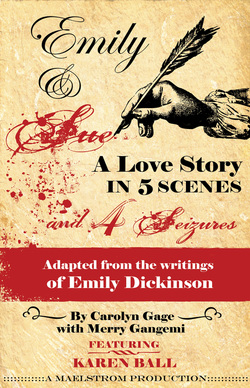

Graphics by Amy Jorgensen

Emily Dickinson has been remembered as a quirky spinster, holed up in a bedroom in her parent’s home and living a life of maidenly rectitude. In fact she had a passionate lesbian attachment with her sister-in-law that spanned four decades. Her poems indicate that her retreat from the world may have been dictated by a disability that was at that time considered a shameful and contagious form of insanity: epilepsy.

Emily’s passion for Susan Huntington Dickinson has been hidden, overlooked, trivialized, misrepresented, and ignored for over a century. As is usually the case with lesbian or bi-sexual artists, the people responsible for preserving their legacy have felt it was their duty to discard or disguise documentation of anything that might be considered scandalous or offensive to the public.

Emily’s first publisher, Mabel Loomis Todd, had an additional motive. She had been the mistress of Austin Dickinson, Emily’s brother and Susan’s husband. Experiencing Susan as her rival and an obstruction to her social ambitions, Mabel harbored bitter enmity toward her. She took pains to erase Sue’s name in the poems, sometimes even changing the pronouns to further disguise the object of Emily’s affection.

The poems have now been restored to their original integrity, and 1998 saw the publication of Open Me Carefully: Emily Dickinson’s Intimate Letters to Susan Huntington Dickinson, edited by Ellen Louise Hart and Martha Nell Smith. For the first time, all of Emily’s existing correspondence with Susan is published, chronologically, with the poems that were written for Susan or sent to her for comment. These documents bear witness to a deep intimacy, with evidence that for some of the poems, Emily solicited artistic and editorial feedback from Susan.

Prior to 1870, epilepsy was considered both hereditary and contagious. Persons with epilepsy were banned from marriage by law in several states, and when they were incarcerated in lunatic asylums, they had their own wards so as not to “infect” the other inmates! Emily was fortunate in that she was born to an upper-middle-class family who could afford her upkeep for life. But, if she had been afflicted with epilepsy, she would have learned as a child that her affliction was a shameful secret that carried a life sentence of isolated seclusion.

Emily & Sue is organized into five sections, which are divided by events that served as watersheds in Emily’s relationship with Susan Gilbert. These are the engagement of Susan and Austin (Emily’s brother), their marriage, Austin’s adultery and the death of Gilbert (Emily’s nephew), and Emily’s death. These turning points are punctuated by seizures that are represented by liminal, auric preludes, blackouts, and then poems descriptive of the physical experience.

Emily’s passion for Susan Huntington Dickinson has been hidden, overlooked, trivialized, misrepresented, and ignored for over a century. As is usually the case with lesbian or bi-sexual artists, the people responsible for preserving their legacy have felt it was their duty to discard or disguise documentation of anything that might be considered scandalous or offensive to the public.

Emily’s first publisher, Mabel Loomis Todd, had an additional motive. She had been the mistress of Austin Dickinson, Emily’s brother and Susan’s husband. Experiencing Susan as her rival and an obstruction to her social ambitions, Mabel harbored bitter enmity toward her. She took pains to erase Sue’s name in the poems, sometimes even changing the pronouns to further disguise the object of Emily’s affection.

The poems have now been restored to their original integrity, and 1998 saw the publication of Open Me Carefully: Emily Dickinson’s Intimate Letters to Susan Huntington Dickinson, edited by Ellen Louise Hart and Martha Nell Smith. For the first time, all of Emily’s existing correspondence with Susan is published, chronologically, with the poems that were written for Susan or sent to her for comment. These documents bear witness to a deep intimacy, with evidence that for some of the poems, Emily solicited artistic and editorial feedback from Susan.

Prior to 1870, epilepsy was considered both hereditary and contagious. Persons with epilepsy were banned from marriage by law in several states, and when they were incarcerated in lunatic asylums, they had their own wards so as not to “infect” the other inmates! Emily was fortunate in that she was born to an upper-middle-class family who could afford her upkeep for life. But, if she had been afflicted with epilepsy, she would have learned as a child that her affliction was a shameful secret that carried a life sentence of isolated seclusion.

Emily & Sue is organized into five sections, which are divided by events that served as watersheds in Emily’s relationship with Susan Gilbert. These are the engagement of Susan and Austin (Emily’s brother), their marriage, Austin’s adultery and the death of Gilbert (Emily’s nephew), and Emily’s death. These turning points are punctuated by seizures that are represented by liminal, auric preludes, blackouts, and then poems descriptive of the physical experience.