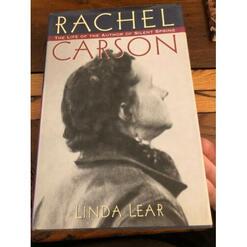

My review had been centered on the biography's failure to apply the word lesbian to any of the intimate and well-documented relationships that Carson had with women throughout her life. Because I thought these relationships would be of interest to my readers, I am republishing this review:

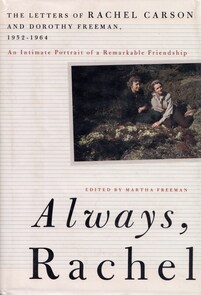

This omission is peculiar in light of the fact that the author, Linda Lear, had access to the correspondence between Rachel Carson and Dorothy Freeman --- a correspondence that documents the two women's lesbian passion and commitment during the last ten years of Carson's life. In fact, three years ago, a collection of the letters was published in Always, Rachel: The Letters of Rachel Carson and Dorothy Freeman, 1952--1964.

Dorothy Freeman, Rachel's intimate partner for the last decade of her life.

Dorothy Freeman, Rachel's intimate partner for the last decade of her life. Carson, author of the ground-breaking exposé of the risks of pesticides, Silent Spring, is remembered now as the founder of the ecology movement, but she might also be considered the first ecofeminist. Through the network of connections she made with women during her lifetime, she evolved her philosophy of the interconnectedness of all forms of life. Because of the censorship she imposed on herself, a censorship that her biographers have perpetuated, the significance of Carson's world of female relationships has not been explored for its impact on her career and on her writing.

Eleanor Roosevelt and her lover Lorena Hickok

Eleanor Roosevelt and her lover Lorena Hickok Lear's predicament is not unique. In fact, it parallels the situation of Lorena Hickok's biographer, Doris Faber, who insisted that the romantic language in the Hickok-Roosevelt correspondence "does not mean what it appears to mean." Fortunately, her homophobic treatment of Hickok has been countered in recent years by Blanche Wiesen Cook's biography of Eleanor Roosevelt and by the publication of Empty Without You: The Intimate Letters of Eleanor Roosevelt and Lorena Hickok. Similarly, the publication in 1998 of Open Me Carefully: Emily Dickinson's Intimate Letters to Susan Huntington Dickinson, poses a serious challenge to the assumptions of previous biographers about Dickinson's heterosexuality. One irate male academic has characterized the publication of these letters as "an utter distraction from her outstanding intellect and her talent."

Emily Dickinson and her lover Sue Gilbert

Emily Dickinson and her lover Sue Gilbert In addition, what appears to be "reasonable doubt" in the minds of biographers like Lear and Faber reads like homophobic panic and denial to scholars who find it unreasonable to explain away an obvious constellation of lesbian or gay relationships on a case-by-case, or even word-by-word, basis.

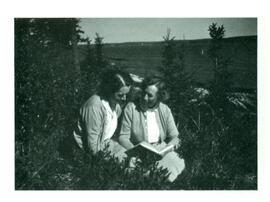

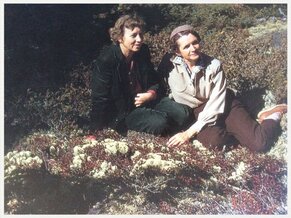

Rachel and Dorothy

Rachel and Dorothy "... I have been remembering that my very first message to you was a Christmas greeting. Christmas, 1952. I knew then that the letter to which it replied was something special, that stood out from the flood of other mail, but I don't pretend I had any idea of its tremendous importance in my life. I didn't know then that you would claim my heart --- that I would freely give you a lifetime's love and devotion. I had at least some idea of that when Christmas came again, in 1953. Now I know, and you know. And as I have given, I have received --- the most precious of all gifts. Thank you darling, with all my heart." (pp. 66-67, Always, Rachel)

Or the words of Dorothy Freeman:

"How sweet to find your clothes mixed in with mine, dear --- that brought you near. I've wanted you so when I looked at the moon, when the tide was high; when the water made wild sounds in the night; when we went tide-pooling; when the anemones were exposed for a few seconds as the water rushed away from the cave; but most of all, darling, when I went back to the veeries ---" (p. 117, Always, Rachel)

Rachel and Dorothy

Rachel and Dorothy "New York --- darling --- a week from this moment I shall be with you if all goes well -- and it must! Yes, I think we can be casual if we meet at the desk --- just a chilly glance I'll give you and say, 'Glad you made it...'" (p. 69, Always, Rachel)

What is to made of the humor in this note, if the subtext is not lesbian?

In the early years, the correspondence itself was carried on in a clandestine fashion, with each woman writing a letter to the other woman's family, "for publication," with the private love letter hidden surreptitiously inside.

In the case of Carson and Freeman, it is not even necessary to resort to Lilian Faderman's argument for the inclusion of non-genital love relationships in the category "lesbian." In light of the women's own writings, it is unreasonable to conclude that the relationship was platonic. One does not need to disguise a platonic same-sex relationship from the desk clerk at a hotel!

Mary Scott Skinker

Mary Scott Skinker Mary Scott Skinker, 36, was a professor of biology at the Pennsylvania College for Women, where Carson was studying to become a writer. Under Skinker's mentorship, Carson began to focus her creative energies on biology. Carson's correspondence to friends at this time indicate that she was deeply infatuated with her teacher. When Skinker took a leave-of-absence to attend Johns Hopkins University, Carson attempted to follow her, but was unable to raise tuition money. Instead, she founded a science club she named Mu Sigma Sigma --- Miss Skinker's initials in Greek. After graduation, Carson rendezvoused with her former professor in Skinker's family cabin in the Shenandoah Valley. As Lear coyly notes, "There were no longer any boundaries between mentor and protégée." (pp.56-57) (Shades of Radclyffe Hall's "... and that night they were not divided"!) Skinker and Carson maintained contact with each other for two decades, and when Skinker, 57, became hospitalized with cancer, she gave Carson's name as the person to be contacted. It was Carson who stayed with her until she lost alertness, and only then was her care taken over by members of her family.

Rachel and Marie Rodell

Rachel and Marie Rodell Because of her failure to provide a lesbian context for Carson's experiences, the reader must read between the homophobically elided lines to understand her relationship to Marjorie Spock and Mary Richards. These two socially-prominent, single women had bought a house and were living together. We are told that they became members of Carson's inner circle of friends.

Marjorie Spock

Marjorie Spock This was a lawsuit sparked by one woman's desire to protect her disabled life-partner. Carson, whose first love had been mercilessly harassed out of her career as a college professor and later out of a career in the government, was again faced with a situation where the survival of a lesbian she loved was being threatened. This time Carson was in a position to do something.

What did the Spock-Richards relationship mean to Carson, who was still living with her mother --- who had never been able to live openly with the women she loved? How did the passionate crusade of a woman devoted to protecting her partner affect Carson's own interest in the issue of pesticides? Did the security and nurturing she received from the maternal Dorothy Freeman influence her decision to write a book that she knew would raise a fire-storm of controversy? How did the persecution of Skinker influence Carson's own career decisions, as well as her decisions to live a deeply closeted life? Did her oppression as a woman in a male-dominated field and as a lesbian in a heterosexual world influence her advocacy for respect for the diversity of life on the planet?

RSS Feed

RSS Feed