Tee was born and grew up in Florida. Her mother introduced her to principles and techniques for making visual art. According to Tee, “I have seldom succeeded in keeping a diary, but I have almost always carried a drawing pad and, since, my eighth year, I have also had a camera.” 1

With a bachelor’s degree in printmaking and painting (with minors in English and history), she went on in 1968 to get an MFA in drawing and sculpture at Pratt Institute. After a few years of teaching and backpacking in Europe, she became attracted to the back-to-the-land movement and communal living. She was also, in her words, sliding into suicidal depression:

At forty-four, Tee recovered memories of being sexually molested at the age of six. .

I am coming to look on my suicidal years (13-29) through the lens of this information, and find, even then, strengths to be drawn upon: the strength of the survivor; the strength of talking which chips away at the killing silence; the knowledge of the value of my own life. It’s mine. I’ve paid for it.3

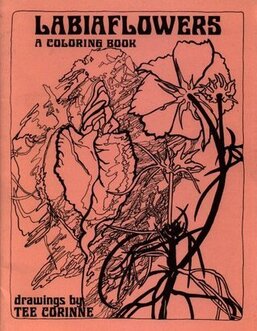

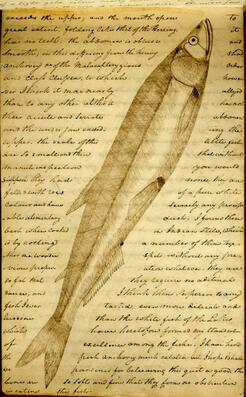

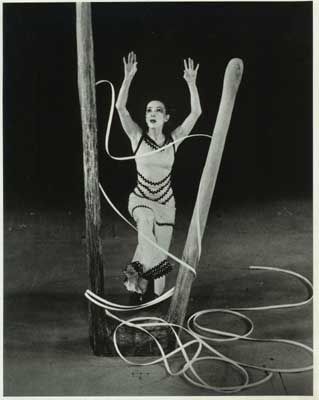

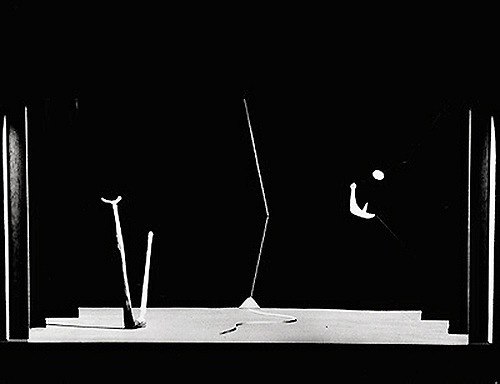

Early version of The Cunt Coloring Book

Early version of The Cunt Coloring Book She became adept at representing lesbian sexuality in ways that would elude the male gaze. In 1982, she produced a series of photographs called Yantras of Womanlove. Concerned with protecting the privacy of her models, she used techniques involving multiple prints, solarization, images printed in negative, and multiple exposures. Tee consistently and conscientiously included women of color, fat women, older women, and women with disabilities as her subjects. Sometimes printers would refuse to print her works and art galleries would refuse to show it. In 1975, she self-published the Cunt Coloring Book, which is still in print today.

My grandmother Mabel died when I was forty, leaving me a suitcase full of five generations of photographs… 5 Somewhere in the process of enlarging and coloring in the old photo images, I began to bring the past and present together, visually and psychically.6

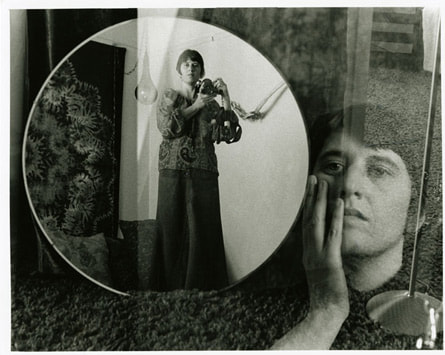

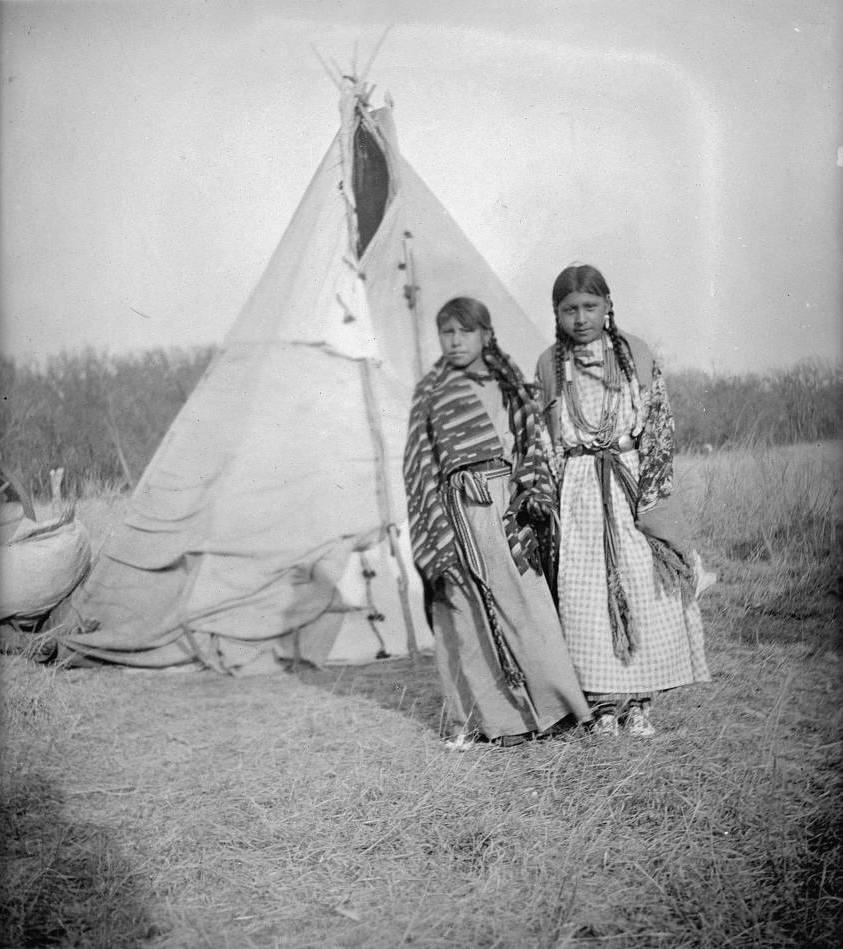

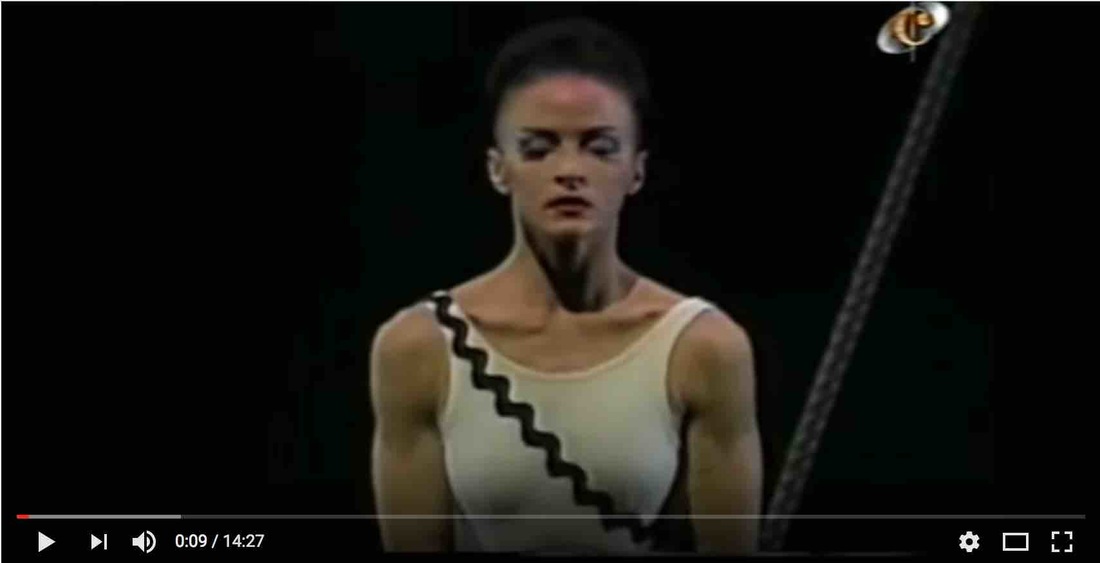

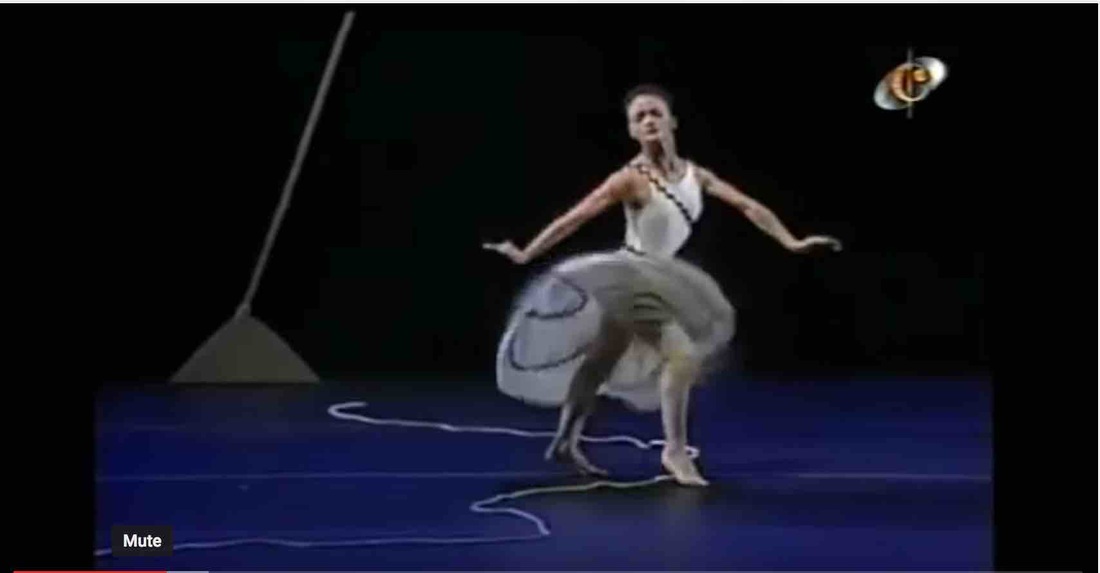

Self-portrait with Beverly

Self-portrait with Beverly In 2004, Tee’s partner of fourteen years, writer and social activist Beverly Anne Brown, was diagnosed with metastasized colon cancer and given a terminal diagnosis. Wanting to use something more immediate than darkroom techniques, Tee learned to use a digital camera and Adobe Photoshop in order to “push the polite boundaries of portraiture.”8 The result is the series “Cancer in Our Lives.”

After the death of her partner, Tee was diagnosed with a rare form of bile duct cancer. On August 27, 2006, she died quietly in her home. She was surrounded by a network of loving and supportive members of her community, who thoughtfully maintained a weblog in order to keep Tee’s wider, international community informed about her health.

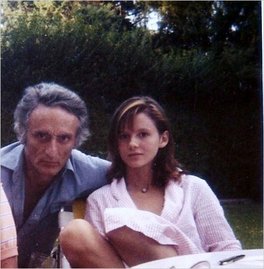

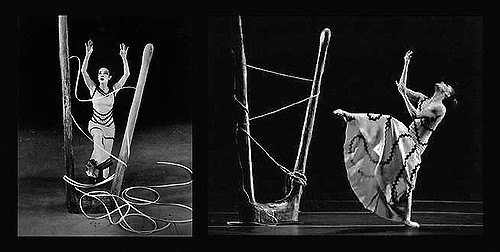

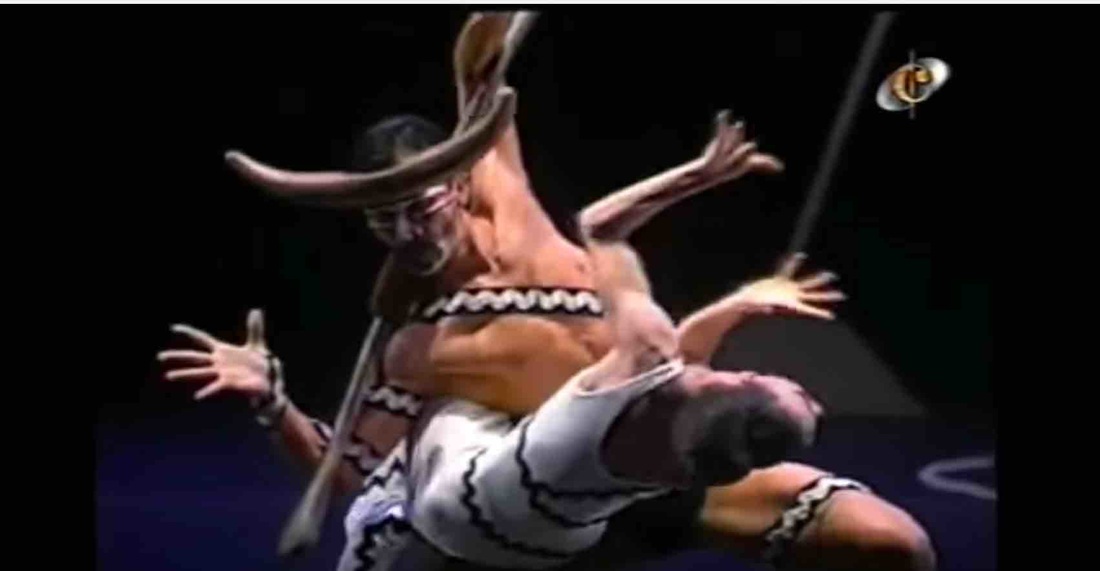

Woman in Wheelchair with Able-bodied Lover by Tee Corinne

Woman in Wheelchair with Able-bodied Lover by Tee Corinne If I look inside me, talk to the child within who, after all, is the one who originally wanted to be an artist, I find that she almost always knows how she wants my work to look: “Beautiful, in a big and powerful way.”9

Those words could stand as her epitaph. Tee, you will be missed.

1. Tee Corinne, “Personal Statement,” http://www.varoregistry.com/corinne/pers.html

2. Tee Corinne, Family: Growing Up In an Alcoholic Family, (North Vancouver, B.C: Gallerie Publications, 1970), p. 3.

3. Ibid, p. 9.

4. Tee Corinne, interviewed by Barbara Kyne, http://www.queer-arts.org/archive/9809/corinne/corinne.html

5. Corinne, Family, p. 7.

6. Corinne, Family, p. 13.

7. Tee Corinne, Riding Desire, (Austin, Texas: Banned Books, 1990), p.viii).

8. Tee Corinne, “Colored Pictures” from “Cancer in Our Lives,” http://www.jeansirius.com/TeeACorinne/Colored_Pictures/

9. Corinne, Family, p. 13.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed