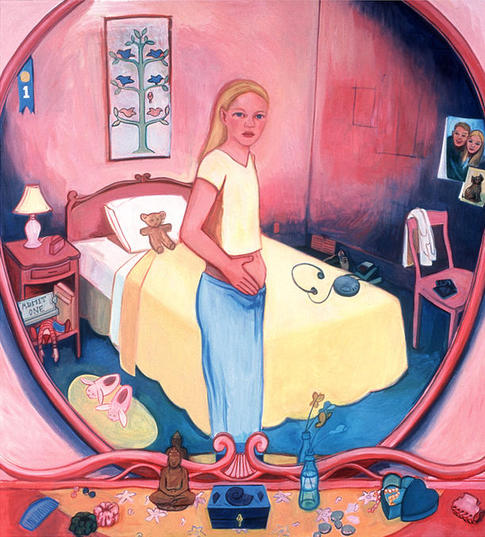

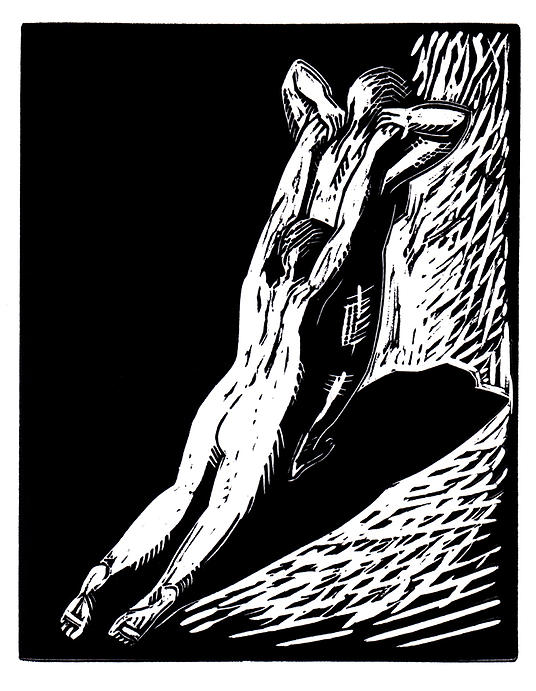

"Showing" from the Family Secrets series

"Showing" from the Family Secrets series For me, as a lesbian, the silences between a couple are especially poignant. Nothing personifies the power of this silence better than Dodds’ painting “Dressing.” In this painting, there is an inter-racial couple who appear to be dressing up for an evening. In other words, getting ready to show off their coupledom in public. The white woman, still in her slip, is helping her partner on with her dress. The painting has a stillness for me that feels as if the moment has been frozen in amber. Now, perhaps this is a projection on my part, but when I look at this picture, I feel that there is a nearly unbearable tension between the women, a tension arising from what cannot be spoken. I look at the picture and I wonder if there is infidelity, or just boredom. Or has the racism and patriarchal values of the outside world become internalized, undermining and overwhelming their attempts to be intimate? All of the above… or none?

In these drawings there is a young woman and a child, or perhaps the child was the young woman. The visit triggers a trip to the basement, and then we meet the “Bound Child.” This is followed by the presence of a benign female guardian who watches by the bed. And then we see the young woman waiting up… and the loop of drawings circles back to the visit. Again, it may be the playwright in me, but I find story in this series. It’s a repeating story, the story of recovery. The sudden glimpse or intuition (aka “the visit”), which sets off the search for one’s own secrets, which leads to discovery of abuse/trauma. This discovery reveals the what was missing: the guardian. Or maybe, it leads to the correction of this absence. The arrival of the guardian lays the foundation of security which can open the survivor to the possibility of that initiating impulse personified in the visit. Rinse and repeat. This is my life. And someone, miraculously has drawn it.

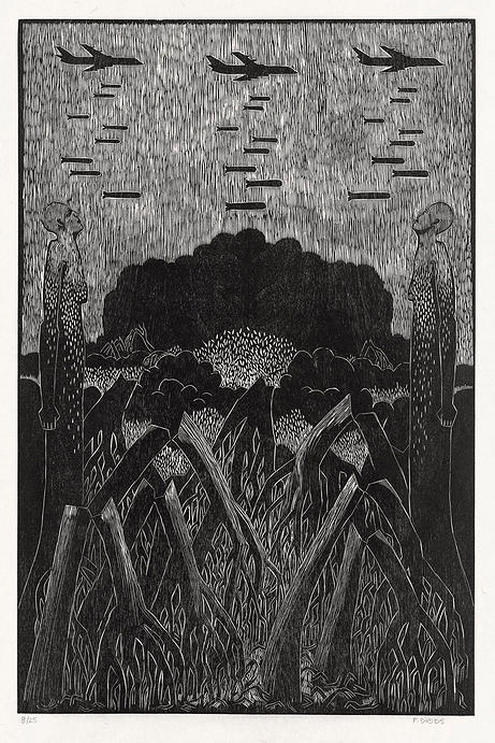

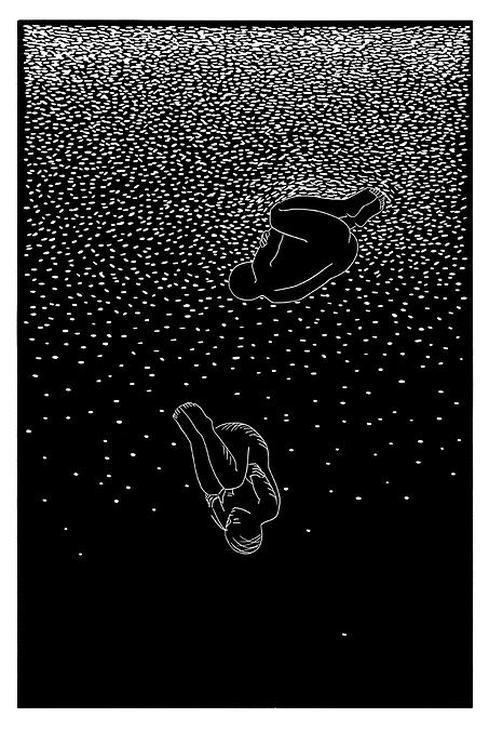

"Memory's Witness"

"Memory's Witness"

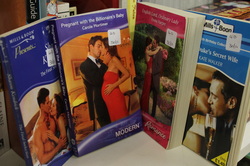

Dodds has also done two book projects. As a writer, I found both of these fascinating. They brought to mind the words of author and activist Toni Cade Bambara: “I’m trying to break words open and get at the bones, deal with the symbols as if they were atoms. I’m trying to figure out not only how a word gains its meaning, but how it gains its power.”

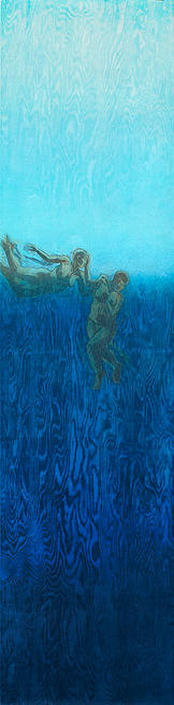

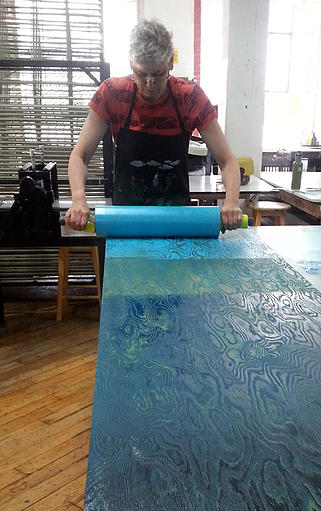

The first book project is titled "Language for a Faltering Mind." The project was inspired by Dodds’ residency in Catalonia. In her words:

“As I grappled with the meanings of words, their nuance, their references, I was impressed with the power and political weight of language, and the significance of language as a touchstone of identity for the Catalonian people… In my contemplative walks, I happened upon the naturally formed bark fragments that fall from the trunk of the Plane (Platan) tree, ubiquitous in Spain. These unique forms struck me as hardly different from the letterforms that we collect and arrange into words to create meanings – meanings that can only be understood if one has the key of comprehension. I gathered, inked and printed these natural shapes, combining them in the manner of a potentially comprehensible language, as booklets and charts.”

“Coming home, I observe an aging relative who is losing her grasp of the English language, the only language she knows; and with it, the specificity of her relationships and human connections… Visiting her with notebook in hand, I gathered her utterances as I had the fragments of tree bark. I printed quotations of her collected words, and paired each one with a composition of printed bark fragments. The combination of the printed text with the printed tree bark, each with their spacings and layerings whether of meaning or form, represents for me, an alternative linguistic exchange, a continuing dialogue.”

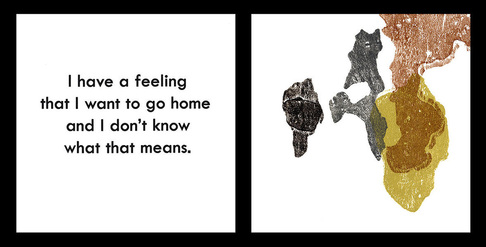

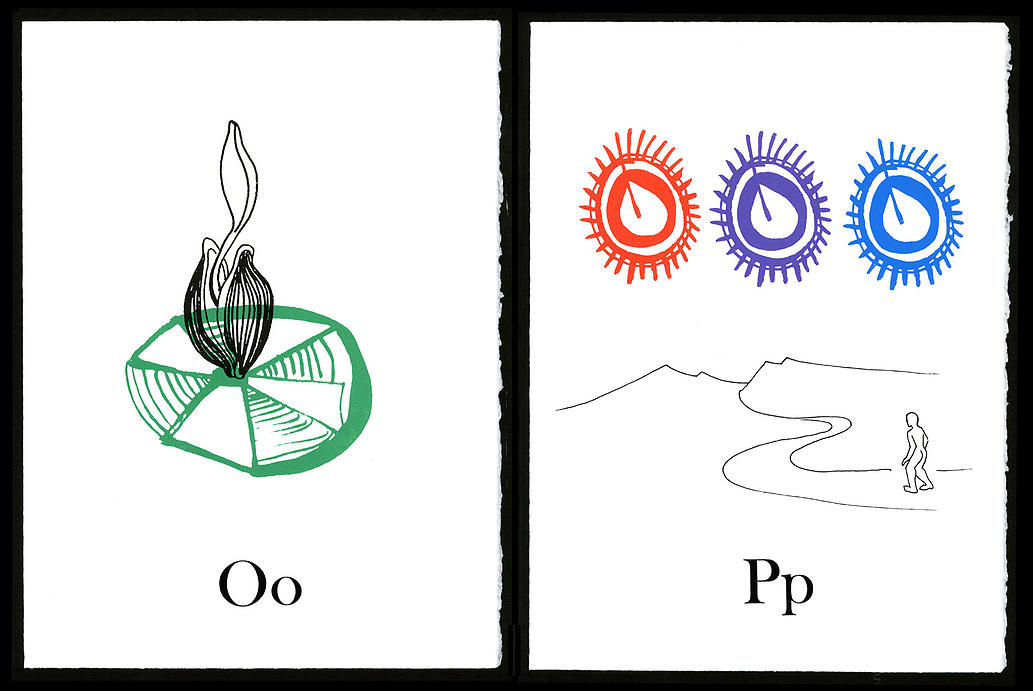

"I Have a Feeling That I Want to Go Home"

"I Have a Feeling That I Want to Go Home" "Each letter is represented by a French and English word of same or similar meaning. Diane and I wanted to make imagery about experience, ideas, and perspectives, so we chose nouns for concepts, qualities, and states of being - not things. To create the work, we each separately drew images in response to the chosen words in a spontaneous, stream-of-consciousness manner and later combined the images through serigraphy... The result is a single, layered, complex image to represent each word.

I have a special appreciation for her work that deals with relationships between women. It reminds of the words of the lesbian poet Adrienne Rich:

“The connections between and among women are the most feared, the most problematic, and the most potentially transforming force on the planet.”

Please visit Pamela Dodds' website, to see more of her art.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed