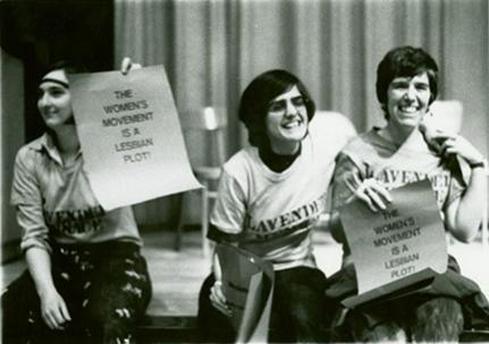

Marriage resistance was a “thing” in three districts of the Pearl River Delta from the mid-nineteenth century through the 1930’s. In fact, anthropologists have had the temerity to call it a movement. At its height there were an estimated one hundred thousand women refusing to allow men access to their domestic and sexual services through the institution of marriage. They were referred to as the sworn sisters of the Golden Orchid.

Pearl River Delta

Pearl River Delta Girls in the county form very close sisterhood with other in the same village. They do not want to marry, and if forced to marry, they stay in their own families, where they enjoy few restrictions. They do not want to return to the husband’s family, and some, if forced to return, commit suicide by drowning or hanging.

This “delayed transfer marriage” was unique to the Pearl River Delta… maybe because this was the center of the silk industry in China—one of the very few industries which employed women. And economic independence, as we all know, is the key to the survival of women-loving women under patriarchy. In China, this was doubly true, because of the heritage of footbinding and infanticide in the regions where marriage was a girl’s only prospect for financial security and her family’s only hope for getting her off their hands.

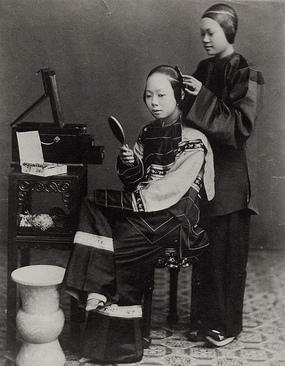

1868 photo of woman with bound feet

1868 photo of woman with bound feet And so the girls of Canton were allowed to survive and to develop their bodies. They were also educated.

But there was one more factor in their favor: lack of men. In the nineteenth century large numbers of Chinese men were emigrating to America. Now, some might insist that the “marriage resisters” were not so much militant lesbians, as frustrated spinsters turning to each other, because there weren’t enough good men to go around. But the case can be made that the removal of the men allowed women freer range in expressing their affection for each other.

In addition, there were religious ideologies that supported these women of the Golden Orchid. Many of them worshiped Guan Yin, a goddess of women who herself had rejected heterosexual marriage. One anthropologist recorded this creative explanation for same-sex bonding: If a woman believed she was predestined to marry a certain man, and he happened to reincarnate as a woman, she would still be attracted to him as her predestined mate!

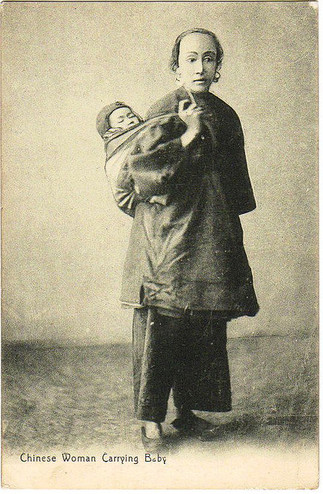

19th century working-class woman with unbound feet

19th century working-class woman with unbound feet Although the two women living together cannot be said to have the form/equipment of a man and a woman, they nonetheless enjoy the pleasure of male-female [intercourse.] Some say that they use friction or rubbing force, others say they use “mechanical devices.” … They adopt a daughter to inherit their property. When the adopted daughter also forms Golden Orchid sworn sisterhood with another woman, the woman is treated like a daughter-in-law.

Apparently, the women of the Golden Orchid understood the need to incentivize same-sex unions along the same lines at patriarchal marriage!

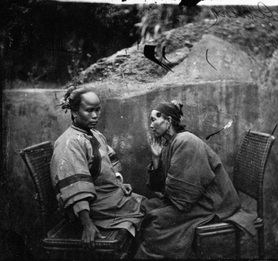

Rare 19th century photo of two women talking

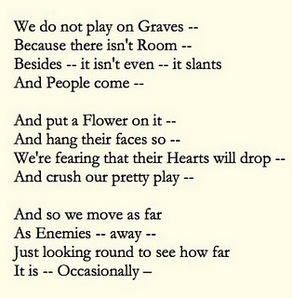

Rare 19th century photo of two women talking There were various ways in which sworn sisters were pledged to each other.... a pair of girls or women would take mutual vows never to marry and never to part company. The Chinese term for sworn sisters was “shuang chieh-pai, “ “mutually tied by oath.” Very often, these girls or women had spent a large part of their childhood together... Sworn sisterhood, however was not limited to twosomes. It often comprised a larger association of many women who were committed to each other in friendship and who formed an organized antimarriage grouping.

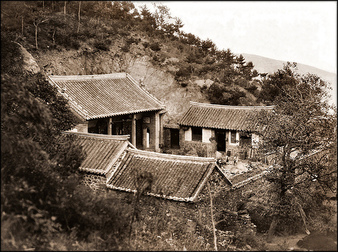

The sworn sisters lived in “vegetarian halls “ or “spinsters’ houses.” The former were residential halls for a somewhat subversive Buddhist sect which had been outlawed for political militancy. Girls living in these halls were expected to practice “self-cultivation “ by eating vegetarian diets and abstaining from sex with men. The “spinsters’ houses” were more secular, and vegetarianism was not required. Both institutions provided for women in their old age. There were retirement and death benefits, and there were also funds for celebrations and for emergencies.

Some of the vegetarian halls had libraries, and in these were found “good books,” treatises written by Buddhist nuns, urging girls to resist marriage and representing such resistance as an act of moral courage. These teachings even went so far as to depict suicide as an honorable alternative to arranged marriages. Sworn sisters, sometimes as many as six, had been known to drown themselves together rather than see one of their number married against her will.

Guan Yin, Female Bodhisattva

Guan Yin, Female Bodhisattva Marjorie Topley, the anthropologist who did the original work on marriage resisters in the 1950’s, claims that lesbianism was common among the tzu-shu nu. She notes that lesbian practices were called “grinding the bean curd “—a reference to a dildo made from silk and packed with bean curd.

The collapse of the silk industry and the threat of Japanese invasion in the 1930’s, forced “sworn sisters” to retire early to their spinsters’ houses, or to migrate to Hong Kong or Singapore as domestic workers, where they lived in “kongsi,” dwellings of women from the same region in China. The women of the kongsi would not take jobs in establishments which had fired another member of the kongsi. Many of these houses carried on the tradition of marriage resistance, and some even established banks for the purpose of making loans to the members. Single women would sometimes adopt daughters, but it was more common for sworn sisters to adopt jointly.

Although the Communists, who considered the resisters “counter-revolutionary,” wiped out the movement in China, some of the tzu-shu nu were still surviving in the 1990’s survive in Singapore and Hong Kong, keeping alive the tradition of their vows: “that there might be nothing but truth us.”

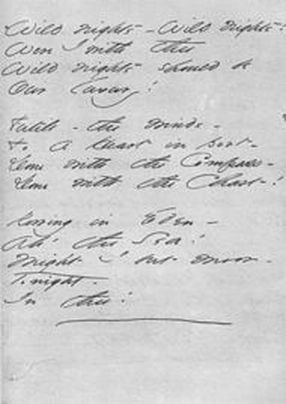

Qiu Jin in men's clothing

Qiu Jin in men's clothing ------

\

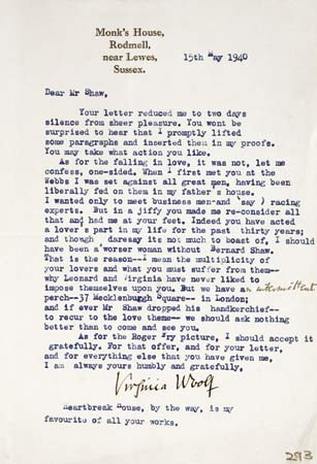

And I appreciate the reminder from an anonymous reader to footnote my sources... I did read the entry in Lesbian Herstories and Cultures... and the other two sources were internally referenced in their article:

Sankar, Andrea. "Sisters and Brothers, Lovers and Enemies:

Marriage Resistance in Southern Kwangtung." Journal of Homosexuality 11:3-4 (1986): 62-82.

Zimmerman, Bonnie. Lesbian Histories and Cultures: An Encyclopedia. New York: Garland Publishing, 2000.

Wolf, Margery, Roxane Witke, Emily Martin, ed. Women in Chinese Society. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1975.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed