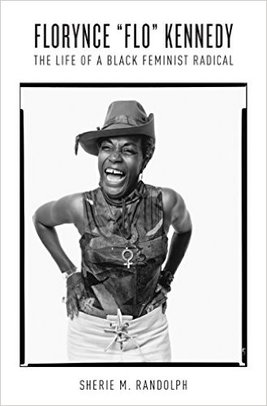

Yes! Finally! A biography about this amazing woman!

Yes! Finally! A biography about this amazing woman! “All oppressed people have a right to violence. It’s like the right to pee: you’ve gotta have the right place, you’ve gotta have the right time, you’ve gotta have the appropriate situation. And believe me, this is the appropriate situation.”

And Florynce would know. She had organized a "pee-in" at Harvard University to protest the lack of women’s bathrooms.

Valerie Solanas arrested.

Valerie Solanas arrested. Florynce would step up as legal advisor to Valerie Solanas after her attempted assassination of Andy Warhol in 1968. Solanas was insisting on conducting her own defense, and the first order of business was to prove to the courts that her mentee was not crazy. This required a writ of habeas corpus, because Solanas had been taken to a psychiatric hospital.

She was also an attorney involved with the landmark Abramowicz vs. Lefkowitz case, arguing for women’s right to safe abortions. This was the first case where women who had been victimized by illegal abortionists were called to testify. Prior to this, it had only been physicians, and this trial established valuable precedent for the later Roe V. Wade case. Florynce went on to publish a collection of some of this testimony, titling it Abortion Rap.

Florynce not only called out the National Organization for Women for their failure to stand with Valerie Solanas in her trial, but she would also call out the Black Power movement for its opposition to abortion rights, at a time when the male leadership was framing it as a genocidal conspiracy against women of color.

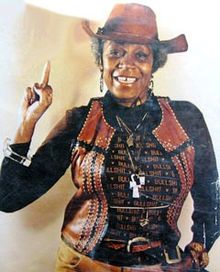

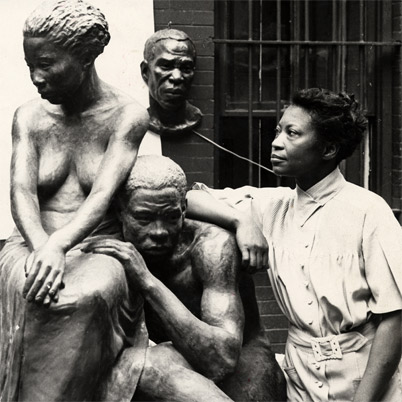

Flo at a 1972 N.O.W. march.

Flo at a 1972 N.O.W. march. Author and tireless researcher Sherie M. Randolph gives us the key to solving this conundrum. In a word: intersectionality. Yeah, that thing that was supposed to have been absent from the 1960's. Well, Flo Kennedy was the Empress of Intersectionality, and, for that, she paid a price.

In an era where the media was identifying Women’s Liberation as a white women’s movement, and Black Power as an African American men’s movement, Kennedy was busy calling out the former on their racism and the latter on their sexism. She was dragging feminists from the National Organization for Women to Black Power conferences that specifically banned whites. She was arranging with a Black-owned resort in Atlantic City for housing and meals for the predominantly white protestors at the legendary 1968 Miss America Pageant.

Single-issue organizing was difficult enough, but Florynce wanted everyone to see the connections between the many oppressions and to follow her example in showing up for them all. As a result, historians found it easier to focus on less intersectional--and less controversial leaders. This reductive approach to history has led to the erasure of the anti-racist work of early feminists and the anti-misogynist work in the early Black Freedom Movement... and the erasure of Florynce Kennedy.

Interestingly, she also served as a defense attorney for Jerry Ray, the brother of James Earl Ray, convicted for the murder of Dr. Martin Luther King. He was before a Senate sub-committee, and Florynce used the occasion to place the government on trial for conspiracy. Jerry had been accused of robbing a bank with his brother, in order to explain the large sums of money that had funded James’ elaborate escape. In the end, the committee decided that James Earl Ray could not have acted alone, but they rejected any theory of government involvement. (“What a beautiful shade of red...?”)

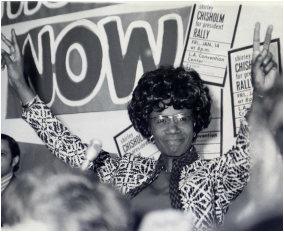

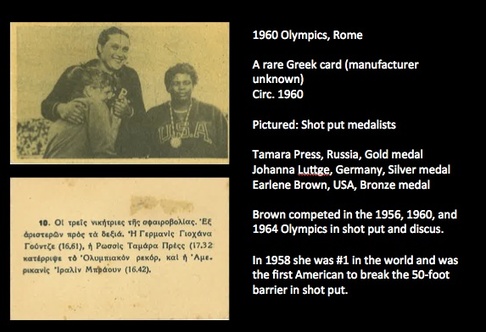

Shirley Chisholm running for President.

Shirley Chisholm running for President. We owe a debt of gratitude to Kennedy's biographer, Sherie M. Randolph. She spent fifteen years researching her subject. Florynce had written her own "autobiography," Color Me Flo: My Hard Times and Good Life, but it is less a biography and more a collection of speeches and interviews, with photographs and copies of leaflets. The papers she had donated to the Schlesinger were filled with gaps and omissions. Sherie found that Florynce's sisters had their own collections, but these were also incomplete. It is important to remember that Kennedy had been under FBI surveillance through many of her years of activism, and that, after her death, friends and colleagues had removed and destroyed papers that they felt might have jeopardized the safety of other activists. Florynce's biographer has performed a Herculean feat in assembling the details of her subject's life and causes. And now, finally, the errant papers are all at the Schlesinger, along with an extensive collection of video. And there is, at long last, a biography.

Florynce Kennedy’s life is a inspiration for the timid activist. She never hesitated to say the thing that was on her mind, no matter how disruptive or how unpopular it was. She was never afraid to call out her own movements. She was not intimidated by accusations that she was being "divisive," that kiss-of-death word used so effectively to silence in-house dissent. To her critics, she would say, “Unity in a movement situation is overrated. If you were the Establishment, which would you rather see coming in the door, five hundred mice or one lion?”

Oh, the lion, by all means. Give us the lion.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed