Here’s the Wikipedia condensed version:

In addition he has shared his history of sexual abuse. When he was a little boy, he was sent to a tutor who, according to Brand, "when I got a question right – by way of congratulation – stuck his finger up my arse and felt my balls." He told his mother, who told his father, and the tutoring stopped, but nothing was ever done. When he was a teenager, his father took him on an Asian "sex tourism" holiday, and his father rented a prostituted woman to "teach him to be a man." The father stayed in the room to watch. According to Brand, he was advised to leave his childhood abuse out of the book, but, he wrote, "The reason I left it in was because I thought, if in Chapter Four you see this happen, when in Chapter Twelve, I'm rampaging round having it off with prostitutes, you might see a corollary."

All of this is to say, I believed in Brand's recovery. My first reaction to The Times account was, "Oh, my god! He’s going to own it! He’s going to do something that none of these predators have ever done before! He’s going to model 12-Step accountability, and he’s going to do it on a public stage! He’s going to walk his talk and set an example for the world!"

Russell Brand is no longer a man-boy, mommy-shocker, BBC clown-prince, bad-boy comedian. He’s a political commentator, and an extremely competent one. He has rebranded himself as a whistleblower who is not afraid to take on the government as well as huge corporations. Some consider him the king of conspiracy theories, but, whenever I have watched his podcast, he brings the receipts, posting and citing all of his sources. Impressive. Oh, and he has attracted something like seven million followers… He is actually giving mainstream media a run for the money.

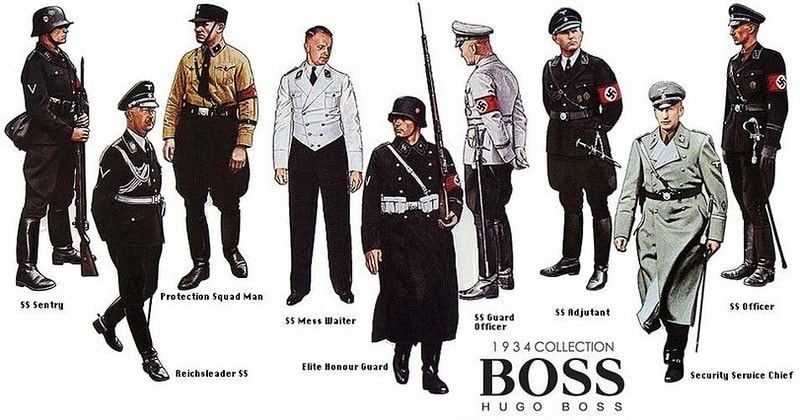

“This environment is not designed for sincerity, you realize… We will struggle if we start bringing sincerity into the situation… I’m glad to grace the stage where Boris Johnson has just made light of the use of chemical weapons in Syria, meaning that GQ can now stand for “genocide quips.” I mention that only to make this next comment a bit lighter, because if any of you know a little bit about history and fashion will know that Hugo Boss made the uniforms for the Nazis, but… and the Nazis did have flaws, but, you know, they did look fucking fantastic…”

So now, Mr. Brand, it is you who are Hugo Boss.

Surely, with all that yoga, meditation, chanting, healthy lifestyle, recovery proselytizing, and especially with all of that whistleblowing, you are going to take responsibility for your actions... After all, you have made millions--millions!—by calling out the sleazy tactics of public figures who are trying to evade public accountability!

Surely, with all of this, Mr. Brand, you are going to show up and own everything… You can’t possibly be that big of a phony and a hypocrite, can you? Surely, now, with two daughters of your own, you can’t model this kind of misogyny? With all your pride about your working-class background, you can’t lean into the classism behind “out-lawyering” your victims? Surely, with two decades of sharing your recovery with the public, now that it’s crunch time, you’re going to “walk the talk,” aren’t you…? Mr. Brand…? Aren’t you…?

And, actually, in anticipation of this kind of exposure, Brand has already been hiring high-power attorneys to threaten former alleged victims who have attempted to go public with their personal stories of rape and predatory behavior. He’s not owning a damn thing. He appears to feel completely entitled to retraumatize these women with legal threats.

Given the opportunity to respond to the allegations before the article went to press, Brand chose not to. Instead, he made his own video on September 16:

“Obviously, it’s been an extraordinary and distressing week, and I thank you very much for your support and for questioning the information that you’ve been presented with… But amidst this litany of astonishing rather baroque attacks, are some very serious allegations that I absolutely refute… These allegations pertain to the time when I was working in the mainstream, when I was in the newspapers all the time, when I was in the movies. And as I've written about extensively in my books, I was very, very promiscuous… Now, during that time of promiscuity, the relationships I had were absolutely always consensual… What I seriously refute are these very, very serious criminal allegations…”

Predation, not promiscuity. Nonconsensual, not consensual. According to the women coming forward, he ambushed women, he assaulted them, he propositioned them in the most intentionally vulgar and demeaning ways. He resorted repeatedly to coercive tactics, including emotional abuse, manipulation, physical intimidation, and force.

After this, he went silent for a week as more women came forward and more criminal allegations were made. And then the hammer dropped: Youtube demonetized his channel. What does that mean? It means he can no longer earn ad revenue off his videos on that platform. (It’s estimated that he was making a million a year off Youtube ad revenue.) In addition, his management company dropped him, his publisher is suspending any planned publications, and the remaining dates on his current tour have been postponed.

"By now, you're probably aware that the British government has asked big tech platforms to censor our online content and that some online platforms have complied with that request. What you may not know is that this happens in the context of the online safety bill which is a piece of UK legislation that grants sweeping surveillance and censorship powers and it's a law that's already been passed."

Yes, every citizen in the UK has reason to be very wary of this legislation. And, yes, Russell Brand has many corporate enemies. He is absolutely posing a threat to mainstream media. He is a consummate showman, and he brings that A-game to his podcast. He makes traditional broadcasters look like sleepwalkers. And his numbers (seven million) are insane. Yes, there are many powerful people who would like to see him taken down.

And, none of that invalidates the allegations by these ten women of decades-long sexual assault, rape, grooming, and predatory behavior... much of which is actually documented.

Back to this second video: Brand directs his followers to move over to the platform Rumble, which will now be his primary platform. (Rumble has not demonetized him.) He outlines the topics of of his future broadcasts: the Trusted News Initiative he referenced earlier, the "deep state" and corporate collusion,” big pharma, media corruption and censorship. At the end, he begs his followers to stay with him as he needs them “now more than ever and more than I ever imagined I would.”

He made no mention of the allegations. It's now all completely about a global conspiracy to shut down his broadcast.

Unquestionably, the stakes are extremely high for Brand. A public amends would be a confession of crimes, and, as of yesterday, he is already the subject of a police investigation. He stands to lose his wealth and spend the rest of his life in prison.

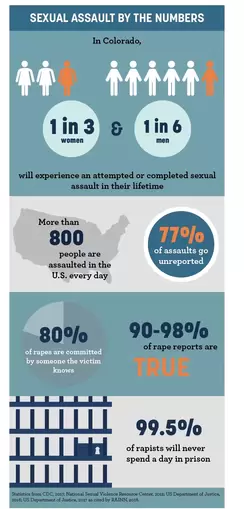

But the stakes are very high for his victims, and these are not just the women coming forward. The victims are also cultural. How many males modeled themselves on Brand, because they saw it worked. They saw him lifted up and richly compensated as a stud. They saw his rape jokes garnering huge laughs. How many women were silenced and disbelieved in the culture for whom he was a figurehead?

The UK has no statute of limitations for sex crimes. Does Russell Brand want to become the test case for challenging that? Does he want to see the UK adopt the kind of time limits for prosecution we have in the US? Because every victim in the US can tell you that these limits only protect the perpetrators. Many criminals move away from the person they used to be when they committed their crimes. Some go on to do good work. Does this mean they are no longer accountable? Brand, consistent with his perpetrations, is now marshaling his forces to set a rape culture precedent in the UK of non-accountability.

I want to say very clearly that Russell Brand is not in recovery from sex addiction. He's taken the playbook of rape culture to a new low in the last two weeks. And if his 12-Step sponsors are endorsing his decision to lawyer-up, to lie, to deny, to deflect, and to do everything he can to discredit his victims, then they are violating their own recovery just as he is violating his.

Mr. Brand, I call you out on your hypocrisy and your ongoing perpetrations. You, yes you, are part of one of the most heinous conspiracies in human history, the conspiracy to degrade, exploit, and subjugate women and girls. Your recovery is a complete sham, and however you attempt to justify your actions to yourself, all of your good works have now been utterly co-opted as part of your criminal cover-up, and they will be remembered in that light. We see you.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed