Now you can bring forth that “thing that is in you” in poetry, or painting, or dance, or theatre, or music, or story. And if you bring it forth as story, it may be a story that only you can interpret, and that’s okay.

But stories can also be propaganda. That’s why we’re going to synapse around the whole thing of “story” today. Because the propaganda stories can get us thinking along lines that will cause us to betray our own best interests… and often, in scrubbing off the layers of falsehood in popular myths, like fairy tales or folklore or patriotic myths, we can recognize some life-saving truths that underlie the distortion or the appropriation. Kinda like when you find a masterpiece underneath that painting of dogs playing cards.

So that’s what we’re doing today.

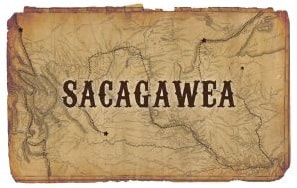

From Three Forks, Montana to Stanton, North Dakota... but this route is "as the crow flies." Sacagawea, child prisoner, probably walked twice this distance.

From Three Forks, Montana to Stanton, North Dakota... but this route is "as the crow flies." Sacagawea, child prisoner, probably walked twice this distance. Now, those aren’t bad reasons for telling stories… except that in the case of Sacagawea, they aren’t the whole truth. And the parts of the truth that they are hiding are really, really important parts of the story. And there is also a story underneath that is not being told.

So, let’s get out those tools for scraping off those layers of cultural whitewash and mansplainery, and see a little bit more of what’s really going on in this story.

Sacagawea was born into the Shoshone tribe in Idaho around 1788, and when she was eleven or twelve years old, she was in a Shoshone hunting camp near what today is Three Forks, Montana, that was attacked by the Hidatsa, a Siouan tribe of Native Americans. In this raid, four Shoshone men and four Shoshone women, and several boys were killed. Sacagawea was taken captive and enslaved. Remember, she’s eleven or twelve years old. And these Hidatsa force her to walk with them back to where they live in North Dakota, which is about five hundred miles away, as the crow flies. So here’s this eleven or twelve-year-old child who has survived a massacre of family and friends, and she’s now enslaved, and she’s having to march for hundreds of miles back into North Dakota from Montana, and when she gets there, she is—you know—she’s still an enslaved child.

Triveni Acharya with children in India she rescued from child trafficking. There were no rescuers for trafficked indigenous girls in the 19th century.

Triveni Acharya with children in India she rescued from child trafficking. There were no rescuers for trafficked indigenous girls in the 19th century. Sacagawea conceived around the age of fourteen, and the reason we know this is because she was pregnant in the winter of 1804-5, when Lewis and Clark showed up in the Hidatsa village and started negotiating with Sacagawea’s perpetrator for his services as a guide. Lewis and Clark were the two men leading this expedition commissioned by the US government. They were leading twenty-nine white men and one African American man, who was enslaved. Sacagawea’s perpetrator told Lewis and Clark that the pregnant child was his wife, and he negotiated a fee for her services as a Shoshone translator—a fee that would be paid to him, of course. As her captor’s so-called wife, Sacagawea never received a dime for her services—or any form of compensation—for the work that she did.

The Bozeman Pass auto/train route today.

The Bozeman Pass auto/train route today. Sacagawea trekked on this expedition for two years, four months, and ten days. Sisters, she walked eight thousand miles with these white men and the African American enslaved man… with a baby on her back. She forded rivers and climbed steep mountains and crossed deserts and swamps in snow and rain and sweltering sun. She translated for the men, she foraged for them, she cooked for them, and she did the sewing, mending, and cleaning of their clothes… you know, the “women’s work.”

There have been whitewashing and mansplaining efforts to downplay her work as a guide, but the truth is, she was responsible for pointing out the pass they should take through the Rockies and the pass they should take into the Yellowstone basin… the Bozeman Pass. Kind of a big deal, locating these passes.

Statue of Lewis and Clark reaching the Pacific.

Statue of Lewis and Clark reaching the Pacific. One of the greatest services that Sacagawea provided was protection. By this time, Native American tribes had come to assume, and assume rightly, that any group of white men traveling into their territory probably constituted some kind of war party. They had learned that it was better to attack first and then try to figure out who they were later. But the fact that this group included a Native American woman with a baby was taken as evidence that these men came in peace. In other words, Sacagawea saved all their lives and probably many times over.

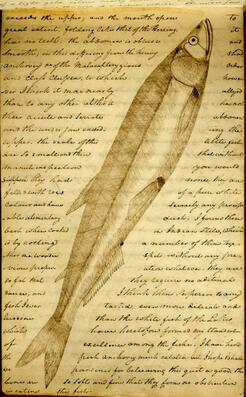

So, eventually, the expedition gets to the western part of Oregon, to the coast. And they set up a camp and start sending parties down to the beach to see the actual ocean. And these parties are reporting that some kind of “great fish” has washed up on the beach—possibly a whale. And, unbelievably, these men were not going to allow Sacagawea to leave the camp to go see it. Unbelievable. She had to beg and plead with them, and this was so unusual on her part, that Lewis wrote about it in his journal. And it really pisses me off that she did all this enormous work, as a child, with a newborn, involuntarily, and then when they finally reach their goal—the Pacific Ocean—where there’s this magical, giant fish, this eighth wonder of the world, they make Sacagawea beg and plead just to be able to see it. If there is ever any historical doubt about her degree of autonomy on this expedition, that should lay it to rest finally and forever. She had none.

I know. It’s a horrible story, isn’t it? Sacagawea was obviously heroically strong, but she was a victim throughout her short life. From age eleven, she was separated from her people and enslaved. She was a victim of ongoing rape from puberty and subjected to involuntary pregnancies.

It’s a story of endurance, but it’s not the story of multi-cultural diversity in the early years of the US. Sacagawea is not the poster woman for biracial marriage. She was obviously powerful, but she was not empowered. If there is any multi-cultural story to be told here, it is a shameful story of the collusion of powerful men—French, Hidatsa, and Anglo American—in the exploitation of an enslaved, female child. It’s a disgusting tale of adult males bonding through the bartering for forced labor and victimization of a Shoshone girl. However divergent their cultures, these men were all in agreement in their misogyny. They all colluded in characterizing the formalized child-rape arrangement as a legalized marriage.

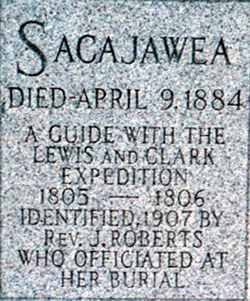

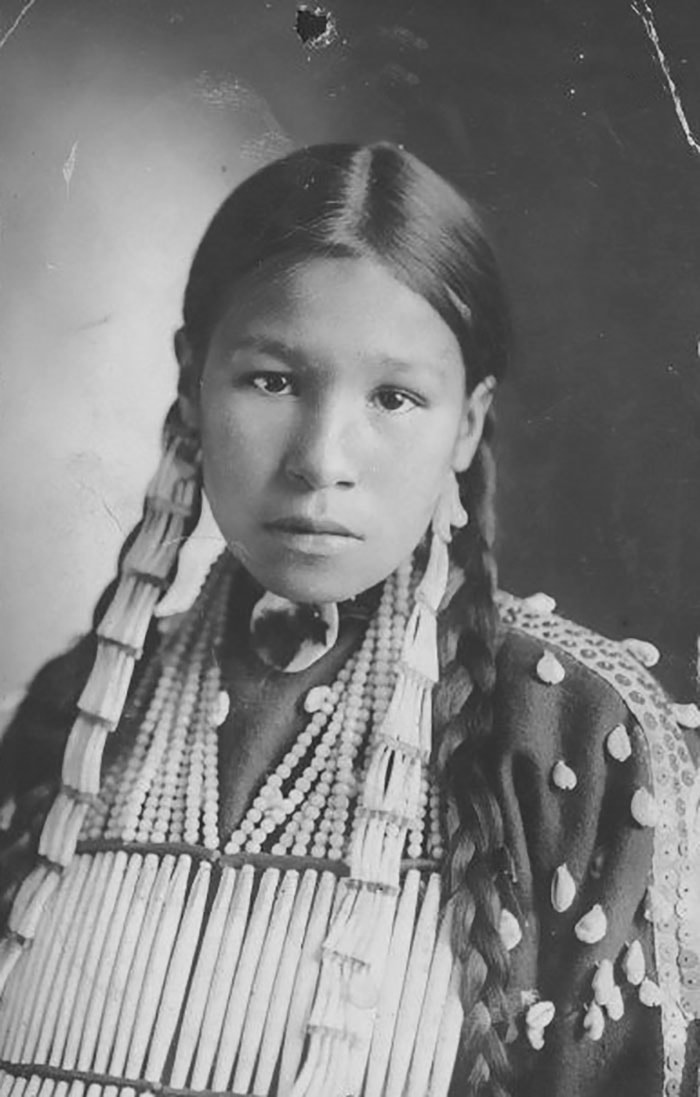

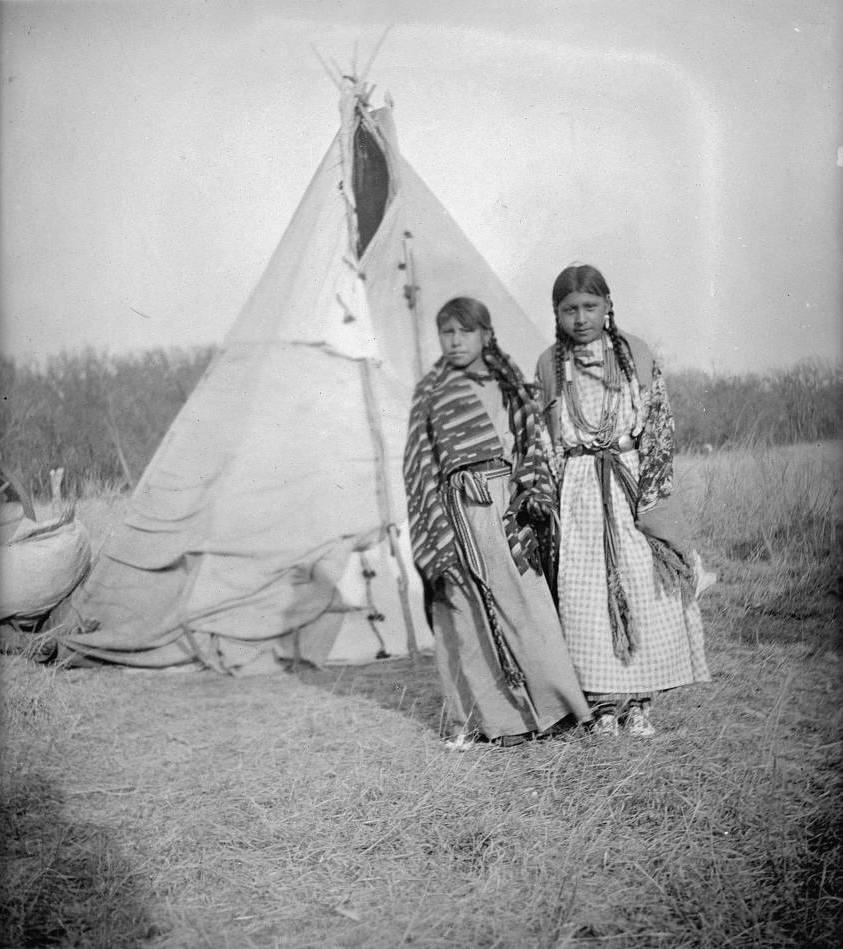

There are no photographs of Sacagawea. Here is a photo of an unidentified Native American teenaged girl from 1890.

There are no photographs of Sacagawea. Here is a photo of an unidentified Native American teenaged girl from 1890. So at one point in their travels, the expedition ended up camping at the very place where Sacagawea was captured and abducted by the Hidatsa as a little girl. This was the place where she lost her tribe, her family, her history, her culture, her freedom... and, sadly, her childhood. This was the place from which she was forced to undertake a journey of a thousand miles with her enemy.

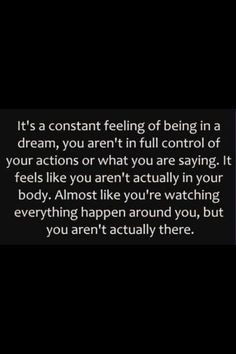

So, when the Lewis and Clark Expedition arrived at this former Shoshone hunting camp, Sacagawea told them the story of the massacre and here is what Lewis wrote in his journal: “I cannot discover that she shews any immotion of sorrow in recollecting this event, or of joy in being again restored to her native country; if she has enough to eat and a few trinkets to wear I believe she would be perfectly content anywhere.”

He seems to be describing her as someone who is kind of shallow or emotionally under-developed… “primitive” in the sense of being in some early stage of evolution or history. He appears to be comparing her affect to that which he believes he might experience, had he been in her shoes… which is as ridiculous as it is unfair. As a white, male colonizer, he has absolutely no context for understanding the trauma of her past, or the context of her ongoing rape and enslavement. He does not appear to understand that he is complicit in enabling her ongoing enslavement.

Depersonalization is a kind of complete loss of identity, which makes sense when you consider that her trauma was far from over. And when we consider that this is what Lewis wrote in his journal, it’s a description of Sacagawea that lets him off the hook. Since she doesn’t seem to register any kind of emotional response to this terrible massacre and abduction… he doesn’t have to feel bad about not paying her, or pretending she’s a married woman, when he knows damn well she’s a slave. It’s kind of convenient for him to see her as someone who doesn’t feel any pain… It’s like the way they tell you that lobsters don’t feel it when you drop them in the boiling water. What they mean is we don’t have to feel it.

This part of the story tells a sad truth about much of human nature. We are incentivized to see and hear what will benefit us. That is a fact. Which is why we, should spend time working to reprogram our brains so that we can make a primary commitment to the truth. We do that reprogramming by learning to incentivize ourselves against the grain of a culture that will punish us for knowing or speaking the truth. We do this because any time the truth is not a primary commitment, we are greatly at risk of not seeing it, of deluding ourselves… because this is patriarchy, and knowing the truth, our truth, women’s truth… well, that can get you killed.

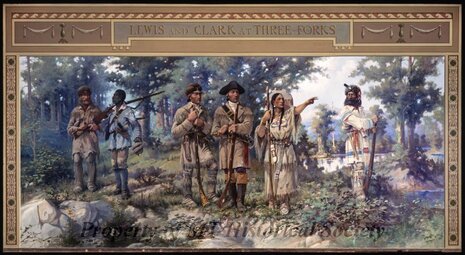

Two enslaved people of color, one of them a female child (depicted here as an adult), with their enslavers-- at least one of whom is a child-raper.

Two enslaved people of color, one of them a female child (depicted here as an adult), with their enslavers-- at least one of whom is a child-raper. Story is everything. It’s the web of synapses we weave to make meaning. As astrologist Caroline Casey says, “Imagination lays the track for the reality train.” It surely does, sisters. And a story is like a line on a railroad… like the Long Island Rail Road or the Staten Island Railway. The story is a route with a destination. We take these stories in when we hear them. We pass them along. We put them in our toolkits for how to live our lives. Story is everything. We have to think critically about the stories we are given. Who is doing the giving and for what purpose? Who is going to benefit from them? We have never had so many stories. Not just books… but Hulu and Netflix and Youtube and cable and movies and podcasts. So many stories… But how many of them tell our truths? Women’s truths? Lesbian truths?

African American author and activist Toni Cade Bambara wrote an essay titled, “The Issue is Salvation,” and in it she says, “I work to produce stories that save our lives.” That’s what we should all be doing. And if we can’t write them, then we can go into uncovering the truth about the ones they hand us.

So here they are… Here are those precious sentences from Meriwether Lewis’ journal… the needle in the haystack… This was on August 15, 1805. Lewis is talking about when the expedition came to the camp where Sacagawea’s people lived… where her tribe was—her family—before that massacre and abduction when she was eleven. And keep in mind, she’s been enslaved this whole time. She’s never been back to her people. This is the first time she’s seeing them in four years.

“We soon drew near to the [Shoshone] camp, and just as we approached it a woman made her way through the crowd towards Sacagawea, and recognizing each other, they embraced with the most tender affection. The meeting of these two young women had in it something peculiarly touching, not only in the ardent manner in which their feelings were expressed, but from the real interest of their situation…”

Two Native American (tribe unknown) girls pose near a tepee - Poley - 1890/1915

Two Native American (tribe unknown) girls pose near a tepee - Poley - 1890/1915 So who is this other fifteen-year-old Shoshone girl who is embracing Sacagawea so ardently? Well, her name was Pop-pank. She and Sacagawea grew up together, and they were at that hunting camp together when the massacre happened and Sacagawea was taken prisoner. Pop-pank had jumped into the river and, leaping like a fish, had managed to get to the other side and escape capture.

And here she was when the Lewis and Clark expedition showed up to try to buy some horses on their way to the Pacific. And here she was seeing again her beloved girlhood friend, Sacagawea… now with a baby and enslaved. And this is what Lewis recorded: the reunion of these two girls—and they were both still girls—embracing each other, tender and passionate at the same time.

Photo by Matika Wilbur, who grew up on the Swinomish reservation in Washington state.

Photo by Matika Wilbur, who grew up on the Swinomish reservation in Washington state. Let us not be fooled by the fact it only warrants two sentences in the journal of Lewis, or that it was only a few stationary minutes out of a journey of hundreds of days and thousands of miles. It is a glimpse into reality, into eternity. It shows up the colonial, patriarchal, misogynist pageant for what it is: an utter sham.

I think of something that 19th century feminist author Charlotte Perkins Gilman said… She said, “Eternity is not something that begins after you are dead. It is going on all the time.” And every now and then we can part the curtain and catch that glimpse. Maybe only a glimpse, but it contains all that we need.

Sisters, let us hold close those two sentences that Meriwether Lewis wrote, not understanding even as he wrote them, because they illuminate the pages of history more than all the rest of the words in his journal.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed