!!!! A note about this series: These are posted in backwards order (it's a website thing...), so PLEASE GO TO PART ONE (click here) now to start the series. There is a link at the end of each one that will take you to the next. Sorry for the inconvenience. !!!!!!

Okay… This is the final blog on Anatomy of an Epidemic: Magic Bullets, Psychiatric Drugs and the Astounding Rise of Mental Illness in America.

In 2003, there was an interesting hunger strike by six “psychiatric survivors” from MindFreedom International, a patients’ rights organization. It was a pretty simple hunger strike. All they were asking was that the American Psychiatric Association, or the National Alliance on Mental Illness, or the Office of the Surgeon General provide scientifically valid evidence for the stories they were telling the public… i.e:

1) Evidence that major mental illnesses are biologically-based brain diseases.

2) Evidence that psychiatric drugs can correct chemical imbalance in the brain.

And then they made a reasonable request: That, if these organizations could not meet the request, that they admit to the public that they are unable to do so.

They never received any evidence, and, not surprisingly, none of the organizations made any public announcements. But the strikers did manage to get some press. I wish they had gotten more, and, as one of them noted in 2009, “I think it’s time for another hunger strike.”

Here’s the deal: Some of these drugs do alleviate symptoms in the short term, and there are some folks who stabilize over the long term on them. There is a use for them, as the author acknowledges, in the “psychiatry toolbox.” The problem appears to be a lack of honesty in how they are presented to the public. The public has a right to know:

- That biological causes of mental illness remain unknown.

- That drugs do not fix imbalances in the brain, but perturb normal functioning of neurotransmitter paths.

- Long-term studies reveal that the medications worsen long-term outcomes.

- That many people who experience deep depression can recover naturally and that long-term use of psychotropics is associated with increased chronicity.

The author spends some time visiting psychiatric facilities in Western Lapland. Here, patients are treated to something called “open-dialogue” therapy. The nurses, psychologists, social workers, and psychiatrists have, for the most part, completed a three-year, 900-hour course in family therapy. According to psychologist Tapio Salo, “Psychosis does not live in the head. It lives in the in-between of family members, and of people. It is in the relationship, and the one who is psychotic makes the bad connection visible. He or she ‘wears the symptoms’ and has the burden to carry them.”

Wow. And, even though this practitioner is referring specifically to psychosis, I felt when I read those words that they potentially have much wider application. What if all the folks who bought into the myth of “chemical imbalance in the brain” were to switch over to an understanding that mental illness resides in the spaces between people… between family members, certainly… and friends, but also members of one’s church, classmates, co-workers, between a government and a people, and between other species and ourselves? What if we all took that seriously and began to put the focus on treating those relationships as if our sanity depended on it?

But let’s go back to this “open dialogue” in Western Lapland. Everyone goes to the first meeting with family and patient with the awareness that they “know nothing.” Wow. Really? Yes, really. Those 900 hours have trained them all to be “specialists in saying that we are not specialists.” In fact, the therapists consider themselves guests in the patient’s home. If the patient runs off, they just ask them to leave the door open so they can hear the conversation.

There is no mention of antipsychotics in the first few meetings. If the patient begins to sleep better and bath regularly, and in other ways reestablish societal connections, the therapists see that the “grip on life” is strengthening and meds will not be needed. Sometimes benzodiazepenes are given short-term for anxiety or sleep problems, but when the problem goes away, the meds are stopped.

Yes, this process takes time. Sometimes up to five years. Teachers and prospective employers are asked to join the dialogue. The focus is on restoring social connections.

What about alternative therapies for depression? 70% of depressed patients respond to an exercise program. In fact, general practitioners in the UK are writing prescriptions for exercise. And the side effects are fantastic: more strength, better cardiovascular function, lower blood pressure, better sleep, better sex, improved cognitive functioning. Oh, and studies have shown it is not wise to combine exercise with drug therapy.

Then there is the Seneca Center in California, a last-stop for severely disturbed kids. When a child enters the residential program, the question is not “What’s wrong with the kid?” but “What happened to them?” The Seneca Center also does something else interesting. As they chart the life history of the kids, they also chart the medication history… looking for how behavior may have changed after medication. Not surprisingly, these histories regularly tell of psychiatric care that has worsened behavior. If they can see that a drug did not help, they don't prescribe it.They frequently detox the kids and institute behavior modification techniques to help the kids control their own behavior.

According to the program director, “… feeling in charge of yourself and being responsible for yourself is [sic] the central issue of their lives.” It’s about power. And power in relationships. They provide “mentors” for the kids, and the kids learn that it’s safe to form attachments.

The Seneca Center highlights a major issue in mental health today: The need for social and medical support for detoxing from prescription medications.

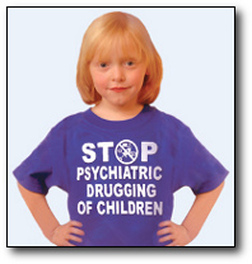

Gottstein has moved on to filing lawsuits on behalf of foster children and children living in poverty. He likens these suits to Brown vs. Board of Education, hoping they will have a similar effect to that watershed lawsuit that ended segregation—in this case changing national attitudes about the drugging of children.

There’s no neat way to sum up these ten blogs. Obviously, I consider it an important book. As an activist, I have seen a country and a generation of activists become progressively more numb and more complacent. I have seen friends change personalities, stop moving forward. I have experienced the suicides and attempted suicides of friends and colleagues—four in this last year. As global warming advances, as resources become more scarce and economies more fragile, as social services are increasingly cut, and as the environment becomes more and more toxic, there has never been so great a need for awareness, for clarity, and—yes—alarm. It is a time for radical honesty, for confrontation of the conflict-of-interest when drug companies have so many financial ties to Congress, to doctors, and to medical schools. It is time for honest studies, for “open dialogue” on a national level.

What I take away from the book, and take most seriously, is a new understanding that mental illness resides in the spaces between people. I want to take responsibility for my part in the healing of that space.

Click here to go back to Part 1.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed