It was revised and published as "The Case for Marlowe as the Bard,” Harvard Gay and Lesbian Review, Vol. 5, Number 4., Cambridge, MA.

Debate about the authorship of the Shakespeare canon has entered the era of post-modernism and electronic media with mock trials, interactive seminars, moot court hearings, caucusing at international conferences, websites, and PBS Frontline specials. The questioning of the authorship, however, dates back to 1728 when the issue was first raised in print by one Captain Goulding in his "Essay Against Too Much Reading." In the intervening centuries, many theories have been put forward, and the roster of potential candidates for authorship includes Sir Francis Bacon, Ben Jonson, the 6th Earl of Derby, Christopher Marlowe, Sir Walter Raleigh, Thomas Nashe, Robert Greene, Thomas Lodge, the Earl of Rutland, Sir Edward Dyer, Queen Elizabeth... and a "Learned Pig."

The most recent controversy centers around Edward de Vere, the 17th Earl of Oxford, whose name was first entered in the lists by British schoolmaster J. Thomas Looney in 1920, and whose claims have been most recently advanced by columnist Joseph Sobran in his book Alias Shakespeare: Solving the Greatest Literary Mystery of All Time (Free Press, 1997). The "Oxfordians" build their case on the recent discovery of de Vere's Bible, with annotations that correspond to various passages from the plays, and on similarities between de Vere's experiences and plot lines from certain of the plays, most notably Hamlet. As with every authorship theory, there exists a substantial body of scholarly refutations.

I am obviously not in sympathy with the cause of the Oxfordians, but, like many women authors before me --- including Muriel Spark, Clare Booth Luce, Helen Keller, and Daphne du Maurier --- I have come to question the traditional wisdom that attributes the canon to the actor-householder William Shakespeare. In adding my voice to the debate, it is my hope that my disputants will heed the words of him whom we have come to praise, not to bury and "do as adversaries do in law/ Strive mightily, but eat and drink as friends."

It begins with Aunt Mary, the family eccentric. A large, athletic woman, Mary had joined the "hut boys" of the Appalachian Mountain Club in the 1920's to blaze trails and to stock cabins in the White Mountains. A radical thinker, she had broken with her father's conservativism to take up the cause of Labor in the 1930's. In 1964, at the age of fifty-five, she returned to Wellesley College to finish a degree program begun thirty years earlier. After graduation, she had enrolled in a Master's program at Connecticut College, where she stubbornly devoted the next three years to writing a thesis that her advisors warned they would never approve. That was my Aunt Mary, quite contrary.

Mary, Mary - Quite Contrary

Mary, Mary - Quite Contrary And it was there the thesis sat, gathering dust for several years, until the evening my research on a nineteenth-century lesbian actor drove me in search of information about Shakespeare. That's when I remembered the book.

Chained books at the library at Wells Cathedral, dating back from the 15th century

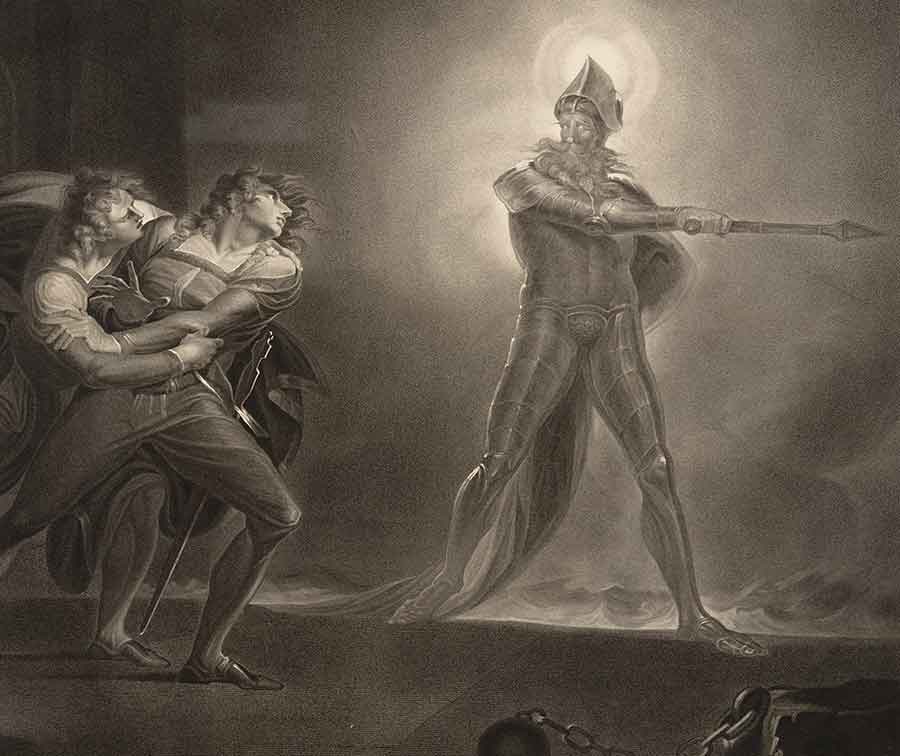

Chained books at the library at Wells Cathedral, dating back from the 15th century Like the ghost in the play, Marlowe had returned in spirit to expose a crime that had been perpetrated against him. He had come back to reveal how his kingdom - and such a kingdom! - had been usurped by one not worthy of the title. The usurper, of course, was William Shakespeare.

William Shakespeare, that greatest of all dramatists in the English language, is the figure against which Western playwrights measure ourselves - and fall miserably short. The facts of his life are the stuff of legends. With no opportunity for education beyond the local grammar school, he had somehow achieved a university-level proficiency in Greek, Latin, and the classics. Even in an era of public libraries, this would be an impressive feat, but for an author who had lived at a time when there weren't even any published dictionaries, it challenges credulity. The texts for the classics were not in general circulation, and the books he would have to have read were cloistered in the private libraries of very rich men or chained to the desks at Cambridge and Oxford, where none but students and professors could access them.

Artist's conception of Shakespeare reciting Hamlet to his family

Artist's conception of Shakespeare reciting Hamlet to his family

Perhaps the most daunting aspect of the Shakespeare legend is his reputation for writing the plays "with scarce a blot," the manuscripts delivered to the printer apparently containing no editing, rewrites, or even minor corrections. It would appear that William Shakespeare lived and breathed and had his being in perfect iambic pentameter.

So here had been my role model for playwriting - the solitary genius with the time and inclination to raise a family, the full-time writer with the initiative to run a busy theatre - William Shakespeare, the man who traveled by astral projection, who learned by osmosis, who existed simultaneously in parallel universes, and who channeled his plays through automatic handwriting.

Virginia Woolf wrote of being hounded by the Victorian specter of an "angel in the house," an unwanted alter-ego who continually tried to censor her unladylike writing. I, in my work as a feminist playwright, have also been plagued by a demon - this fiend of a bard from Avon. Where Virginia Woolf chose to kill her tormentor, I have endeavored to compete with mine: If Shakespeare had run his own theatre company, then so would I. If Shakespeare had produced his own plays, then so would I. If Shakespeare had performed in and toured with his own productions, then so would I. If Shakespeare had been able to meet the demands of family life, then so would I. And if Shakespeare could write one and a half plays a year while holding down a full-time job and commuting, could I, a writer of non-poetic drama, be expected to produce any less?

All of my efforts to emulate my role model only demonstrated how far short I fell of my ideal: My domestic life was a disaster, the petty politicking within the theatre company drove me crazy, acting and directing and producing and touring and playwriting produced a disorder akin to multiple personality syndrome, and the pressure to write even two plays a year was overwhelming. Finally, after years of this insanity, my body had enough sense to go on strike, and I collapsed.

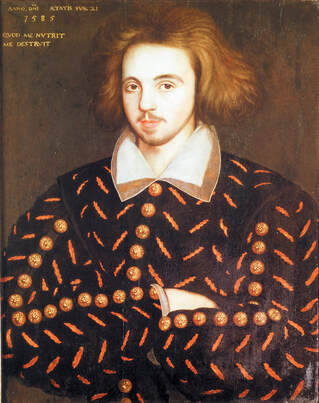

Corpus Christi portrait associated with Marlowe

Corpus Christi portrait associated with Marlowe In addition to the daunting record of achievement, there was another angle to the long shadow cast by the Shakespeare legend. As a very public lesbian-feminist playwright, I was forever in trouble: threats from the local homophobes, shunning by straight women and closet lesbians, eviction and boycott from gay men, slander from lesbians in coalition with all of the above, attacks from poverty-class lesbians for being middle-class, neglect from middle-class lesbians for espousing working-class causes, lawsuits with educational systems, trashings in the press, systematic exclusion from production and publication opportunities, and --- most painful of all --- sabotage from the members of my own theatre company. Why couldn't I be more like the easy-going William Shakespeare, who was apparently respected by his peers, accepted as an equal by the members of his theatre company, loved by his family, generously supported by his audiences and patrons, and well thought of by his community? He had even scored a coat-of-arms, the sixteenth-century symbol for "having arrived."

The night Marlowe appeared to me in my loft, I discovered the secret identity of the author of King Lear, Romeo and Juliet, Hamlet, and Othello. The world's most famous playwright was not only rumored to have been a screaming queer, but had left England under threat of death for his heresies. He had been arrested and incarcerated. Even after the news of his death, his name continued to be vilified in the press and from the pulpit. Kit Marlowe, mon frère.

So, what's the story? The subject could fill a book, and, in fact, already has. In brief, here's the synopsis:

Sir Thomas Walsingham

Sir Thomas Walsingham Marlowe, born in 1564 (two months after the birth of the actor William Shakespeare), was the son of a cobbler. He had been able to obtain scholarships first to a prep school and then to Cambridge, evidence that his intellectual gifts had been recognized at an early age. During his years at Cambridge, Marlowe became involved in Her Majesty's secret service, and when the university attempted to withhold from him his Master's degree on the grounds of excessive absenteeism, the Queen herself intervened with a message from her Privy Council: "... it was not her Majesty's pleasure that anyone employed as he [Marlowe] had been in matters touching the benefit of his country should be defamed by those ignorant in the affairs he went about." Needless to say, Marlowe received his degree.

Instead of taking the religious orders which might have been expected under the terms of his scholarships, Marlowe had gone to London, where his first play Tamburlaine had been a brilliant success. At this time, his patron was Thomas Walsingham. Walsingham's cousin was Secretary of State, and both Thomas and his young protegee moved freely in court circles. Marlowe joined a group of heretical intellectuals who centered around Sir Walter Raleigh, and he was hailed as the most gifted and original playwright of the age.

Thomas Kyd

Thomas Kyd Heresy was a serious charge, and heretics were still being burned at the stake in England. A week later, on May 20, Marlowe was arrested at Walsingham's estate, but his influential friends managed to arrange for his bail --- on the condition that, until the date of the hearing, he report daily in person to the Privy Council. This would effectively prevent Marlowe from leaving the country.

During this time a formal charge of heresy was entered against him by one Richard Baines, a government informer. Baines claimed that "almost into every company he [Marlowe] cometh, he persuades men to atheism, willing them not to be afraid of bugbears and hobgoblins and utterly scorning both God and ministers."

- "That the first beginning of Religion was only to keep men in awe."

- "That all Protestants are hypocritical asses."

- "That if he [Marlowe] were to write a new religion, he would undertake both a more excellent and admirable method, and that all the new testament is filthily written."

- "That all they that love not Tobacco and boys were fools."

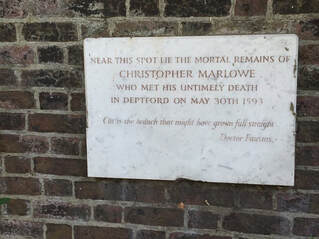

Until the nineteenth century, Marlowe's death had only been an historical rumor with no details as to the date, place, or circumstance. Then, in 1820, the burial record was found in Deptford. It read, "1st June, 1593, Christopher Marlowe slain by Francis (sic) Frizer."

Dr. (John) Leslie Hotson

Dr. (John) Leslie Hotson According to the official report, Christopher Marlowe had been socializing all day in a rented room of a private residence (not a tavern!) with three of his secret service buddies, men who were also in the employ of Thomas Walsingham, Marlowe's patron. Allegedly, there had been an argument over the bill, Marlowe had attacked one of the men, Ingram Frizer, and the man had reacted in self-defense, fatally wounding Marlowe in the face with a dagger.

These are the facts of Marlowe's "murder," a murder which occurred within days of his hearing before the Privy Council on charges of such a serious nature that even his wealthy patron would not have been able to save him from torture --- and the possibility of his naming other "heretics" --- and execution.

If the murder had been staged (as the circumstances would suggest), with the substitution of a corpse with a mutilated face for the body of Marlowe, and if Marlowe had been allowed to escape from England to live in exile, this would certainly explain a number of things.

Artist's conception of the murder of Christopher Marlowe

Artist's conception of the murder of Christopher Marlowe If Marlowe did escape, it would explain the familiarity with and interest in foreign settings for the plays. It would also explain why the manuscripts received by the printers were letter perfect: A copyist would have been hired to transcribe all of them in order to prevent Marlowe's handwriting from being recognized. It might also explain the unusual and generous bequest to a copyist made by Thomas Walsingham in his will.

If Marlowe had escaped, it would explain how the author of the plays knew so much first-hand about working-class life, about the inside of jails, about court intrigue and customs, about Cambridge, and about exile. It would explain the author's extensive knowledge of the classics. And if the author had been living in exile, away from his family and friends, away from the theatre, away from the country where his language was spoken, it would explain how he acquired the solitude, isolation, and leisure that every other creative author in the history of the world has required in order to turn out works of comparable genius.

Juliet believing that Romeo is dead, when he is not.

Juliet believing that Romeo is dead, when he is not. It would explain the sonnets about separation and, if Marlowe was indeed gay, it would explain the sonnets about gay love. As a rule, the Shakespeare plays do not treat marriage kindly, and when there is a stable, loyal relationship, it is inevitably between members of the same sex, especially between two men. (When camaraderie is depicted between a man and a woman, frequently the woman is passing as a male, or - as in Taming of the Shrew - both partners are actively engaged in mocking and subverting the heterosexual paradigm.)

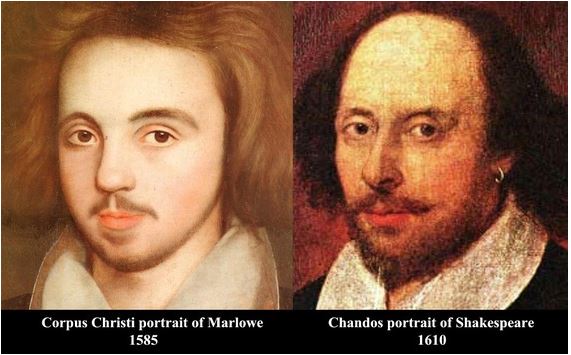

Then there is the "Corpus Christi portrait," dated 1585, and discovered during renovations at Corpus Christi College of Cambridge in 1952 or 1953. One account says that it was discovered in the walls of the room above the one occupied by Marlowe 370 years earlier. Is it a painting of Marlowe? It could be. Marlowe would have been a young man of twenty. Certainly, the subject is opulently dressed for a scholarship student, but there is evidence that in 1584 Marlowe began receiving "significant additional income from an unknown source" [Wikipedia]. In any event, since 1950's the painting has become firmly associated with Marlowe.

They appear to me to be portraits of the same man, twenty years apart. The configuration of the lips, the fly-away hair, the eyebrows, the thinning hair over the forehead that's already apparent in the younger portrait. One final word: The Corpus Christi painting carries the inscription: "Quod me nutrit me destruit," which translates to "That which nourishes me destroys me."

______________________________

Aunt Mary's sculpture

Aunt Mary's sculpture As a child, I remember discovering one of Mary's sculptures up in my grandmother's attic. It was a stunning female nude, and I had asked my mother why her sister had never told me she was an artist. My mother explained that with Mary's passion for great art, she had decided it was better to quit than to run the risk of turning out inferior work.

Aunt Mary had aborted her career without even giving herself the chance to develop. I can't help wondering how much the censorship of information about women artists and the inflated myths of male artists, like the legends surrounding the actor William Shakespeare, had contributed to her unrealistic expectations and subsequent demoralization. And I also can't help wondering if her return so late in life to academia, with her hopeless quest for the acceptance of her heretical thesis, was not the final act of a tragic patriarchal drama in which her own monarchy had been usurped by a pretender.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed