Dame Helen Mirren as a cross-gendered Prospero ("Prospera") in The Tempest

Dame Helen Mirren as a cross-gendered Prospero ("Prospera") in The Tempest But, of course, Shakespeare was a man. Not just a man, but a man writing for theatre companies that were all-male. And, on top of that, his plots often reflect the stories of kings and princes and military leaders. Not surprisingly, the roles for men outnumber those for women five-to-one, with all of the major characters being male.

In recent decades, we have seen an increase in women cross-dressing some of these roles, and even all-women productions. Why not? Acting is acting. If we can pretend to be Lady Macbeth, why not Macbeth himself? If Shakespeare’s actors could impersonate women, we can certainly have a shot at his male roles.

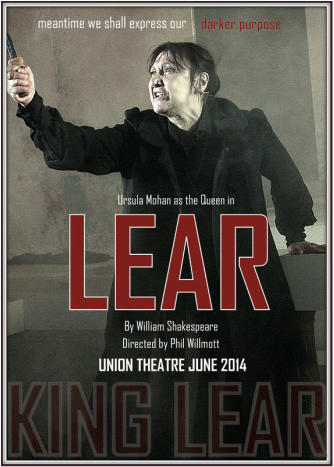

Ursula Mohan as Queen Lear in 2014 production.

Ursula Mohan as Queen Lear in 2014 production. This is what I want to talk about—this cross-gendering of Shakespeare.

Some celebrate this as a kind of bringing down of the dramaturgical Berlin Wall between the sexes. I actually see it as a form of shoring it up.

Before I explain, I am feeling a need to put out some of my credentials in the gender-bending department. My first directing project as a theatre major was an all-female, cross-gendered production of Edward Albee’s The Zoo Story. The actors played the roles of Peter and Jerry as women. I considered this very daring. I remember that I did make one adjustment… small, but significant. Jerry’s use of pornography did not resonate for me in the landscape of lesbians in the early 1980’s. This was before the Internet and before the rise of lesbian pornography. I switched the reference to romance novels, which women did and still do consume in mindless quantities in order to generate feel-good endorphins. It seemed to me to be the female counterpart to porn.

A cross-gendered production of The Zoo Story (not mine...)

A cross-gendered production of The Zoo Story (not mine...) My production, in spite of my best efforts, lacked integrity. The women’s final choices appeared to be senseless, sensational violence. They had no historical precedent (the class tensions between gay males, with privilege temporarily and superficially leveled by shared outlaw status), and no social context (cruising in a New York City park), and no established archetypes (the middle-class, closeted family man and the youthful, gay street hustler). I liken my cross-gendering of the play to the wearing of “boyfriend jeans.”

Boyfriend jeans.

Boyfriend jeans. My production of The Zoo Story was clad in Albee’s “boyfriend jeans.” Yes, my production had a toughness, a sense of daring, a kind of tomboy swagger that was rare in the early 1980’s world of women’s plays. We were not doing a romantic comedy. We were not accepting the roles for women created by male playwrights. We were not doing a Wendy Wasserstein coffee klatsch, or a Megan Terry hippie play. We were hefting beefy chunks of tough male dialogue and heaving them into the gaping maw of our rabid male critics. Or so we thought. In fact, we were prancing around in “boyfriend jeans.” Nobody mistook our production for The Zoo Story… except us.

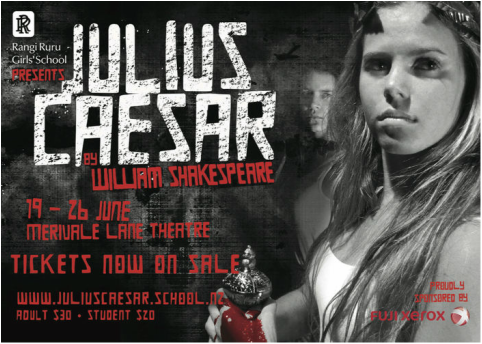

A cross-gendered Julius Caesar at a girls' school in New Zealand

A cross-gendered Julius Caesar at a girls' school in New Zealand This was territory we both understood. This was the no-woman’s land we had both learned to navigate in our careers. We knew the game completely, but when the conversation shifted to interpretation of the role of Cassius, we lost our footing. Because in this production, the women were supposed to share power with the men. It’s called “gender-blindness.” But we did not have gender-blind words. Cassius’s speech was written by one man for another man, who would be portraying a male character who was in the political elite of an all-male government in a country where women had almost no rights, no financial independence, and no political voice or presence whatsoever. There was no inner truth, no integrity to the interpretation, because neither of us had any cultural referent for “gender-blindness.” It is not possible to act political idealism. If it were grounded in any reality that could be embodied, it would not be idealism. Duh. Boyfriend jeans.

Another "Queen Lear," in a Colorado theater.

Another "Queen Lear," in a Colorado theater. What are we talking about with Queen Lear? There is no woman, especially of a royal family, and especially as the head of that royal family, who lives outside of patriarchy. There is no mother whose relationships with her daughters has not been shaped by some dance of compliance and resistance to that patriarchy. I felt that the girls were being taught to believe that power was a question of temperament, of personality, and that it existed apart from social systems, historic precedents, political realities. The dreadful unraveling of Lear’s kingdom, family, and sanity are testament to the rigidity and distortions of a patriarch whose will has gone unchecked for his entire adult life. His ownership of his daughters was a legally defined relationship that informed his fatal choices. Well, I could go on. It was boyfriend jeans again, and the girls were getting a ton of props for parading around in them.

The problem I have with cross-gendering these roles is two-fold: They cannot provide powerful material for the actor. That fish-on-dry-land thing. Acting in a vacuum. Dialogue from a science fiction world that the director fails to establish and that the playwright never intended and that is not the actor’s job to create.

The second problem I have is more serious: The masking of the very real patriarchal context that pervades the world of Shakespeare’s plays and which his narratives continually expose and challenge. Hamlet gets in trouble, because the son of a warrior king cannot be allowed the contemplative bachelor life of a poet and philosopher. King Lear is a cautionary tale about even the so-called winners in a patriarchal hierarchy, because old age and impotence catch up to us all. And so on.

Curio Theater's lesbian Romeo and Juliet

Curio Theater's lesbian Romeo and Juliet The good news—the very good news— is that women have found our voices now, and some of us are actually writing classical dramas with large casts and epic themes. Ahem. I have several, myself. Just ask.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed