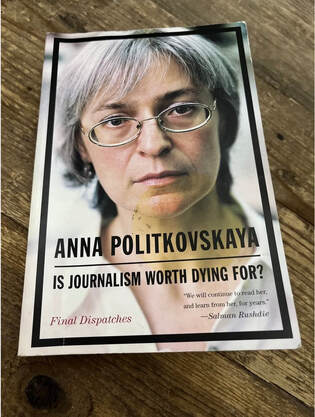

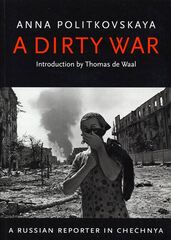

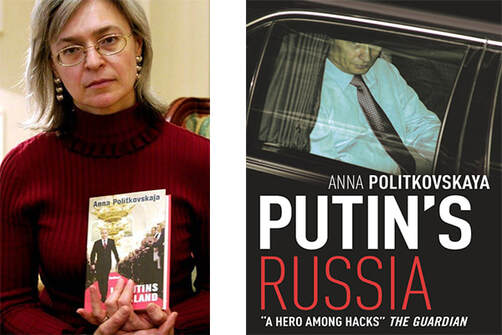

Politkovskaya was a Russian journalist whose fearless, behind-the-scenes coverage of the Chechen war had exposed human-rights abuses in Russia’s southern province of Chechnya, where tens of thousands have been killed during two Kremlin campaigns. She documented not only the brutality of the conflict, but also the massive corruption and moral corrosion that was occurring at all levels and on both sides. She was not afraid to name names, and, on at least one occasion, to print the official’s phone number, inviting her readers to register their disgust personally.

"Right now I have two photographs on my desk. I am conducting an investigation about torture today in Kadyrov’s prisons, today and yesterday. These are people who were abducted by the Kadyrovtsi [members of Kadyrov’s personal militia] for completely inexplicable reasons and who died… " (Politkovskaya/ RFE)

At this point, the interviewer suggested that perhaps these were individual cases, representing only a small percentage of abuses. Politkovskaya responded in no uncertain terms:

Politkovskaya was as unequivocal regarding the Chechen prime minister:

"Kadyrov is the Stalin of our times. This is true for the Chechen people. He’s a coward armed to the teeth and surrounded by security guards… Personally I have only one dream for Kadyrov’s birthday: I dream of him someday sitting in the dock, in a trial that meets the strictest legal standards, with all of his crimes listed and investigated."(Politkovskaya/ RFE)

Was Politkovskaya’s assassination a response to this broadcast? Certainly she had been aware of the danger. Kadyrov had publicly vowed to murder her. According to her, “He actually said during a meeting of his government that Politkovskaya was a condemned woman.” (Hearst) But journalism is a dangerous profession in Russia. Twenty-three journalists had been killed there between 1996 and 2005, many in Chechnya, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists. At least twelve have been murdered in contract-style killings since Putin came to power. (AP)

The mystery is not so much that Politkovskaya was killed, but where she found the courage to continue working in the face of so much danger. After all, she had been receiving death threats since 1999, when she first began documenting human rights abuses in Chechnya. (WiPC) Members of her family had been threatened. A few months before her murder, unknown assailants tried unsuccessfully to break into a car her daughter, Vera, was driving. As the obituary in the Guardian comments,

Who was this woman Anna Politkovskaya? Where did she find her courage? Was she super-human, immune to threats of torture and death?

Certainly, she could have chosen a different life. Born in 1958 in New York, the daughter of United Nations diplomats from the Ukraine, she had a privileged background and dual citizenry. After graduating from Moscow University in 1980, she wrote for the national daily Izvestia before switching to the smaller, independent presses. She had a husband and two children. Never envisioning herself as a war correspondent, Politkovskaya stated, “I was interested in reviving Russia’s pre-revolutionary tradition of writing about our social problems. That led me to writing about the seven million refugees in our country. When the war started, it was that that led me down to Chechnya.” (Hearst)

But professional drive cannot explain the courage of Politkovskaya. There must have been something more, something deeper.

There are some clues in her account of the Moscow theatre hostage crisis in 2003, when renegade, Chechen hostage-takers, requested her as a negotiator. They had seized a theatre and were holding 850 people hostage. Unlike the sparse and impersonal accounts of her torture in 2000, this report is surprisingly subjective:

'So, doctor, you are trying to make a name for yourself?' the masked man keeps mumbling. But the doctor is seventy years old. He has already achieved so much in his life that he does not have to think of making a name for himself. His career is quite accomplished.

That is what I try to point out, and a heated exchange of words follows. I understand that I need to cool it off or else. I have an idea of what 'or else' means.

The masked man steps aside and keeps mumbling, 'Why did you have to point out that you treated Chechen children, doctor? You, doctor, single out Chechen children. Do you mean to say that we are a species apart, that we are not human?'

This is a familiar tune. I have to interfere because I cannot stand this any longer. 'All people are the same. They have the same skin, bones and blood,' I say.

Suddenly this simple thought has a peace-making effect. My legs turn to water and I ask for permission to sit down on the only chair in the middle of the lobby… I stop shaking for a while." (Politkovskaya)

But what her account demonstrates is that, shaking and barely able to stand, she was human and terrified. At the same time, she could not ignore the verbal harassment of her companion on this dangerous and humanitarian mission. In what might seem to others a minor point under the circumstances, she is scrupulous about setting the record straight, and in doing so, recovers her spiritual poise. Her focus is on the suffering of those caught in the middle of the conflict, the hostages—and especially the children. But her sympathy for the hostages does not keep her from quoting with empathy her captors’ words, “You never give our children any food during mopping operations, so let yours suffer, too.” (Politkovskaya)

That was the power and the genius of Potlitkovskaya—her ability to hold onto the larger context of governments, political parties, military campaigns, while at the same time focusing on the often-contradictory details of individual experience and accountability. It was this focus on the immediate suffering, the outrage of the moment, that was the hallmark of her journalism—and possibly the secret behind her tremendous courage.

Associated Press. “Russian Reporter Killed in Moscow.” 7 October 2006

http://www.theglobeandmail.com/servlet/story/RTGAM.20061007.wrussian- journo1007/BNStory/International/home

Hearst, David. “Anna Politkovskaya: Crusading Russian Journalist Famed for her Exposés of Corruption and the Chechen War.” The Guardian 9 October 2006 http://www.guardian.co.uk/russia/article/0,,1890838,00.html

Maineville, Michael. “The Silencing of Anna Politkovskaya.” Spiegel Online 13 October 2006 http://www.spiegel.de/international/0,1518,442392,00.html

Politkovskaya, Anna. “Inside a Moscow Theater with the Chechen Rebels.” International Women’s Media Foundation, http://www.iwmf.org/features/anna

Politkovakay, Anna, interviewed by RFE/RL. “Russia: Anna Politkovskaya’s Last Interview.” Radio Free Europe/ Radio Liberty 9 October 2006 http://www.rferl.org/featuresarticle/2006/10/fc088b08-0cbd-4800-b2ff-f00f5494fa5e.html

Smith, Becky. “Independent Journalism Has Been Killed in Russia.” The Guardian 11 October 2006

http://www.guardian.co.uk/russia/article/0,,1896806,00.html

Writers in Prison Committee, International PEN. “International PEN Statement on the Murder of Russian Writer and Journalist, Anna Politkovskaya.” International Freedom of Expression Exchange 7 October 2006 http://www.ifex.org/en/content/view/full/78140

RSS Feed

RSS Feed