CG: Well, not to keep readers in suspense, we were frustrated in our respective efforts to confront racism and homophobia. And, in fairness, it was fifteen years ago.

JL: And yes, I had written Who Will Sing for Lena? around that time and since then, it has done fairly well in various places. But the film was a totally different project; it was, of course, related to Lena Mae Baker, but not at all related to my play. Believe it or not, the two are very different perspectives, even of Ms Baker. But as I have always said, Lena helped me to write my play and I told it the way she told it to me.

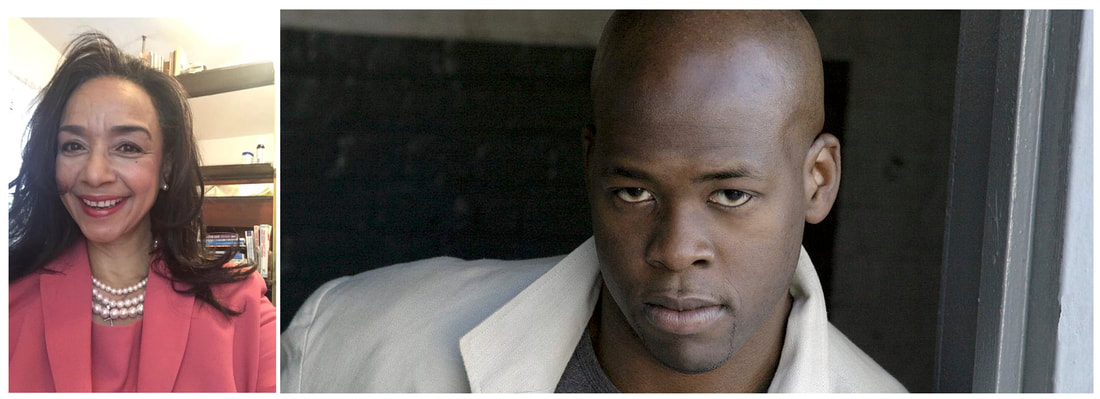

Dr. Janice Liddell

Dr. Janice Liddell JL: Wow, coming from you as a brilliantly successful playwright yourself, that is quite an endorsement. I am glad it affected you because, truth be told, it affected me even as I wrote it. But I’m sure you know that experience—of being carried away by the work as though you are channeling it. That’s a bit how it was for me.

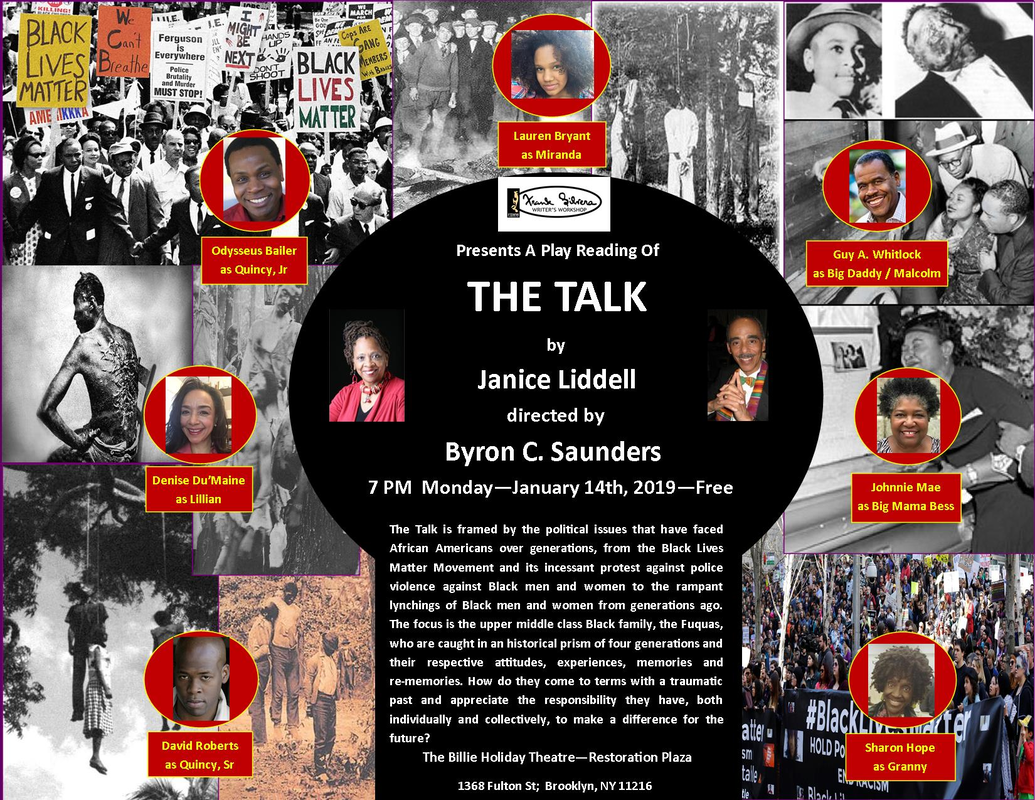

CG: So… “the Talk”… First off, before we get into talking about the play specifically, can you tell us to what “the talk” refers?

JL: This is a highly successful Black middle-class family and in their eyes, as in the eyes of many “highly successful Black middle-class families,” their success has resulted from them pulling themselves “up by their bootstraps.” They would likely never admit they went to university on an Affirmative Action program (as did I), for example. Additionally, they desire to separate themselves from the more “common” element of Black folks—separate themselves in every way they can. In fact, they tend to look down on the experiences of Black folks who, in their middle-class eyes, are financial, intellectual, educational, etc. failures in life. These parents have tried to shelter their children from these “failures” and serve as models for the successful route of Black people from poverty to wealth; from the ghetto to the suburbs. However, their middle-class Black children are highly influenced by the world outside of their “burbs.” Quincy Jr. is in college with youngsters from all walks of life; Miranda is so attached to her tablet and research on it that there is nothing that gets by her. The children and their parents are in totally different “realities”—and at this point, never the twain shall meet.

In earlier drafts, Quincy Senior was a rather cardboard cutout—a one-dimensional character who demonstrated success, but seemed a bit unreal. I had to give him some flaws and some failings within in his own context. Additionally there were three children in the original draft, but one of them just wrote herself right on out. She was so unnecessary. One of the difficulties I had with the play was infusing a little levity. I didn’t want it to be a burden throughout for an audience. I had read about the “blue letter” episode and thought it might be a bit of comic relief. The end of the play gave me pure fits—how to draw all those pieces together was a challenge…that dreaded denouement. I do hope it’s all believable.

Sharon Hope as great-great grandmother

Sharon Hope as great-great grandmother CG: So you have a production coming up in January in Brooklyn… MLK Day, right? What’s going on with that?

Byron Saunders, Director

Byron Saunders, Director CG: I would like to see this play done in every community… Maybe see about getting some touring productions that are funded to go to different cities. What are your plans for marketing the work, and do you have any plans to film it?

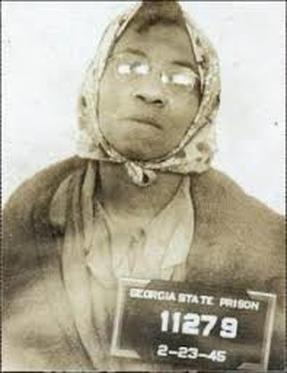

Lena Baker, subject of Who Will Sing for Lena?

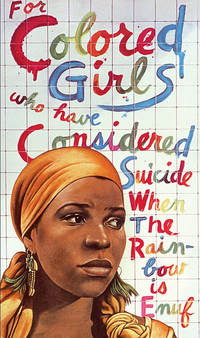

Lena Baker, subject of Who Will Sing for Lena?  Ntzoke Shange's watershed play about the lives of young Black women

Ntzoke Shange's watershed play about the lives of young Black women JL: Well, I have about six completed plays, including one for children, so I guess you can say I actually have “a body” of work. All of my plays are located on the New Play Exchange (shout out for NPX!). So anyone can review them and contact me if they are interested in seeing a full script. Putting them on NPX might be called my one passive stab at marketing (lol). Regarding being an African American playwright, I can’t speak for African American playwrights generally, but of the ones I know up close and personally, it’s rough out here. What I and my playwright friends lament about is that there are so few theatres interested in Black plays or plays written about the Black experience. And the ones that exist seem to want recognizable names or plays that have already proven their value. There are a few stars—August Wilson, of course, and a few others like Lynn Nottage, Suzan Lori Parks, the recently deceased Ntozoke Shange and a precious few others. So, I do think it is difficult being an African American playwright, especially an African American woman playwright primarily because our experiences are just not considered universal enough to give theatres confidence that their audiences will turn out for them.

My experience as a playwright is further complicated by two factors: one is that I am 70 years old. I wrote my first play when I was 50--Hairpeace –and it earned a spot at Atlanta’s Horizon Theatre’s New Plays for the New South Theatre Competition and Workshop. I loved the writing experience, the workshopping and hearing my words on a stage; I had found a new love! But I’m a senior citizen and nobody knows my name. Further, the second factor connects directly to that one--I didn’t come through an MFA program or some other training ground that connects one to the powers that be in the field. I learned the art and craft of writing plays from reading plays and teaching plays. I was an educator—an English professor, chair of an English Department, a university administrator and wrote plays in my “free-time” so as far as the theatre community is concerned, I guess I haven’t earned my stripes in the field; maybe I don’t even exist. Actually, it took me a decade and three or four plays before I could call my own self a playwright, so I guess I shouldn’t be surprised by the perceptions within the theatre community. I believe my work is good and at this point, I guess I’ve been satisfied with that comfort. When my work is produced, I actually feel I have hit a huge bonus. However, thanks to Byron and now you, I must admit, I’m pretty excited about The Talk and its future.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed