This was the case with Whitaker's chapter on bipolar. I had covered anti-psychotics, neuroleptics, antidepressants… and I just wanted to move on to conclusions. But my conscience would not let me.

So, here we go: Robert Whitaker on bipolar...

He opens the chapter with a report on the 2008 American Psychiatric Association annual meeting, which he attended. Because of new disclosure guidelines, Whitaker was able to access information about some of the speakers. One example: Joseph Biederman of Massachusetts General who led the way in popularizing juvenile bipolar disorder received research grants from eight drug companies, was a “consultant” to nine of them, and served as a “speaker” to eight. The enmeshment between medical professionals and pharmaceutical companies has apparently become so routine and so widely accepted, no one thinks to ask if this connection might constitute conflict of interest. In fact, failure to have these connections is likely to call into question one's medical credentials. But that's another chapter.

In the past, bipolar disorder was considered extremely rare. In 1955, the rate appears to have been about one in every 13,000. Outcomes were very positive. Whitaker cites a number of studies illustrating that about 50% hospitalized for mania did not have a recurrence. Seems that 70-80% used to end up “socially recovered”… that is, married, working, home-owning. Okay, somewhat heterosexist and capitalist criteria, but at least they were not institutionalized, not on disability payments, not lying on the couch or in bed.

So, what’s the scenario today? One in forty people are diagnosed as bipolar. WHAT? From one in 13,000 to one in 40? And, no, that huge a difference can’t be explained just by saying that medicine has expanded the boundaries of the diagnosis. It has definitely done that, but there is obviously something more significant going on.

Okay… dirty little secret: Studies show that one-to-two thirds of patients hospitalized for bipolar episodes have abused (used?) illicit drugs… specifically stimulants, cocaine, marijuana, and hallucinogens. These weren’t all that popular and available until the 1960’s. So that's part of the epidemic.

But there’s something else… The American Psychiatric Association in 1993 admitted that “all antidepressant treatments, including ECT [electroconvulsive, or "shock" therapy], may provoke manic episodes.” In fact, 20-40% of patients diagnosed with depression convert to bipolar. One study notes that 60% of bipolar patients turned that way after exposure to antidepressants.

Even more sadly, withdrawing the antidepressant that produced the mania will not alter the condition. In other words, antidepressant-induced bipolar disorder is neither temporary or reversible.

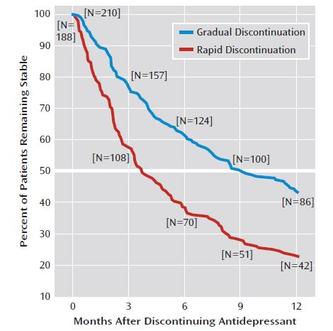

Page after page after page of studies in Whitaker's book illustrate how the antidepressants destroy the symptom-free interludes, which, of course, destroys functionality. Frankly, it makes for depressing reading: “induction of mania,” “induction of rapid cycling,” “increase in number of episodes,” “chronic depression,” “cognitive impairment.” Finally, in 2008, the NIMH released their findings on bipolar treatment: “the major predictor of worse outcomes was antidepressant use, which about 60% of patients received.”

Let me just cut to the chase: In 1955 there were about 12,700 patients hospitalized for bipolar. Today, there are about SIX MILLION adults with the illness, and 83% are “severely impaired.”

And if you have loved ones, as I do, who have been diagnosed and who are on the usual drug cocktails for bipolar, then you can skip the narratives at the end of the chapter. I’m sure the stories will be familiar. Whitaker puts a human face on this tragedy, interviewing patients whose lives illustrate the stages of cognitive impairment and loss of functionality. The descriptions from those who have gotten away from the drugs and managed to survive are telling. One patient notes, “Honestly, it felt like I was waking up for the first time in five years… I had gotten back to being myself again. I felt like the drugs took away everything that was me.”

As terrifying and/or debilitating as episodes of mania or depression can be, it might be helpful for doctors to keep in mind the fact that longterm outcomes for both schizophrenia and manic-depressives are consistently better for patients who are not treated with psychiatric drugs.

Click here to go back to Part I.

Click here to go on to Part 9.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed