“Born and raised in Brooklyn, Allegra studied theater at Bennington College and Hunter College, graduating from New York University in 1977 with a Bachelor's degree in dramatic literature, theater history and cinema. She worked as a construction electrician to support her writing and dancing, reviewed dance, theatre and film productions as a freelance cultural journalist, and produced lesbian and feminist-oriented radio programming for WBAI from 1975-1981.

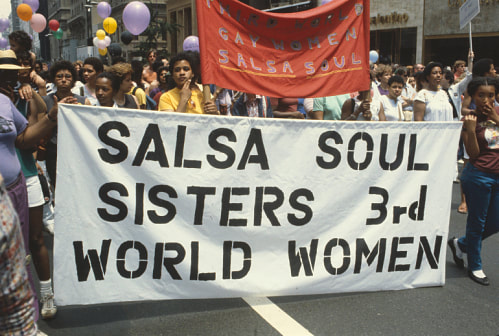

Allegra was an early member of the Jemima Writers Collective, the first black lesbian writing group in New York City. The collective grew out of the Salsa Soul Sisters, the oldest black lesbian organization in the United States, and was founded to encourage black women writers to share their creative work with each other in a supportive environment. Fellow members of Jemima included Candace Boyce, Georgia Brooks, Linda Brown, Robin Christian, Yvonne Flowers (Maua), Chirlane McCray, Irare Sabasu, and Sapphire. Allegra later joined the Gap-Toothed Girlfriends Writers Workshop.

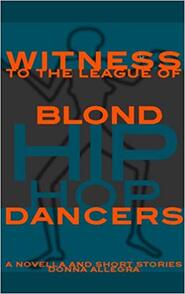

In this blog, I wanted to share excerpts from her short story “Dance of the Cranes.” This was originally published in the anthology Black Like Us: A Century of Lesbian, Gay and Bisexual African American Fiction. It’s also included in Witness to the League of Blonde Hip Hop Dancers. “Dance of the Cranes” is about a fourteen-year-old, black, lesbian butch who is struggling with issues of sexuality and gender, and also wrestling with the homophobia she is encountering in her community of dancers. In the story, this girl, Lenjen, finally sees someone who looks like her in her African dance class—an older butch dancer named Lamban, and the two are paired together by the instructor to perform the Dance of the Crane. As the pair demonstrate their dancing, the rest of the class bears witness and celebrates the tribal/familial bond of these two outsiders, and in doing that, Lenjen’s trauma and Lamban’s estrangement are healed.

This intersecting pain of butch-phobia and homophobia, coupled with racism, misogyny, and classism were familiar themes in Allegra’s life.

Writing in the late 1990’s when the Internet was still in its infancy, Allegra was ahead of her time in naming the specific intersecting oppressions that she faced as an emergent lesbian writer of color. Her exposés are exceptional in their candor about how these oppressions shaped her experience. In 1997, her essay, “Inconspicuous Assumptions,” was published in Queerly Classed: Gay Men and Lesbians Write About Class. In it, she ticks off these assumptions:

- One particular cultural base should define universal standards in literature.

- The white male experience is central.

- All lesbians are white and upper-class.

- Writers have money, hence plentiful free time.

- The playing field for publishing is level for LGBT writers.

- Only white males take their craft seriously.

Fast-forwarding twenty-five years, it’s interesting to look at her list of “inconspicuous assumptions” and note how much more conspicuous they are today—thanks to the arduous efforts of writers like Allegra. It’s also interesting to note how many of the changes in the field of publishing have been superficial, especially with regards to working-class writing and lesbian-of-color representation. The lesbian butch voice remains underrepresented in all genres.

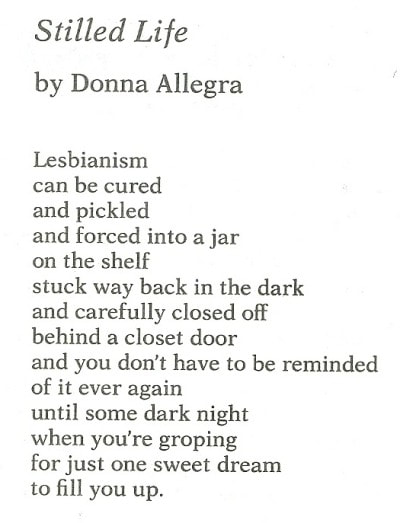

Here is Allegra, heartbreakingly candid about how the absence of kindred literary role models impacted her self-image:

"A telling marker of ruling-class viewpoint has to do with whose lives make it to the page and just whose story is told. The upper classes had their dramas enacted as the experience we were supposed to take as “universal.” Shakespeare’s leading characters were court royalty. Well, I’m not exactly the queen of England, but I first recognized myself as a lesbian by name in the story of a British noblewoman. Before I finished Radclyffe Hall’s The Well of Loneliness, I knew my common bond with Stephen Gordon made us sisters. I had all the symptoms of her situation. As a tomboy long past the age when I should have outgrown the “phase,” I waxed romantic over pretty girls; boys were fit companions, but of no interest beyond that. Clearly, I was destined to ride horses across the British countryside and become a champion fencer!

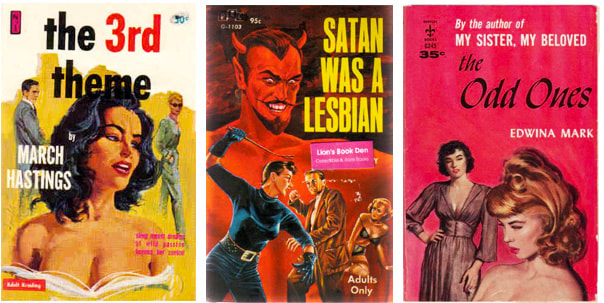

Lesbian pulp fiction of the late 1950's and early 1960's

Lesbian pulp fiction of the late 1950's and early 1960's … Natalie Barney, Sappho, Gertrude Stein, and Djuna Barnes… wrote about the concerns of upper-class women. They who lived on unearned income would likely take one look at me and imagine a cleaning woman, or, at best, a housekeeper. Not much probability that they would recognize a sister spirit, because class identification is so much more rigid in the upper registers of the social scale.

The literature that spoke clearly of my possibilities was the soft-core lesbian porn of the 1960’s—writes like Ann Bannon, March Hastings, Joan Ellis, Dallas Mayo, and Sloan Brittain, whom I happened upon in the adult book sections of drugstores."

“Lenjen wanted her mother to understand how she drank from the current of energy that flowed from the dancing women, that they were the ones who enriched her blood. She wasn’t putting her passion on the floor for some mating game. But [her mother’s] mind was set, and Lenjen didn’t want to whine after her to explain.”

The girl has noticed an older woman at the dance classes, who has been away for a while but is just returning. She finds herself pulled toward this woman who “wore African pants and didn’t hold back from trying the men’s steps."

The older woman, Lamban, is an older version of Lenjen. I suspect that she represents the missing role model in Allegra’s own youth. In Lamban, we see the development of themes just emerging in the teenager and discover the secret behind her long absence from dance classes:

Lamban still grieved that being a lesbian could make her an outlaw to a group of people who did the most spiritually sustaining thing she knew in life. She’d needed all those months away to love herself again. The time in seclusion let her grow perspective, like new skin. That’s how lobsters did it—when the old shell became too small for the mature body, they’d go to a protected place where they could shed the old covering safely. In that haven, they could curl naked and vulnerable until a new covering grew in.”

The final dance of the evening is the lenjen, the dance after which the teenager had been named—the Dance of the Cranes. The teacher pairs Lamban and Lenjen. In the description of the solos, Allegra describes a deeply healing ritual between two members of a people who have survived a diaspora, but who are also survivors of a different kind of dispersement—lesbian butches unable to find their people and despairing of a home they have never known:

At the end of class faces glistened with the sweaty joy fashioned from something cleansed and set free. Lenjen and Lamban smiled at, looked away from and back to one another. Lamban pulled the girl to her and held her in a long, strong hug. She felt people smiling their way. And why not smile upon them? The community had just witnessed a mighty rite of passage. Two queer birds had stretched their wings, each finding a new level of flight in the dance of the cranes.”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed