Ada Dwyer Russell

Ada Dwyer Russell My question: Why would an aging B- or C-list actress choose the backbreaking and impecunious life of a touring performer over a retirement of ease and privilege with the woman she loved?

A little dramaturgical sidelight...

A little dramaturgical sidelight... ANYWAY... history gives us no answers, just clues. We know Ada turned Amy down more than once. We know that Amy was persistent to the point of bullying, and that when Ada did eventually agree to move in with Amy on her Boston estate, Sevenels, she insisted that it be for a trial period of six months, and that she would work and be paid as Amy's assistant, receiving the same amount of money she would have earned had she continued to tour as an actor.

And Amy Lowell was, frankly, a piece of work. I spent a lot of time studying her, as I adapted her writings for an evening of theatre. She emerges from letters and journals as a frustrated, spoiled-but-neglected, misunderstood child who developed into an intensely controlling and domineering woman.

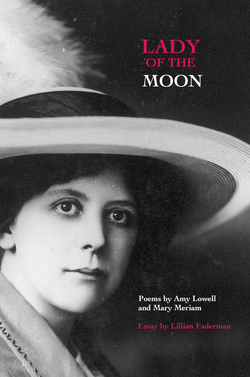

That's a younger Ada on the cover.

That's a younger Ada on the cover. Her fears appear to have been unjustified. Amy retained a respect bordering on worship for Ada for the rest of her life. She makes references to Ada in her poems as royalty, as a Greek goddess, and as a Madonna figure.

All too easy to caricature... fat, intellectual, and butch. Same as it ever was.

All too easy to caricature... fat, intellectual, and butch. Same as it ever was. It was a delight to revisit Amy’s poems. And Lillian Faderman’s essay (originally published in Surpassing the Love of Men: Romantic Friendship and Love Between Women From the Renaissance to the Present) illuminates them with historical context as well as a refreshingly lesbian perspective on Amy’s many critics. Amy was attacked, of course, for being a woman, for using her privilege to advance her interests (something men are expected to do), for being “mannish,” and for being fat. The poet Witter Bynner coined the term “hippopoetess” in reference to her, and Ezra Pound made sure that the epithet made it around the world. In response to this harassment, Lowell gave the world her prose poem, “Spring Day, Part One: The Bath.” She invites readers (and critics) to to envision her naked in her bathtub:

“The sunshine pours in at the bathroom window and bores through the water in the bath-tub in lathes and planes of greenish-white. It cleaves the water into flaws like a jewel, and cracks it to bright light. Little spots of sunshine lie on the surface of the water and dance, dance, and their reflections wobble deliciously over the ceiling; a stir of my finger sets them whirring, reeling. I move a foot, and the planes of light in the water jar. I lie back and laugh, and let the green-white water, the sun-flawed beryl water, flow over me..."

Pink Sweet Peas by Georgia O'Keeffe

Pink Sweet Peas by Georgia O'Keeffe "I put your leaves aside,

One by one:

The stiff, broad outer leaves;

The smaller ones,

Pleasant to touch, veined with purple;

The glazed inner leaves.

One by one

I parted you from your leaves,

Until you stood up like a white flower

Swaying slightly in the evening wind…

…The bud is more than the calyx.

There is nothing to equal a white bud,

Of no colour, and of all,

Burnished by moonlight,

Thrust upon by a softly-swinging wind."

The final section of the book fills in many of the gaps in the story unfolded in Amy’s poems. Here Mary Meriam gives imagined voice to Ada and Amy in a series of expressive poems, mostly in the sonnet form. I have a special appreciation of the sonnets that reference Ada's life in the theatre:

Mary Meriam, Poet

Mary Meriam, Poet I use the laughter, clinking, faint perfume

Of memory and fantasy to gauge

The time and distance to her dressing room…”

or…

“ … The play will end,

And then, what gesture will the world permit?

The players bow. The house begins to wend

Its way outside. I walk against the flow…”

Amy Lowell’s life and work have been treated with dismissal, with contempt, and with wild projection and distortion. Lady of the Moon returns her to us as a lesbian… and as a Muse. It is a testimony of the kind of blossoming that a woman can experience, especially a gender non-conforming lesbian, when she is fully seen and fully loved by another woman. I think of the great gentling influence that Ada had over this prickly and deeply damaged woman.

Female Rejection by Judy Chicago

Female Rejection by Judy Chicago And in Amy’s poetic tributes to Ada we see how it was actually Ada, all those years, folding back Amy’s stiff, protective leaves, revealing the inner sweetness of her lover, proving “the bud is more than the calyx.”

Footnote: Ada, by the way, outlived her younger lover by nearly thirty years, dying in 1952. Turns out she had good reason to be leery of wealthy people. Even though Amy had done all the legal work to leave her partner a lifetime interest in her estate, the surviving Lowells still found a way to evict her from Sevenels.

Another footnote: The book has a trailer!

And if you are interested in my dramatic adaptation of Lowell's work... Amy Lowell: In Her Own Words.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed