Yes, it’s true that lesbians in the spotlight have historically needed to disguise their orientation. The penalties for deviance from the heterosexual template have been swift and severe. This was especially true for women athletes, who, by the very nature of their achievements, posed a challenge to the tenets of femininity. (They had muscles and they were competing!) The media, and sometimes even the fans, were all too eager to find some excuse to invalidate the achievements of a threateningly ambitious and aggressive female athlete. For homophobes, uncovering a lesbian identity provided a comforting assurance that the athlete could not have been a “real woman.”

The Diesel Daisies at the Gay Games

The Diesel Daisies at the Gay Games Babe Didrikson Zaharias is a case in point. She was a tomgirl from the get-go, racking up trophies for a variety of sports in high school and even trying out for the football team. Recruited for an amateur basketball team in Dallas while still in her teens, she made such a name for herself, she was invited to try out for the 1932 Olympic track team. In order to get around the three-event limit for individual athletes, Babe’s handlers were allowed to register her as a team, all by herself! In two and a half hours, she won five events (shot put, javelin, long jump, baseball throw, and 80-meter hurdles)—setting a world record in the hurdles and javelin. In addition, she tied in the high jump, setting another world record, and finished fourth in discus. She scored eight points higher than her nearest competition—a team of twenty-two women!

At the Olympics, bound by the three-event limit, she scored two gold medals—breaking her own world records in both, and took the silver in the high jump. During this period, Babe was too focused on winning to give much attention to her image. She appears to have been perfectly comfortable with herself, her only concession to “media spin” having been a misrepresentation of her age. Claiming to be eighteen instead of twenty-one, Babe may have been catering to the public’s acceptance of tomboy behaviors in a girl who is still in her teens, as opposed to their expectations for “young ladies.”

Babe Didrikson

Babe Didrikson Gallico launched his first attack with an article in Vanity Fair titled “The Texas Babe.” In it he made the comment that this “strange… girl-boy child” would have been right at home in a men’s locker room. He used the word “boy” more than a dozen times to refer to Babe, attributing her athleticism to an over-compensation for her inability to attract men.

What Gallico did not mention was that Babe had made a fool out of him. After the Olympics, fellow sportswriter Grantland Rice had arranged a friendly game of golf to introduce Babe and Gallico. (In the days before television, syndicated sportswriters wielded considerable power in making or breaking athletes, and Rice was one of the most influential. He is arguably responsible for the celebrity of a roster of athletes including Jack Dempsey, Babe Ruth, Bobby Jones, Bill Tilden, Red Grange, and Knute Rockne. His support for Babe was a key factor in her success.) Exploiting Gallico’s machismo, Babe challenged him to a footrace in the middle of the golf course, and Gallico idiotically accepted the dare. Needless to say, Babe left him for dead and went on handily to win the game. It was after this humiliation, Gallico began to obsess over the prominence of Babe’s Adam’s apple.

Paul Gallico, Babe's nemesis

Paul Gallico, Babe's nemesis This was 1933. Suddenly Didrikson began to wear hats, dresses, girdles, lipstick, perfume, and nail polish—all the things she used to dismiss as “too sissy.” And within five years, she was married to George Zaharias, a professional wrestler who, according to Babe’s biographer Susan Cayleff, was “was a caricature of manliness: tough, ferocious, powerful... able to take punishment.” His weight would eventually balloon to 400 pounds. Photographed next to George, Babe did appear more feminine. Also, she was now playing golf, refusing to discuss either her previous career in basketball or her Olympic achievements in track, insisting that her sports career began with golf. Amateur golf—and there was no such thing as professional golf for women at that time—was an elite sport, requiring membership in a country club. These were the “ladies who lunch, ” wives of wealthy men or daughters of privilege, and Babe, an immigrant truck driver’s daughter, had to step up her gender game.

Marriage to George Zaharias worked, and the press eased off. So successful was Babe in presenting herself as a traditional housewife, that, several years later when Babe entered a long-term relationship with a woman, the press was willing to characterize the woman as Babe’s “protégée.” According to biographer Cayleff, Betty was Babe’s “primary partner.” A fellow pro golfer, Betty roomed with Babe on the Ladies Professional Golf Association circuit and lived in her home for the last six years of Babe’s life. Whatever George may have thought of this arrangement, he accepted the situation. When Babe was in the hospital dying from colon cancer, Betty moved in with her, pushing the beds together. Babe trusted her to change her colostomy bag, and it was Betty who, at Babe’s request, shaved her legs for the last time.

Betty, George, and Babe

Betty, George, and Babe The response from our first studio production was overwhelmingly positive, but not without reactions to this “outing” of Babe. Was this respectful to her memory? Would Babe have wanted it? And, of course, the smiling homophobia: “What does it matter anyway? Babe was still a great athlete.” Some of the critics who reviewed the play felt a need to talk about George. After all, wasn’t he the great love of her life?

At what point can we recognize that Babe was bisexual—or a lesbian whose marriage may well have been a concession to career-busting homophobia? The larger question is when will the mainstream become so literate about lesbian history and culture that they can recognize and embrace the archetypes and paradigms of the lesbian butch: the aversion to dresses, the achievement in traditionally male arenas, the advocacy for women?

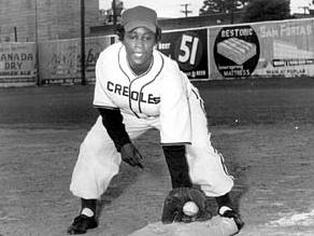

Toni Stone

Toni Stone Toni Stone was a tomboy, but was she a lesbian? She didn’t like girls’ clothes. In her own words, she was “big and sassy.” She dumped her birth name “Marcenia” in favor of one that “sounded more like ‘tomboy.’” Like Babe, she excelled in many sports as a child: ice skating, golf, track, high jump. She was especially passionate about baseball. Her parents, a beautician and a barber, were distressed enough about Toni’s gender deviance that they arranged for her to have pastoral counseling at the age of ten. Fortunately, Toni’s priest was sympathetic and signed her up for his Catholic Midget League… And she never looked back.

Toni had it rough traveling with nothing but men. Not only was she having to deal with Jim Crow laws regarding segregated accommodations, but, as the only female player, she was shut out of the locker room. And she was left to her own devices in terms of dealing with sexual harassment. One of her former teammates narrates a story about Toni sliding into base. The second baseman tagged her by running the ball up her crotch and over her breasts. Toni immediately leaped to her feet and began punching him. Another time, she would take after a harasser with a baseball bat. According to Toni, that man never bothered her again.

Toni Stone in a pubicity shot she regretted

Toni Stone in a pubicity shot she regretted In her biography, there is no record at all of any boyfriends. There is, however, a husband. His name was Aurelius Alberga and he was forty years older than Toni. She married him shortly after she moved to San Francisco, when she was struggling with various jobs—including operating a forklift on the docks—while trying to play professional baseball. Alberga, who is credited as being the first black officer in the US army, began his working life as a bootblack, later becoming a successful realtor and insurance salesman. By the time Toni met him, he owned a Victorian house in Oakland and was well-enough off to support a wife. Aurelius was what was known as a “race man,” having helped organize San Francisco’s NAACP as well as a black Masonic lodge in Berkeley. He was an avid supporter of Marcus Garvey.

It was, to the say the least, an unusual marriage. Toni was twenty-nine and her husband was in his seventies. After the wedding, she moved directly into a bedroom on the first floor, while Aurelius’ bedroom remained on the second floor. Was this a love affair, or was it a companionate arrangement between a progressive, older man, who would be in need of nursing care, and an unusually independent and ambitious young woman struggling to survive in a new city? Did Aurelius recognize her enterprise and her self-determination, seeing something of his own character and struggle in her stories? Was he gay?

Toni stayed married to Aurelius, and she did take care of him in his old age. He lived to be 103. Unlike Babe, no female “protégées” or “housemates” turn up in the historical record. History would have us believe that Toni Stone’s only passion in life was for baseball… and a man old enough to be her grandfather. I remain a skeptic.

In an interview with the Lexington Herald-Leader, Stoni said, “I loved my trousers, my jeans. I love cars. Most of all I loved to ride horses with no saddles. I wasn’t classified. People weren’t ready for me.”

And perhaps we still aren’t. I am wishing that lesbian athletes, then and now, could all have time capsules, where they could safely store the truth about their lives, including the truth about the ones they loved—the women who stood by them through so much oppression, and whose loyalty has been rewarded with obscurity, so that we historians and cultural workers would not be faced with the closeted record of their lives and perpetual questions about how best to honor the memory of women who were compelled to live a lie.

Recommended biographies:

Ackmann, Martha. Curveball: The Remarkable Story of Toni Stone the First Woman to Play Professional Baseball in the Negro League. Lawrence Hill Books, 2010.

Cayleff, Susan E. Babe: The Life and Legend of Babe Didrikson Zaharias. University of Illinois Press, 1996.

This article was orginally published in On The Issues, Spring 2012.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed