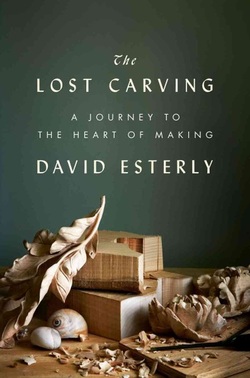

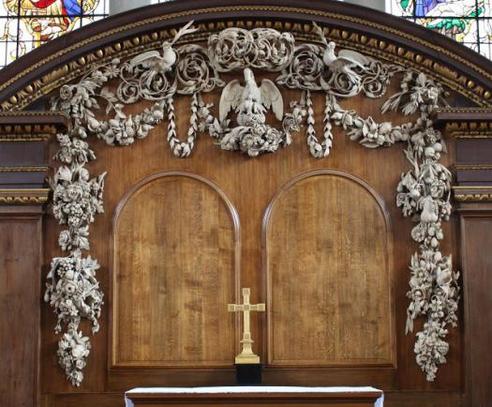

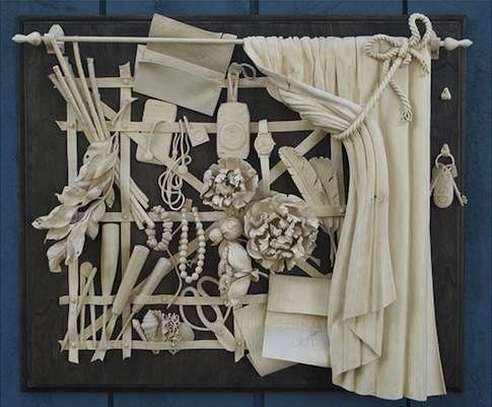

I just finished a wonderful book, The Lost Carving by David Esterly. The author is a woodcarver who specializes in ornamental fruits and flowers. He was commissioned to replace some remarkable work by eighteenth-century carver Grinling Gibbons that was destroyed in a fire at Hampton Court. The author takes us on a saunter into another era, without losing sight of the contemporary political skirmishes surrounding British heritage restoration work (being done by an American!)… along with meditations on the art of woodcarving, as well as bucolic commentary on the seasons in his rural workshop.

But the reason why I am writing about David Esterly’s book is that it set me to thinking about my own craft. The subtitle is “A Journey to the Heart of Making,” and I found myself applying many of his observations to my own work as a playwright.

In my playwriting, that propulsion is always the personal compulsion to tell a story that in some way answers a need of my own: the reclamation of the history of my lesbian foremothers that I so desperately need, the validation of other incest survivors who bear witness, the heroines who have dared to challenge the patriarchy. What is it that checks this evangelical or propagandistic momentum? The rigid format required for telling a good story on the stage. The scenes that open and close the acts, the building of suspense and momentum, the deft handling of exposition (a major challenge with historical material), the subplots, the comic relief, and so on. And out of that tension, enhanced focus, economy of dialogue… precision.

Esterly discovered something else. That there is third dynamic in play: The heel of the restraining hand must rest on a stable surface. Ah ha. The audience. The audience grounds the passion of the artist and the cleverness of the craftswoman. Always the audience. What do they see? How long can they sit? Can they tolerate a shock or will it alienate them? What are the limits of their “suspension of disbelief.” In the words of Esterly, “It’s a beginner’s error that you can operate while floating above the world, in some ether of strength and desire and inspiration.” In fact, I may be mistaken about the audience being the grounding. Perhaps, for the playwright, the heel of our metaphorical hand rests, for better or worse, on box office revenue.

And along similar lines: “If the viewer is truly deceived, then the effect of the art object is no different from that of the actual object.” He was talking about painting wood carvings to simulate the real thing. And then he goes on to describe something called the “valley effect.” A Japanese scientist found that the closer he designed robots to resemble humans, the more repellent people found them. (The “valley” is the dip in acceptance levels.) Esterly notes, “Simulacra are disturbing. We want to know where we stand with a thing. We want the terms to be clear.”

And I feel the same way about sex in the theatre. If the actors are going at it, the audience becomes curious about how they deal with it every night. If the actress is taking all her clothing off, the audience again leaves the world of the play to speculate about the performer and her boundaries. Is she dissociating? Has the production resulted in her being stalked? Is she cold? Simulacra are disturbing. And, as Esterly notes, “We want reassuring differences.” In film, these are not necessary, because we are looking at dots on a screen, projections of a thing that happened often a long time ago and in another location. Not so for live theatre. We need those reassuring differences.

The structural weakness of theatre as a medium? The platform, the one-hundred-and-twenty minutes. The need for a break after sixty minutes. These are the fragile stems upon which the playwright hopes to hang her weighty themes and life-changing drama. And she does it by exquisite compression, in both time and space. She has a captive audience, as opposed to a novelist or even, these days, a viewer of film, who can rent the DVD at home. Those audiences can set the book down or hit pause if they need a bathroom break. The playwright has to respect the captive nature of her audience. She has to work to hold interest and be responsive to the needs. The break must either be comic relief, or an intermission. The structural weakness of theatre produces the formal opulence of compelling dramatic content and masterful storytelling.

David Esterly

David Esterly Esterly made the discovery that fifty percent of the effort will achieve ninety percent of the effect. I immediately thought of all the amateur actors I had known who would learn their lines a few days before the performance, of the tech weeks where the sets, costumes, and lights come together for the first time on opening night. But Esterly goes on to observe, “If you allow yourself to stop at that ninety percent, then the carving can never succeed, never really succeed.” And there it is. Why I love Chekhov. Why I always choose Chekhov when coaching an audition piece. Chekhovian dialogue is always the tip of the iceberg, and if the actor has not studied the nonverbal submerged aspects of the character, the words are unactable. In other words, there is no ninety percent with Chekhov. The silences, the shadows, the thoughts—self-censored by the character—should scream across the footlights.

But here’s the rub: It takes another fifty percent to achieve that final ten percent. It may not be missed by the masses. Certainly, not by folks who are paying for your time. I have worked with many an actor who balked at doubling their effort for such a diminished return, failing to recognize that, in the words of Esterly, that last ten percent is “everything.”

I think of film. On location. Jump cuts, narration, voice-over, multiple camera angles, the opportunity to edit, close-ups, green screens, computer-generated imagery (CGI). Live theatre cannot hope to compete with the special effects or the realism of film… or the control over final product that an editor wields. Why does theatre spend so much money on a lighting system that can accommodate thousands of light cues, or sets that are sumptuously fanciful or meticulously realistic? These were trends that reached their apotheosis at the turn of the century, just before film began to poach our audiences. As film advances, why didn’t theatre head for our “redoubt of mountain fastness”… the thing that film can never replicate. The immediacy, the contemporaneity of real flesh-and-blood enactment before one’s very eyes. The stage performer’s skillset should be very different from that of a film actor. The stage performer must establish a rapport with an audience, a real relationship in real time and space.

Theatrical speeches, those verbal arias building in argument and intensity, used to carry audiences into such raptures they would halt the play for multiple rounds of ovations. Today, producers consider this kind of writing an embarrassment, a mark of amateurism. The playscript is expected to ape the screenplay, with dialogue consisting of one or two lines. This is like hiring a woodcarver to imitate work done by CAD/CAM. I have never understood why, except that film costs more and usually makes more money than live theatre, and on this basis alone, the presumption is made that it should be the touchstone for all the performing arts. Film is a visual medium, where stage is aural. Film is cool; live theatre smokin’ hot. If theatre is becoming obsolete in the age of electronic media, we have no one to blame but ourselves.

“A carver begins as a god and ends as a slave.” Or, as Esterly explicates, the balance of power progressively shifts from the maker to the made. “You start as a godlike creator, imposing ideas on a passive medium, and you end up grounded in the life of this world, taking instructions from the thing in front of you.”

A good play is about something, and a great play is about something significant… and the great playwrights choose to write about significant issues that are on their own edge. In other words, the higher the stakes for the playwright, the more she is incentivized to go for that extra ten percent. Starting out with a lofty thesis, the playwright is quickly brought down to earth by the constraints of the physical stage and performing within a two-hour span. As the play develops, the characters themselves begin to dictate their own dialogue. Then there is the need for scene sequences that will allow audiences the time to assimilate the emotions from the previous scene. The further along into the process, the fewer the options. Eventually, for me, the process of invention has turned into one of discovery… petition even. Will this work? Will the characters accept this? Can an audience go along with that? Can this be staged… and within a budget?

Esterly, who expected that his replication work would be haunted by the ghost of Grinling Gibbon, found that he was merely a fellow traveler: “The objects were telling me what they’d told him. They were defining the possibilities of their modeling.” Esterly began to question who was in charge, and his answer emerged as he worked: “an embryonic carving intent on being born.” In other words, what he was making had begun to participate in its making.

This is as apt a description of playwriting as I have ever read. A play may appear to be the brainchild of the writer that is then painstakingly brought to life through the collaborative effort of dozens of artists. But my experience is more aligned with that of the sculptor Rodin who said, “I choose a block of marble and chop off whatever I don’t need.” There is an idea… story, or theme, or character—or a combination of the three. I begin to chip away the obviously extraneous elements, and as I do this the work begins to define possibilities for me. The godlike imposing of my vision on the medium begins to morph slowly into a listening-and-response. There is an embryonic drama intent on being born.

Because Esterly was attempting to recreate the work of another sculptor, he felt a kinship with the carvers in Gibbons’ workshop. Were they fabricators for a conceptualist? Looking at the finished work, he concluded, “They seem to have carved as if it were their own composition. Sincerity shines out from the work, sincerity that seems inseparable from skill.” Sincerity inseparable from skill. In this commodified world, who would make that connection? “The daunting technical demands of the work appear only to have deepened their engagement. Its difficulty was their honor.”

Working for three decades as a lesbian playwright in a culture where lesbians neither own theatres nor have a historical affinity for them, I recognize the truth of Esterly’s insight into the craftspeople who worked for Gibbons. The demands of telling a lesbian and feminist story in such a labor-intensive and transitory medium, which has historically been profoundly hostile to women of non-traditional appearance and resistance to female gender roles, have been daunting. And those daunting demands did deepen my engagement. The difficulty drove me to write a book on how to produce and direct lesbian theatre, as well as publish a collection of scenes and monologues with lesbian content. And then there are the sixty-five plays in seven collections... all self-published. The difficulty of the work is my challenge, and when I take it up, it does become my honor.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed