What does that mean? From her perspective, it means accepting that denial can be a natural and helpful part of living. Denial can enable us to keep up with the functions of daily life in the face of fear or grief that might otherwise overwhelm us. No doubt, our capacity for deploying denial is some kind of neurophysiological adaptation designed to aid in our survival and the preservation of the gene pool. It may have been the case that the primates the most adept at denial lived the longest and propagated the most. Acceptance of denial may be acceptance of Darwinian truths hardwired into our DNA.

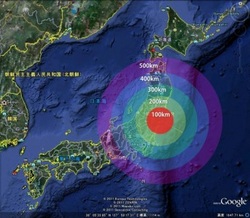

But when I heard the expression, I was not thinking about hospice. I was thinking about Fukushima. I was thinking about the disaster in Japan which still has no end in sight, which is still fraught with possibilities of ongoing, uncontrolled nuclear explosions. I was thinking about the tremendous amount of water which will need to be pumped into the damaged reactors to prevent these explosions, and the as-yet unanswered questions about the disposal of those thousands of tons of highly radioactive water. I was thinking about the radiation which has now gone around the globe and which continues to spew into the atmosphere and seep into the ocean every day as a result of this ongoing catastrophe.

Denial. And now the acceptance of denial.

On March 11 and 12, I had been panicked. Three decades earlier, I was part of a global, anti-nuclear movement. I had been arrested for occupying a nuclear power plant—if you can call leaping into the arms of the police an occupation. With my fellow activists, I had made a study of the industry. We understood the tactics, could spot the rhetoric, sniff out the lies. On March 11, I understood much about what was happening—with multiple, core-reactor meltdowns; with the power behind the cooling systems not only knocked out, but knocked out for days and possibly weeks; with cracked containment pits; with multiple bomb-like explosions. I understood that this was the worst disaster and the most serious threat to life that has ever occurred on this planet... and with no end in sight.

In the world of the jungle, terror is incentivized. Experiencing terror saves one’s life. In a world with scenarios of nuclear holocaust, terror is not incentivized. Denial is. It becomes an attractive option in the face of helplessness and overwhelming doom, of unthinkable consequences for millions of people, for thousands of years. Denial conditions us to believe reassurances without questioning source or motive. Denial enables us to function as if nothing has changed.

I am in this denial now, and it is a great relief compared with the terror of March 11 and 12. The world has not ended. Yet. And that word “yet” appeals to my biology… the “acceptance of denial.” The patient is dying. There is nothing we can do. There is no point in dwelling on it. The best thing to do is go on with our living. For now.

Is this really what it comes down to? “Not with a bang, but a whimper…” Or, not even the whimper?

We have become an increasingly visual culture. I know this, because I am a playwright by trade, and playwriting is an aural art form. People used to say they were going to “hear a play.” Fewer than one fifth of Shakespeare’s audiences could actually see the stage. There is a limited arena for action on the stage, and without special effects, the physical drama is usually embarrassingly bogus. In theatre, the drama is in the language—in the impassioned speeches, in the verbally violent confrontations, in the seduction of argument. As a playwright, I am acutely aware of how theatre has been left behind, like some kind of cultural oxbow lake, as the river of pop culture has moved over, carving out new channels in visual media: film, TV, DVD, Nintendo, 3-D movies, Youtube, Wii, etc.

And the more visual the culture, the greater our disconnect. Why? Because when it’s visual, it’s about appearances. The symbols begin to usurp the substance they are supposed to represent. Thinking, and especially deep, radical, and independent thinking becomes short-circuited as the gaze is directed by the ever-editorializing lens of the camera.

This is the problem with radiation. It is not visible. It can’t be felt or tasted. It has no odor, no texture, no temperature. It’s not as if Fukushima is being covered with ashes or buried in lava. It’s not as if there is a sulfurous, unbreathable gas hanging over the town. The sun still shines, the birds sing, and the flowers bloom. People have to be prevented from entering the zone around the reactors. People have to rely on readings and reporting from experts and agencies to tell them when they can drink the water.

And, as I said, denial has become accepted and acceptable. Because denial is natural in a situation like this, and especially in a culture so heavily oriented to the visual.

The ubiquitous spiritual systems of indigenous peoples point to the fact that ongoing consciousness of the unseen is native to our evolution and our biology. Had we not colonized our senses, we would have understood the blasphemy of splitting the atom, of creating a deadly waste material of which we could not dispose. We would have known that we were arrogating to ourselves the powers over life and death that should never belong to one species. We would have known that what we were doing was displeasing to the spirit world, constituting a profound violation of the sacred.

Nuclear Bomb Testing

Nuclear Bomb Testing "If one had to name one quality as the genius of the patriarchy, it would be compartmentalization, the capacity for institutionalizing disconnection. Intellect severed from emotion. Thought separated from action. Science split from art. The earth itself divided; national borders. Human beings categorized by sex, age, race, ethnicity, sexual preference, height, weight, class, religion, physical ability, ad nauseum. The personal isolated from the political. Sex divorced from love. The material ruptured from the spiritual. The past parted from the present and disjoined from the future. Law detached from justice. Vision dissociated from reality."

I derive hope from the fact that it is possible to recover an apparently innate reverence for the unseen. I take comfort in this. I understand how I am incentivized by a corporate culture and by my own biology to deny the full horror of radioactivity. I accept that. I accept my denial about Fukushima. I accept that this denial may even be natural. But I know that it was once in my ancestral biology to experience rich rewards from sensing the unseen spiritual essence of life and to find joy and peace in honoring that spiritual essence, in being a part of it, in protecting it and cultivating it in myself.

And because I know this, I choose to believe that this sensing of spirit can be recovered—uncovered, dis-covered, and revivified. And this spiritual seeing-of-the-unseen, unlike Fukushima, is powerfully incentivized… by faith, joy, and even ecstasy. It results in tangible enhancement of quality of life, of self-esteem, of sense of belonging. It also results in the reverence that would have prevented the splitting of the atom in the first place, and this reverence holds the potential to prevent the building of new nuclear reactors.

This attention to the cultivation of my spiritual sense is the most focused and effective and political response I can make to what is happening to the ocean and to the land and to the air and to all the forms of life on this planet.

Albert Einstein said, “The splitting of the atom changed everything except man’s mode of thinking.” I am choosing to believe and endeavoring to prove that he was mistaken.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed