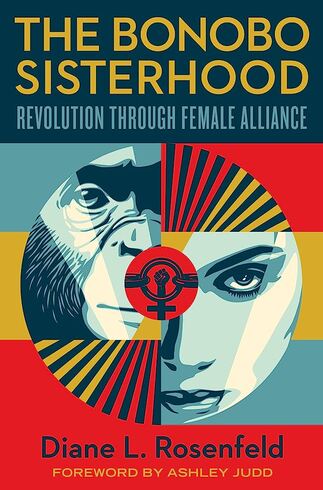

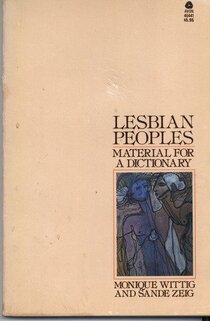

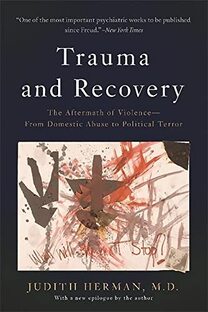

What am I talking about? I’m talking about The Bonobo Sisterhood: Revolution Through Female Alliance, a new book by Diane L. Rosenfeld.

I'm not happy with it. Read on...

The book is a passionate plea for women to model ourselves after the bonobos, a species of great apes. They are the last of the great apes to be scientifically described, because they weren’t recognized as a separate species until 1929. The bonobos began to get a lot of press during the Second Wave, because, unlike females from other species of great apes-- including humans, the bonobo females are empowered. They are not stalked, threatened, battered, raped, or murdered by the males. Their culture and their species are peaceful.

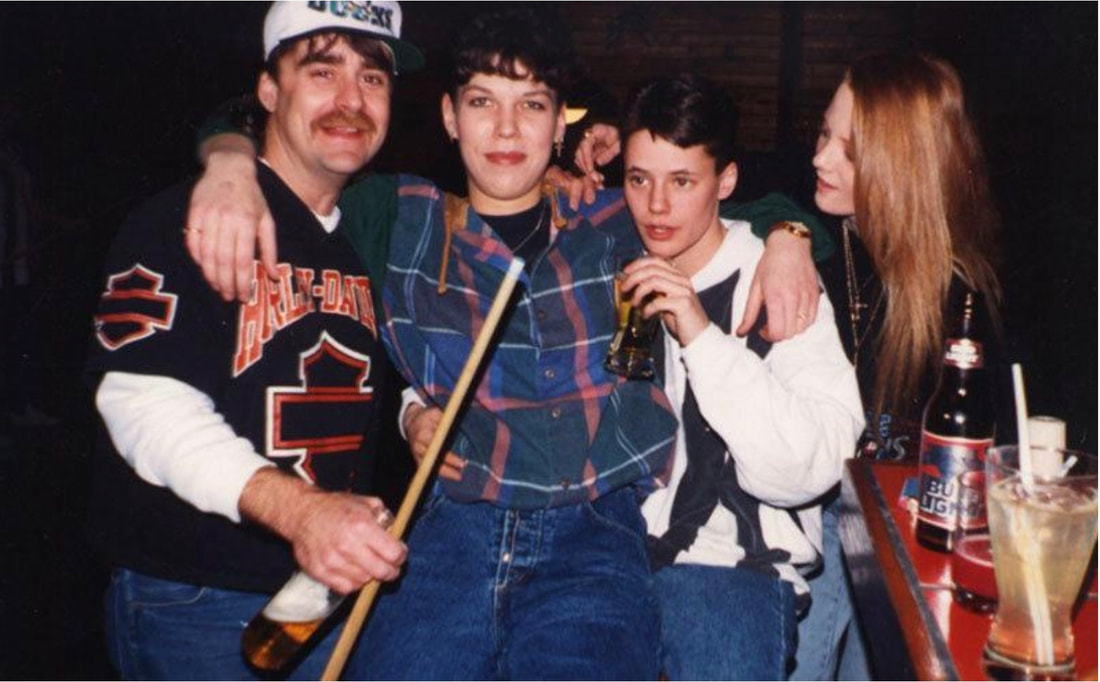

Dr. Diane Rosenfeld

Dr. Diane Rosenfeld Rosenfeld’s credentials on the subject of violence against women are impressive: She was the first Senior Counsel in the Office on Violence Against Women at the United States Department of Justice, and before that she was an Executive Assistant Attorney General at the Illinois Attorney General’s Office. She’s got a law degree the university of Wisconsin and a secondary law degree from Harvard. Her research areas include “Title IX and campus sexual assault prevention and response; prevention of intimate partner homicide; and addressing commercial sexual exploitation of women and girls.”[from the Harvard Law website]

Female bonobos

Female bonobos What I am not in awe of is her appropriation of the bonobo. Her book is, frankly, homophobic. What sets these female apes apart from all the other great apes is their sexuality. Take a look:

“More often than the males, female bonobos engage in mutual [that is "same-sex"] genital-rubbing behavior, possibly to bond socially with each other, thus forming a female nucleus of bonobo society. The bonding among females enables them to dominate most of the males. Adolescent females often leave their native community to join another community. This migration mixes the bonobo gene pools, providing genetic diversity. Sexual bonding with other females establishes these new females as members of the group.” [Wikipedia]

And how did this amazing adaptation arise, you ask? Well...

“Bonobo clitorises are larger and more externalized than in most mammals; while the weight of a young adolescent female bonobo 'is maybe half' that of a human teenager, she has a clitoris that is 'three times bigger than the human equivalent, and visible enough to waggle unmistakably as she walks.' In scientific literature, the female–female behavior of bonobos pressing genitals together is often referred to as genito-genital (GG) rubbing. This sexual activity happens within the immediate female bonobo community and sometimes outside of it. Ethologist Jonathan Balcombe stated that female bonobos rub their clitorises together rapidly for ten to twenty seconds, and this behavior, ‘which may be repeated in rapid succession, is usually accompanied by grinding, shrieking, and clitoral engorgement;’ he added that it is estimated that they engage in this practice ‘about once every two hours’ on average." [Wikipedia]

Dr. Rosenfeld makes absolutely ZERO mention of bonobo sexuality, except to note that the females, as a result of their remarkable sisterhood, have empowered themselves to have sexual autonomy. In other words, she puts the cart before the horse and then eliminates the horse altogether.

Understandably, that cart is not going anywhere.

Without female-to-female sexual bonding there is no bonobo sisterhood, no powerful alliance to counter male aggression, no acceptance of females into new tribes, no intergenerational female bonds.

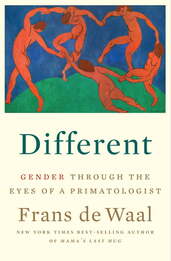

Her omission is no oversight. It flies in the face of primatology and common sense. This evolved, large, frontally-located clitoris is the engine that drives the female bonding. In fact, primatologist Franz de Waal notes in his book Different: Gender Through the Eyes of a Primatologist that the levels of oxytocin, the “love drug,” are higher in the urine of female bonobos after sex with another female... higher than after sex with males. Enhanced oxytocin production has been seen as a hormone to facilitate childbirth, but it is probable that it significantly enhances bonding.

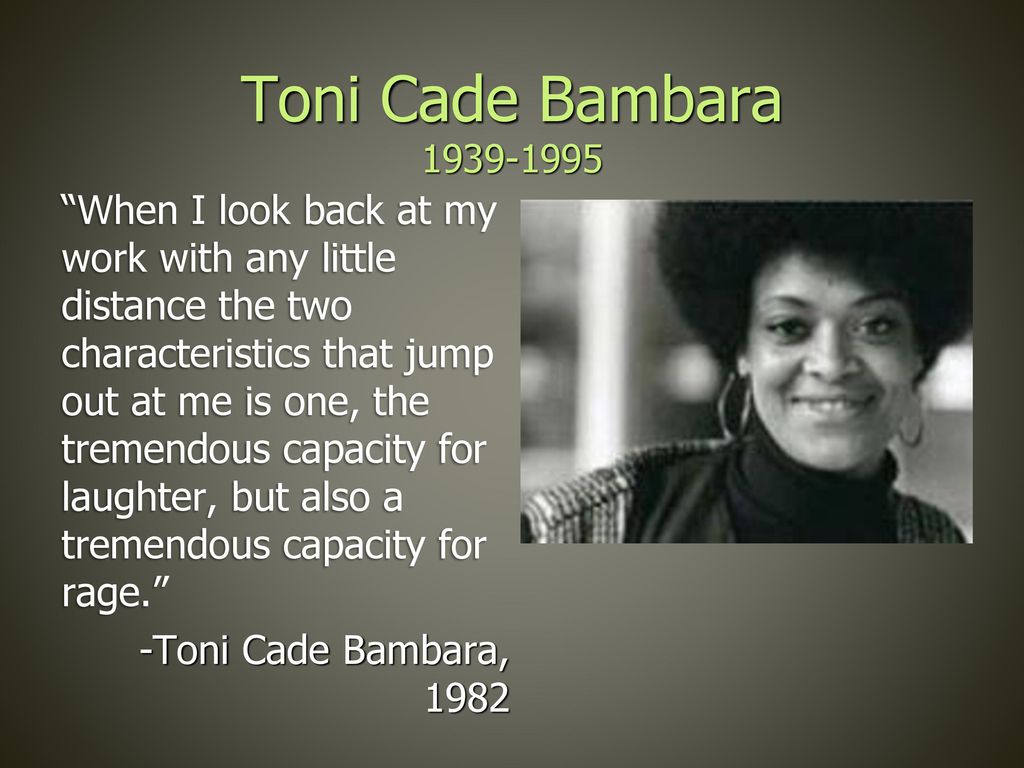

Because if she did, she might have to acknowledge that this same-sex activity among females, most notably among lesbians, does indeed lend itself to unique female bonding. Lesbian history shows us over and over how lesbian women have confronted males, established alternative all-female institutions, led the fight for feminist social reforms, and developed counter-cultural narratives to challenge the patriarchy.

Female chimpanzees

Female chimpanzees This attitude is hugely disrespectful to the millions of women across the millennia who have not wanted to be terrorized and abused. Every woman knows that it is males who perpetrate and aggress against us and against our children, especially our daughters. If the solution was as simple as reading a book about the power of female alliances, I’m sure that book would have been written in hieroglyphs and those alliances would have been made centuries ago.

There is another omission in Rosenfeld’s book. She fails to note that even though chimp culture is patriarchal and the male chimpanzees will attack and batter female chimpanzees, there are no records of the males murdering the females. In fact, humans are the only great ape species that murders its females. After all, how anti-evolutionary can you get... murdering the mothers of the tribe? So, how is it that the chimps don’t murder the females?

Well... Chimpanzees are sexually segregated. The males prefer the company of males, and the females prefer the company of females. Females do not go off with male partners and live in isolation with them. The females stay together, raise their offspring together, and sleep together within earshot of each other. When they do mate, it is in the open and in daylight, where other chimps can witness and intervene.

Overlooking the obvious

Overlooking the obvious The solution to male violence against women is not cherry-picking primate outcomes and mistaking them as starting points. The solution is not as simple as “sisterhood.” If she had consulted with lesbians, studied our sexual bonding and alliances, she would have understood that our culture constitutes a resistance movement. It comes at a price.That price is precisely the stigma that Rosenfeld hopes to avoid with the unscientific omissions in her thesis.

I am reminded of the fable of the drunk person who is looking for their lost keys under the lamppost, when they dropped them somewhere in the dark. Rosenfeld’s search is a cheerful one, and positivity abounds. Lots of light. This won’t be hard at all. We just need to wake up to this new idea. But the key to solving male violence lies outside the glow of the heteronormative, patriarchal lamppost. I would submit, considering the bonobo example, that heteronormativity is itself a patriarchal concept. Historically, it has never worked in our favor. The key to female autonomy lies in the culture and history of lesbians. The bonding is in the body, and it always will be.

And yet she gaslights her readers, throwing lesbians under the bus, and arguing for the "logic of the bonobo sisterhood," when that very logic rests on a foundation of immediate gratification: seeking maximum sexual pleasure and finding it with other females. The bonobo alliances are effect, not cause.

Rosenfeld has an whole section on the subject of compliance sex, excoriating it and expressing a longing for a social system that precludes unwanted sex. The sad truth is that her book is itself an artifact of compliance sex culture.

Self-defense? Check out the history of lesbians. Alliances to protect women and children? Collective self-defense? Check out the history of lesbians in any reform movement for women. Check out our history with female-only educational institutions, with the WAVES and the WAACs (female-only military branches), with the battered women's shelters, the rape crisis lines, the suffrage movement on two continents. Refusal of compliance sex? We are the champions. In fact, our resistance to unwanted sex is the source of our stigma. The very stigma that this book so rigidly and so glaringly enforces.

The Bonobo Sisterhood is a Trojan horse of a book, and I am calling the author to account for her damaging, disingenuous, homophobic, science-denial omissions and her appropriations.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed