Never let a jealous homophobe edit your work.

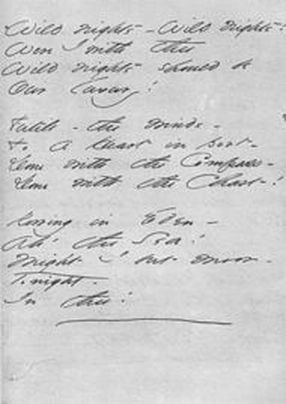

Never let a jealous homophobe edit your work. Most of the dashes were edited out of Emily Dickinson’s poems when they were first published in 1890. The editors, Mabel Todd Loomis and Thomas Higginson, also “regularized” her spellings and word usages. The poems were not “un-edited” until the 1950's.

Mabel Todd Loomis also suppressed all references to Emily’s lesbian relationship with Susan Huntington Dickinson, Emily’s sister-in-law and next-door neighbor. There is no mention of Susan in the Letters of Emily Dickinson, published by Loomis in 1895—even though Emily’s correspondence with Susan is voluminous, spanning four decades and including drafts and notes about the poems as works-in-progress. (Loomis was the mistress of Austin Dickinson, Emily’s brother and Susan’s husband.)

The letters were not published until 1998.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

By Emily Dickinson's Dash

I am Emily Dickinson’s dash—the hand-off in a relay race. I am “Heads-up!”—“Your turn!”—“Last tag!” I indicate a synapse. I spark the gap, up the ante, pass the baton. I am the very first thing that had to go, when they decided to publish Ms. Dickinson’s work—but, no!— I am the second. The first, of course, were the poems that made reference to Emily’s passion for Sue Gilbert.

The dash is an elevated blank, if you think about it. It is an appropriation of silence. It indicates an intentional—defiant?—ambiguity. It is the author’s evasion of the literary house detectives. What cannot be named can be synapsed around, and after a while, there is—there will be—a connection.

Virginia and Gertrude were dashing women, also. But Emily was the only one who could dash her brains out. I am the fragments of that broken plank in reason. I didn’t come cheap.

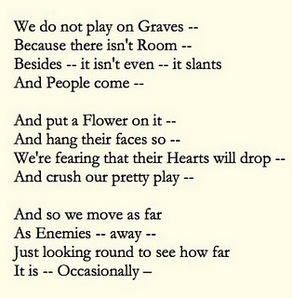

Emily's dashing love poem to Sue Gilbert

Emily's dashing love poem to Sue Gilbert Ah, Sue—How to measure the distance between Sue Gilbert’s kitchen and Emily’s bedroom window? No dash in the world could bridge that gap, but I was the gesture. And—yes, let it be said—I was also the taunt: “See what I can do.” Because everyone could see what Sue could do. She could procreate. She could delegate. She could regulate.

Emily's dashing love poem to Sue

Emily's dashing love poem to Sue But Emily, Emily—one-trick-pony!—Emily could synapse. Sly Emily. Shy Emily. Gay and dashing Emily. Emily was quantum, where Sue was algebraic. Emily was possibility; Sue was probability. Where you locate Emily in time—the “onset of Eternity”—you cannot graph her coordinates in space. When you pinpoint her in “Amherst,” it’s “Good Morning—Midnight—.” I did that for her. I am the quark of punctuation.

What started as morse code for Sue ended up a cryptogram. Clumsy dyke, Emily only wanted to bridge the gap between houses. Naive Emily! Little did she know those houses were galaxies apart, and the little dash—the wistful open palm—(my house or yours?)—was the password through language to the boundaries of thought. And she went there. And every time she did, a part of her never came back. And between what jumped the fence to Sue’s house, what fell through the floor of reason, and what bled out between synaptic gaps—what lived upstairs in her father’s house became more and more translucent—a doppelganger. Emily’s body became the punctuation they craved so much for her. Her body was the period that anchored a life sentence. It was the comma of the essential—for women, anyway—subordinate clause. It was the quotation mark of other people’s ideas, the semi-colon caution light before we can proceed through the intersection. She was all punctuation when she died. Her spirit had fled long ago in great mad dashes. And Sue Gilbert was left holding the memories, which, finally, were containable after the dashes had been deleted.

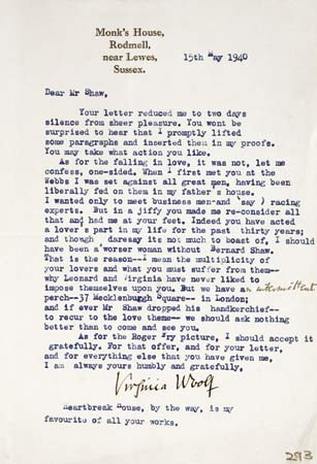

Virginia Woolf dashes off a letter.

Virginia Woolf dashes off a letter. Virginia reserved her dashes for letters. They could be mistaken for haste. Her readers had an out. Gertrude alternated with ellipses. She invited sighs—handrails. There are absolutely no sighs associated with the dash. No trailings-off, no “ah, well . . . another day, perhaps . . .” No “if only . . .” where Sue Gilbert was concerned. “If only’s” are for novelists, not poets. Poets are about precision— or nothing at all. When Emily failed to finish a sentence, it was an act of courage, not cowardice. I was her springboard into eternity.

“Think like me and see where it gets you.” All dressed in white, talking through closed doors. No need to open them when one can trans-port—literally—with the dash. And the white? Absence of color, that “Element of Blank”—traveling clothes for the synapser? What is the opposite of mourning? Surely not life—That only leads back to death.

The opposite of death is the dash. But it will kill you.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed