Like many lesbians of my generation, public schools have not been especially welcoming or safe spaces for us. I have had my share of negative experiences, including one in which my lesbian theatre company was involved in a “national priority” ACLU lawsuit, because the composer for a musical I produced had been fired from a public school teaching job because of her affiliation with my theatre. This was the late 1980's, and in that state it was still legal to fire gay and lesbian teachers, but here's the catch: This teacher had been fired for merely being associated with a lesbian theatre company... hence the ACLU's interest. They saw it as a legal foot in the door, because it broke Constitutional law. (For a quick refresher on the relevant Bill of Rights clause: “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.”) The case, which was against a school district, a local arts council, and the state arts organization, did eventually settle after an aggressive, state-wide PR campaign. It was a victory of sorts, but my valiant little theatre company had dragged so viciously through the homophobic mud, it was necessary for me to close it and move to another state. (Thank the Goddess, it was before the Internet and viral hate campaigns!)

My island

My island  Ginny

Ginny I was given a doll when I was a very little girl--I believe six, or maybe even younger. Her name was Ginny, and I immediately recognized that she was a queen. She looked something like Glinda from the Wizard of Oz. Ginny was wise, and she was good, and she was very powerful. I was intensely engaged with Ginny and her story, which I was making up as I went along, but which I experienced more as getting to know her.

I would play with the dolls for six to eight hours at a stretch. When most little girls played with dolls, they would change up the outfits or hold miniature tea parties. When Barbie came along about five years later, little girls could put her in her car and drive her to the beach. My idea of playing with the dolls was very, very different. My dolls were engaged in complex plots involving abductions, and magic, and murder, and illicit romance... There were always four or five subplots going on, and the lives of the servants were as intensely dramatic as those of the court. In fact, the heroine of the castle was a rescue doll whose hair had been pulled out and whose body had been vandalized with ink. She was a doll of mystery, greatly favored by Ginny and the Powers that Be. Her name was Pat, and it was only later, as an adult, I realized that the avatar of my youth had been a survivor and a gender-non-conforming lesbian. ,

There was something else I was doing in the dollhouse. I was plotting an escape from reality. My family was not well. My mother was a practicing alcoholic, as was my brother--who, like me, was on the spectrum. My father was a sex/pornography addict with scary and confusing dissociative disorders. I was terrified of him. He was a tyrant, and, from what I experienced as a child, he was never called into account for his malevolence. None of us could ever mount a successful revolution, and any signs of resistance were met with cruelty and sometimes violence. BUT... in the dollhouse, amid all the epic dramas, goodness and innocence would eventually prevail. To that point, the females always won, and matriarchy would always carry the day. Unlike my father, the perpetrators in my stories would be killed, banished, or won over by good. My dollhouse kept my belief in justice alive. It was an alternative world, and, quite frankly, one that I preferred to inhabit... which I manage to do, as much as possible. The dolls were my true family and my dearest friends.

So, anyway… my so-called hyperfocus. My mother had noticed my intense relationship with the dollhouse and with the dolls. Worried that it was going to crowd out everything in my life, she made me pack up the dolls every summer, in the hopes I would go outside and play with the neighborhood kids... you know, "be normal." Yes, I would go outside, but I had an emergency kit of miniature dolls. I would go into the woods with a copy of Peter Pan and enact the entire book down by the creek.

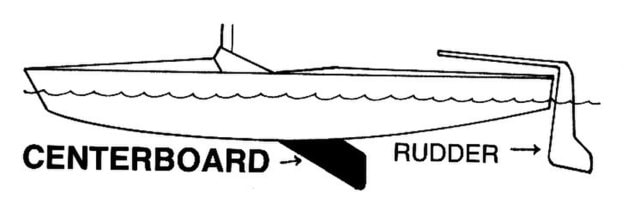

And what do you think happened? Yes, I was lost. It’s like when you pull the centerboard out of sailboat… You can’t set a course anymore. The boat just blows around and very likely will capsize. It’s also like losing your compass. There’s no more “north” anymore. All directions are the same and equally meaningless. No centerboard and no compass, I wandered and I also went whichever way the wind blew. I copied my friends. I tried to please other people. My mother wanted me to get married, so when I was eighteen I got engaged, and three months after I turned nineteen, I walked down the aisle. I had no idea who I was or what I wanted to do with my life. But, never mind. It didn't matter. There had been this massacre of the imagination. My entire tribe had been wiped out.

Me as "Fly Rod" Crosby

Me as "Fly Rod" Crosby So, at thirty, I was back in the dollhouse. Back making up stories and bringing characters to life. I was an actor and a director, and for a little while I taught theatre classes, but eventually, I found that my true calling was being a playwright.... which was what I had been doing in the dollhouse. And I have now been a professional playwright for more than forty years. I have written over a hundred plays that are published in nine collections of my work. I have toured all over the US, and some in Canada, and in Europe, and I have met a whole lot of really wonderful and interesting people. I have had a great life. Full of challenges, but always rich in meaning.

The moral of the story is my mother didn’t need to worry about me. My special interest was going to give me a life... the life I was meant to have. It wasn’t the life she had planned for me, but it was the one I wanted.

Beatrix Farrand, genius

Beatrix Farrand, genius  Reef Point perfection

Reef Point perfection  Reef Point... the "ground"

Reef Point... the "ground" So my mother had a plan for me, but she didn't take into account what my ground was. Or maybe she did, and she thought if she packed up all the dolls and ripped apart the plywood of the dollhouse—if she bulldozed who I was—then her plan would work. And I guess it did... for a while. I was married for a year. And then I just went drifting. But eventually, after seventeen years, I began to evolve a plan, or a series of plans, that would fit the ground of who I was, an autistic person with a definite special interest.

Why am I telling you this? Because lots of people throughout your life will have plans for you. Your parents... and that's not necessarily a bad thing. They love you, and it's natural for them to have some idea of how they think your life should be. Your teachers, your friends, your partners... they may all have vague or definite plans for you. But sometimes--most times--they don't really see the ground of who you are. Or they see it, but they don't "get it." They think the trees block the view, and the rocks are hard to mow around. Your ground won't work with the plan they have in mind. But your job is to understand your ground: what is you and what isn't you, what probably isn't going to change, what you love, what makes you the happiest in the world. And no matter how weird that is, if it's your special interest, you can probably make a great life out of it.

Why? Because you will do that thing long after everyone else has clocked out and gone home. You will do it on weekends. You will do it on holidays. You will do it for low pay or no pay. And in time, you will probably stand out, because you will be working harder, smarter, better than everyone else, because of that so-called "hyperfocus." You may not see the plan now, but trust the passion. It's a gift. These are the years you should be learning your ground, appreciating it, standing up for the beauty of it and your right to inhabit it.

So, if you take away anything from what I've said today, I hope it's this: t

“Fit the plan to the ground, not the other way around.”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed