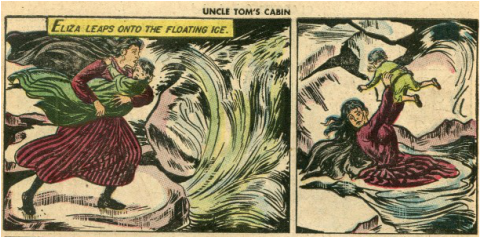

Excerpt from the comic book

Excerpt from the comic book As a child, I collected Classic Illustrated Comics, and every time there would be a new release, I would pester my mother to buy it for me. I remember the day in 1967 when the comic book adaptation of “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” appeared on the drugstore shelf. As usual, I asked my mother to buy the latest comic. When she saw the title, she suddenly became very frightened and, lowering her voice, she explained that it was a story that was very popular in the North, but that it was hated in the South. Born in Connecticut, my mother had fallen in love with a Southern sailor on leave in New York, married him, and moved to Virginia after the war. Pegged as a Yankee, she had initially been viewed with suspicion and snubbed socially. Apparently, my mother was afraid that someone might see her now, twenty years later, buying a children’s comic book, and that this could destroy her hard-won acceptance into Richmond society.

Fast-forward nearly forty years. The university theatre department in the city where I live is in an uproar. There had been a public reading of the dramatic adaptation of Uncle Tom’s Cabin as a collaboration between a drama lit class and a pop culture class. Some of the students felt that they had been compromised, because they had not been adequately informed about the historical context and controversy of the work before agreeing to participate.

I saw that reading… and here, as a playwright and an activist, is my reaction:

But what if a playwright wants to preach beyond the choir, to write a play for an audience that may actually be hostile to the message or paradigm being presented?

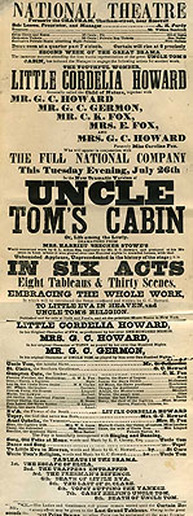

To answer that question, I am going to look at a play that is more than a hundred and fifty years old and still requires a trigger warning: Uncle Tom’s Cabin, based on the novel by Harriet Beecher Stowe and adapted by George L. Aiken.

Yes, I know that this play is considered the fountainhead of toxic stereotypes of African Americans that have poisoned the well of American drama and continue to seep into plays and films. I know that these stereotypes are so prevalent and so pernicious that the titular character’s name has become synonymous with “an epithet for a person who is slavish and excessively subservient to perceived authority figures, particularly a black person who behaves in a subservient manner to white people; or any person perceived to be complicit in the oppression of their own group.”

1987 film with Phylica Rashad and Bruce Dern

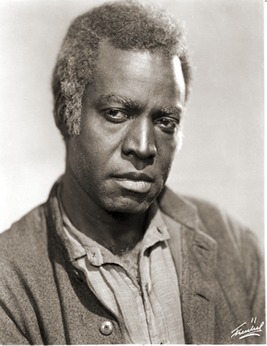

1987 film with Phylica Rashad and Bruce Dern  James Lowe in 1927 silent film version.

James Lowe in 1927 silent film version. Here is the irony: The very same dramaturgical strategies that enabled the play, back in the day, to preach so effectively beyond the choir are the reason why the play is vilified today.

African American writer and activist Toni Cade Bambara wrote, “The job of the writer is to make revolution irresistible.” She did not say that the job of the writer was to make sure that whatever strategies she employed in this work would remain revolutionary two hundred years later.

Stowe and Aikins managed to make sabotage, destruction of property, escape, armed resistance, and passive resistance irresistible to a population that would be the targets of these actions. They made revolution irresistible.

How?

This is from Our Gang's parody in 1926, but it is an accurate depiction of 19th century staging techniques of the escape scene. Click on the photo to watch it in action.

This is from Our Gang's parody in 1926, but it is an accurate depiction of 19th century staging techniques of the escape scene. Click on the photo to watch it in action. 1) Escaping. This is the least confrontational response, and therefore the one least threatening to white audiences. Stowe maximized this potential for identification by having her escapees legally married and light-skinned enough to pass. In other words, these characters would look like her audience. The couple has an infant son, and the family is threatened with forcible separation at a slave auction. The wife will be forced to submit to repeated rapes. Something we may forget today is that, up until the twentieth century, white audiences banned any representation of serious love between dark-skinned characters—just as they rejected the presence of Black actors in classical dramas. The denial of romantic or family ties was an ideology critical to the logistics of the slave auctions. This romantic, committed relationship at the heart of Uncle Tom’s Cabin was revolutionary in 1852. Stowe got away with it, only because she scripted it for light-skinned actors.

There is an adage in theatre that there is no right or wrong; there is only "boring" or "compelling." Aikins put Eliza’s flight across the semi-frozen Ohio River on the stage. With her pursuers and their dogs close behind, the distraught mother clutches her infant to her breast as she leaps to freedom from one chunk of ice to the next. Irresistible.

"Stealing" from the enslavers.

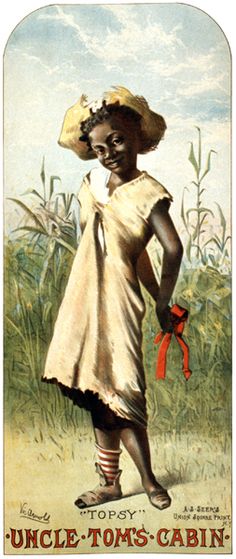

"Stealing" from the enslavers. Topsy is a wild child. She is paired with a racist, “Miss Grundy,” white, spinster stereotype. Her scenes are comprised of stock vaudevillian turns, where the working-class, down-to-earth stock character puts one over on their prissy and clueless, supposed “betters.” Topsy lies, cheats, steals, and intentionally destroys property… and audiences roar with delight every time she does. She gets an ovation for her standard defense: “I’m wicked, I guess.”

Topsy can be seen as a white fantasy of the unchristian savage, untamed and untameable, justifying the harsh abuse of enslavers. Both book and play, however, derail that interpretation by making explicit that Topsy was sold away from her parents as an infant, “raised by a speculator, with lots of others.” If Topsy has no loyalties except to herself, it is her enslavers who are to blame. Audiences are not allowed to forget that she has intentionally been deprived of any intellectual or moral instruction, and subjected to emotional, physical, and mostly likely sexual abuse.

A complicated killing.

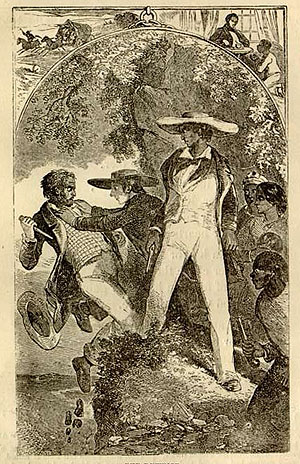

A complicated killing. Aikins pairs the escaping husband up with Phineas Fletcher, a white, working-class man who has recently converted to Quakerism in order to please his Quaker fiancée. Phineas is in the tradition of Shakespeare’s “rude mechanicals,” and his struggle to follow the pacifist teachings of the Quakers is a source of ongoing mirth for the audience. In the course of aiding George’s escape, the two men set up an ambush for their pursuers. George shoots one of his enemies, but audiences never know if the wound is fatal, because Phineas wrestles the man off the edge of a cliff. The killing is scripted as a moment of high comedy, because Phineas, mindful of his new religion, remembers to call out, “Friend, thee is not wanted here!” even as he heaves his enemy off the brink. White audiences roar their approbation.

What Aikins did was brilliant: The escaping captive shoots his enslaver, and does it onstage. The coup de grâce, however, is delivered by a white man sworn to a life of non-violence. The audience can choose where to put their focus. It doesn’t hurt that the scene, set in a mountain pass, is staged like a Western melodrama.

From Onkel Toms Hytt, a 1965 German film.

From Onkel Toms Hytt, a 1965 German film. Civil disobedience is no laughing matter, and so Stowe and Aikins turned to pathos. And hence the genesis of one of the most hated stereotypes in American drama: Uncle Tom.

Stowe and Eakins took pains to depict Tom as an enslaved man whose conversion to Christian ideals of loyalty, forgiveness, and meekness is absolute. His enslaver boasts that he can send Tom on errands to free states and count on him to return. Tom appears to be the ultimate white fantasy of an utterly subservient person of color.

But what people forget today is that, for all his over-the-top deference and humility, Tom is murdered for defying orders in the name of loyalty to a higher law. His first act of civil disobedience is refusing an order to whip an enslaved woman who is resisting the sexual advances of her enslaver. As a result, Tom is tortured. His second act is refusing to betray the escape plans of another enslaved woman who is faced with being sold away from her child. This time Tom is murdered. White notions of chivalry and Christian morality are pitted against audience members’ identification with being law-abiding citizens. When they approve of Tom’s defiance, they are assured that his disobedience is not motivated by self-interest or even disrespect. They are assured of this by the extravagant lengths to which Stowe went in characterizing Tom as a living saint.

Rape scene from the German version.

Rape scene from the German version. The horrific sexual violation of African American women is the engine that drives the play. From Eliza’s flight to Topsy’s wildness to the actions that precipitate Tom’s murder, the book and play portray rape and women’s subsequent lack of ownership of their children as the great evils underlying the institution of enslavement. Too often the abuse of African American women has been entered as an historical footnote to the Black Freedom Movement, if entered at all.

2011 saw the publication of Danielle L. McGuire’s book, At the Dark End of the Street: Black Women, Rape, and Resistance—A New History of the Civil Rights Movement from Rosa Parks to the Rise of Black Power. For the first time, there was a history book that wrote this violation back into the record. Few know that long before Rosa Parks refused to move to the back of the bus, she was engaged in advocating for social justice for black women who were the victims of sexual violence at the hands of white men. The previously unwritten history of the Montgomery Bus Boycott is a story of horrendous, ongoing sexual harassment and assault of Black women in these public conveyances.

Was this focus on women a passion of Stowe’s, a plea for historical accuracy, or a strategic device for recruiting audience outrage?

As a playwright, I come away from a study of this play with a different perspective on it, with a better idea of what it takes to preach beyond the choir, and the sobering realization that this preaching must engage with stereotypes and caricatures borne of my audience’s prejudice--in the risky hope of transforming them. This appears to be the price of making revolution irresistible.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed