I recently ordered a play. I rarely do that. But this was the first play written by a woman to be produced on the main stage at the Royal National Theatre. Furthermore, it was a play about women's history... the Suffrage Movement in England, to be exact. And... it dealt with a lesbian love story! It garnered four-star reviews in most of the London papers, and even managed three in The Times.

Needless to say, I was intrigued.

I've been writing plays about women's history featuring lesbian love stories for a quarter century. Not coincidentally, I have also been writing about the censorship of lesbian and feminist drama for that long. Had there been some kind of cultural revolution in the West End that I had missed? Or was there something about the play itself? I had to find out.

Emily Wilding Davison

Emily Wilding Davison 1) The title: Her Naked Skin. Whew... Thank the Goddess she had enough sense to give it a title that showed some skin! And how clever of her! Like the woman who shows a little cleavage in the board room... All one has to do is think of the titles of Suffrage books to realize the strategic brilliance of Ms. Lenkiewicz' title. Just imagine a West End play with a title like "Shoulder to Shoulder," or "Women Who Dare," or "The Fighting Days..."

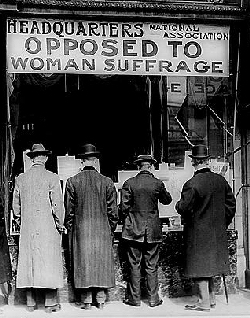

Davison Being Trampled

Davison Being Trampled 2) It opens with a woman's apparent suicide. Well, actually, that's controversial. It's a rather celebrated death, actually. Emily Wilding Davison was a militant Suffragist. She had been a hunger striker in Holloway. She had planted a bomb in the Prime Minister's home. She had also taken extraordinary measures to follow a course of study at Oxford at a time when Oxford did not grant degrees to women. This, of course, allowed her to be a governess... which is something like a glorified nanny.

Davison's apparent suicide was occasioned by her running out onto the track with a Suffrage banner just as the King's horse was rounding the bend. She was trampled to death. Some think she intended to die. Personally, I think she planned to attach the banner to the ass of the King's horse and make him advertise her cause. She died with a return rail ticket and a ticket to a women's dance in her pocket. I think she was planning to celebrate. On the other hand, she had intentionally thrown herself thirty feet down an iron staircase in Holloway.

Her Naked Skin opens with Emily in front of a mirror. How reassuringly female! Because even Suffragists on their way to their death care about their looks! The gramophone gets stuck... Emily does not fix it immediately. A metaphor for the broken-record quality of women's demands for equality? The annoying redundancy of our political movements? And then the script calls for a projection of the authentic, grainy, nearly indecipherable, 1913 newsreel footage of her death. The playwright acknowledges in the stage directions the obscurity of the imagery, but notes that "the general impression of the film is that something has 'happened.'"

Brilliant.

Photo for University of Bristol Production

Photo for University of Bristol Production 3) There is a lesbian love story: An upper-class, married Suffragist meets and falls in love with a fellow Suffragist, a factory worker, in prison. There is a scene that calls for their semi-nudity in bed. I'm assuming the naked half would mean their breasts exposed. This is always good for box office. I know because I am a producer sometimes. When word gets 'round that there are bare titties in a show, there is a certain demographic who would otherwise never set foot in a women's theatre. Again, a good move. And, of course, with a title like Her Naked Skin... well, what choice did she have?

B & D at the RNT

B & D at the RNT 5) The lesbians break up. The factory worker is jealous about the fact that her lover has had other affairs (with men) before meeting her. Doesn't make sense to me either, but then, the factory worker also keeps going on about wishing she could have been a virgin. The only thing I can guess is that virginity and monogamy, being obsessions for heterosexual men, were introduced to help them identify with the characters. The fact is this: Lesbian audiences are never going to fill the National. Straight men and their girlfriends and wives will. If the playwright plays her cards right.

Nothing like those bandaged wrists to bring back a lover...

Nothing like those bandaged wrists to bring back a lover... 7) The working-class lesbian marries unhappily. Her punishment for surviving the wrist-slitting.

8) The upper-class lesbian has an Ibsenian ending, walking out on her husband and her seven (7!) children. Oh... but she stops and checks herself in a mirror on the way out. Get it? The way Emily did at the top of the show, on the way to her suicide/death? Women and mirrors... the bookends for the action. Revolution is what happens to us between primping.

And that, my friends, is how it's done. That is how to get your women's history/lesbian play into a first-class theatre with good reviews.

Excuse me. I think I'll go back to my failures... Which you can check out at www.carolyngage.com.

See also: "How I Came To Write A Play Where the Lesbian Doesn't Kill Herself."

RSS Feed

RSS Feed