"What have been described as “seductive behaviors,” were, in fact, an aggregate of cues developed in a perpetrator-victim scenario, and it is instructive for women to note the universality of this code among males who choose to read them at face value. Ask these same men to imitate Marilyn Monroe ‘s facial expressions, postures, or speech patterns, and they will be quick to tell you how ridiculous, how childish, how undignified they feel. Apparently behaviors that are seen as natural and even desirable for women, are read as degrading and absurd for men. The mystique of femininity or the bald facts of dominance? The sexual behavior for women that patriarchy wants to idealize is identical to that of an enslaved child."

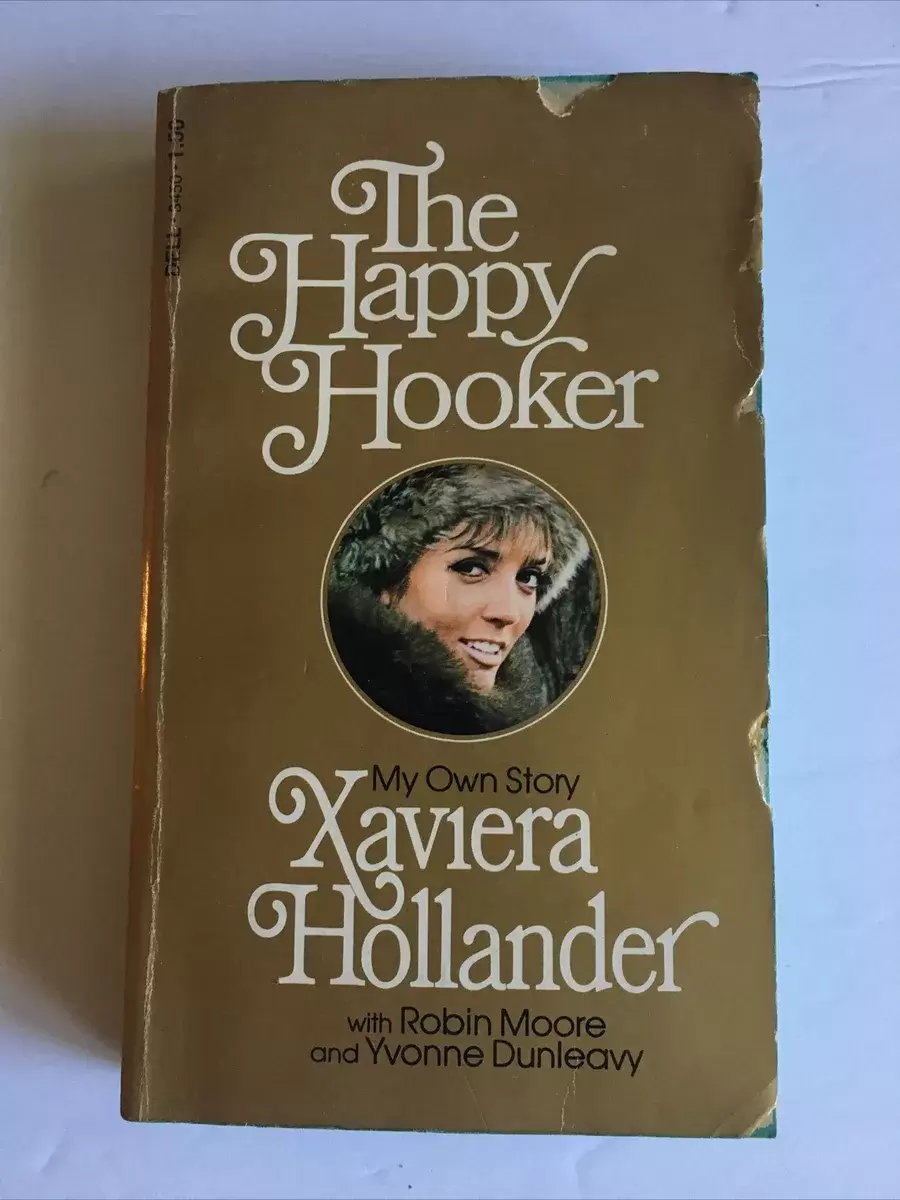

In 1972, The Happy Hooker by Xaviera Hollander burst onto the scene, becoming an international bestseller and launching its author into instant celebrity. The book seemed to offer proof positive that the so-called “Sexual Revolution” of the 1960’s had indeed succeeded. The publisher crowed, “Far from the conventional image of the prostitute, Xaviera is well-read, articulate, fluent in half-a-dozen languages, and bursting with charm and joie de vivre.”

In the book, Hollander recounted in titillating prose her experiences as a prostitute and then as a madam in New York City. It didn’t hurt sales that her appearance corresponded with the stereotype of the “blonde bombshell,” and the fact that she was from the Netherlands lent her an air of European sophistication. Hollander was lauded as a completely liberated woman whose apparently insatiable sexual appetite was nothing more than the natural expression of a healthy libido. The one episode in the book where she was beat up and very nearly murdered by a john is treated as an unfortunate and fluke event, in what was otherwise consistently characterized as an empowering and fulfilling profession.

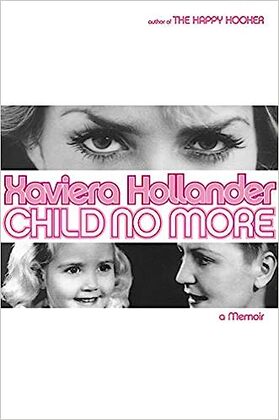

The Happy Hooker sold fifteen million copies, and was made into a movie starring Lynn Redgrave. Hollander went on to write a sex advice column for Playboy, and several more books about her sexy escapades. Then, in 2002, she published a memoir that was very different from her other books. Titled Child No More, this book did not make any best-seller lists or attract any movie deals. It was, in fact, a Holocaust memoir.

Hollander’s mother, an Aryan, was living in Germany with her family in the 1930’s, when Hitler came to power. She became engaged to a Jewish friend of the family, but, panicking at the wedding, she ran away. A gang of Nazi teenagers cornered her on the street, beat her and stoned her, shaved her head and forced her to wear a sign with the words “Jew whore.” Her family, shocked and terrified, smuggled her into the Netherlands. Here she met and married a Jewish doctor, who was the head of a hospital in Indonesia. Their courtship had been brief, and even before they left for Surabaya, Hollander’s mother discovered that her new husband was a notorious womanizer.

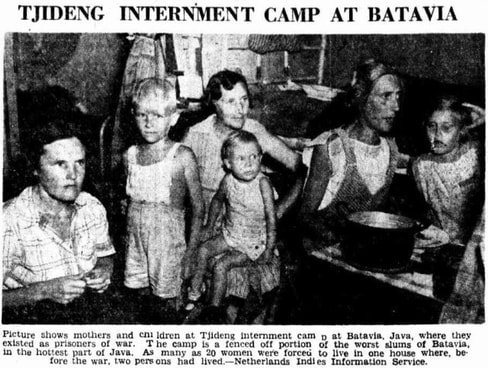

In June 1943, Hollander was born, and two months later, she and her mother were taken to a Japanese concentration camp. Her father had already been taken prisoner. Hollander’s mother had the option of going to a camp for Aryan women, where conditions were not so brutal, but she refused to be separated from her daughter, and chose to join the Jewish women with their children.

Hollander recounts how she saw soldiers repeatedly caressing and fondling her six-year-old companion, who was being prostituted by her mother for food. She remembers how all the women had to crouch down “like frogs” in front of the soldiers:

"The women were obliged to accept all kinds of humiliation; the slightest sign of disobedience was punished with mindless severity. A favorite practice was for the man to thrust his fingers into the sides of a woman’s mouth and then tear it open from cheek to cheek, leaving a bleeding gash where there had been a mouth. As more and more savage soldiers took over guard duties, there were many who took delight in inflicting torture for its own sake. They would rip open mouths without even the justification of an act of disobedience or a glance of defiance, just as they would inflict beatings as the whim took them." (Hollander, p. 54)

Hollander describes what may be her most intact memory:

"One image survives of me, a lonely, frightened child sitting on a tiny suitcase containing everything I owned, sobbing in terror as a squad of soldiers marched past, each sporting three or four watches stolen from the women, shouting strange words at the top of their voices. Kirei, kirei: bow down, bow down! There was the uncanny sight of a group of women, bowing and frog-squatting, while on the other side of a barbed wire fence, rifles at the ready, these frightening men strode by. I burst into an uncontrollable torrent of tears. Where was my mother? No one came to dry my tears. An orphan has to look after herself. "(Hollander, p. 59)

As a teen

As a teen The war ended and the camps were liberated, but before Hollander and her mother were reunited with her father, she suffered another traumatic experience. Climbing a dead tree, she took a fall that resulted in her groin being impaled with a dead tree branch. Taken to the hospital, she remembers there were two doctors, who playfully told her to choose which one would treat her. Unknowingly, she chose her own father. He also failed to recognize her.

He apparently performed surgery on her torn vulva, and Hollander’s memories of this episode are bizarre. She remembers his “hypnotic power,” as “magic seemed to flow from his hands as they brushed my most private region.” Whether he was sexually inappropriate or she was overlaying previous trauma memories, she would write, “… there was that peculiar attraction at first sight. And in the years that followed, the precocious eroticism his loving, skillful hands had aroused in me would develop into a powerful emotion, little short of obsession.” (Hollander, p. 71)

After the war, Xaviera with her mother.

After the war, Xaviera with her mother. How much of her eagerness to please men sexually could be attributed to a post-traumatic, generalized Stockholm Syndrome? Was the peculiar form of mouth torture that she noted a result of women not smiling enough at their degradation, of not appearing “happy” enough at their sexual violation? Hollander noted that, in the camps, it was clear that some women were not starving and were visibly better off than others. Later, she would understand that these were the women who were prostituting themselves. How deep an impression did that information make? Could her celebrated hypersexuality have been a response to inappropriate sexualization as a toddler—either in the camp or at the hands of a father whose lack of sexual boundaries was a constant source of conflict in his marriage?

In Hollander’s own words, “A child’s character is like clay, and my confinement in that hell behind the bamboo wall certainly molded my character.”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed