I liked the original graphic memoir, Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic. I thought it was brilliant, overwhelming, honest, searing… and a masterful execution of graphic art. I thought it deserved the American Book Award and the Lambda Literary Book Award.

So why did I feel so differently about the musical? To be perfectly honest, I have not worked that out yet. But I do have some ideas. First, musical theatre is a very different genre than a memoir, even when that memoir is an illustrated one.

Theatre has its own conventions and tropes. The American family is a familiar subject for American theatre: Raisin in the Sun, Fences, Long Day’s Journey Into Night, The Little Foxes, Fifth of July, Brighton Beach Memoirs, Awake and Sing, August: Osage County, Death of a Salesman, and so on. The yearning for connection with an emotionally unavailable parent is a frequent theme. These family dramas are filled with bittersweet nostalgia for a bygone era and the lost innocence of childhood. And of course infidelity and broken homes are also common themes.

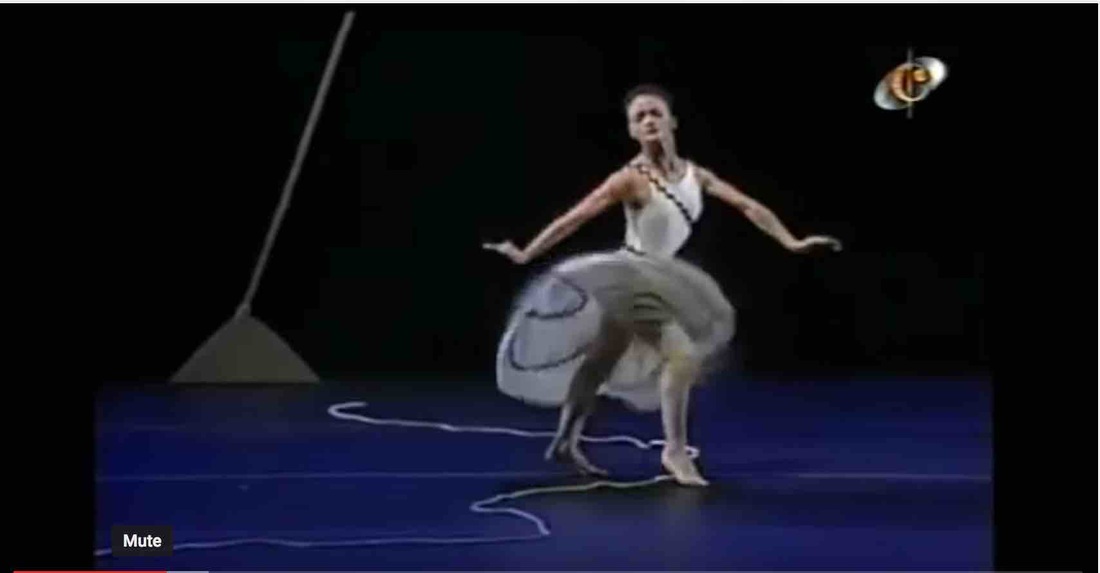

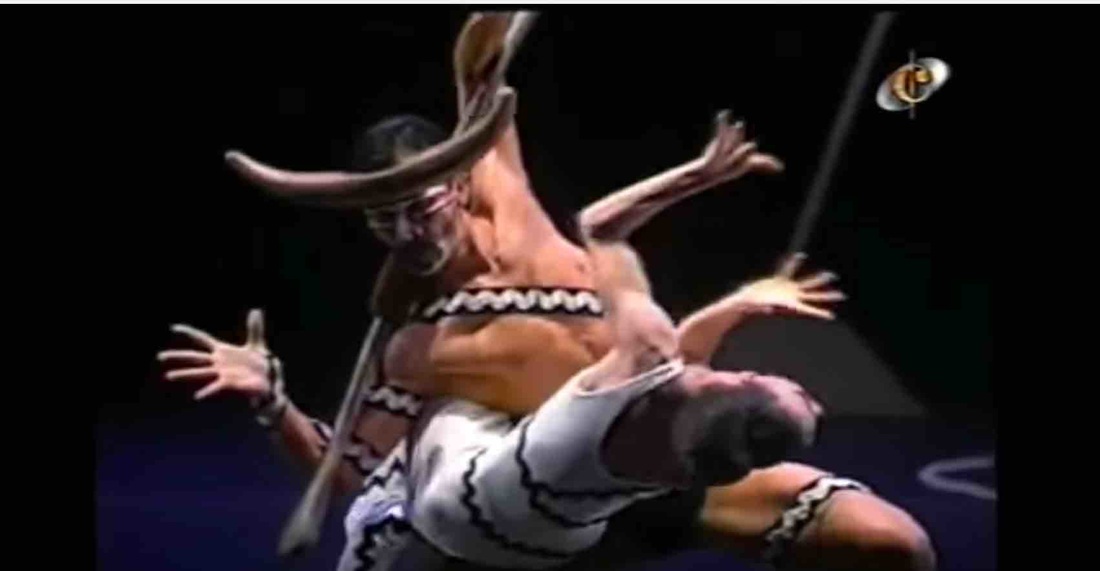

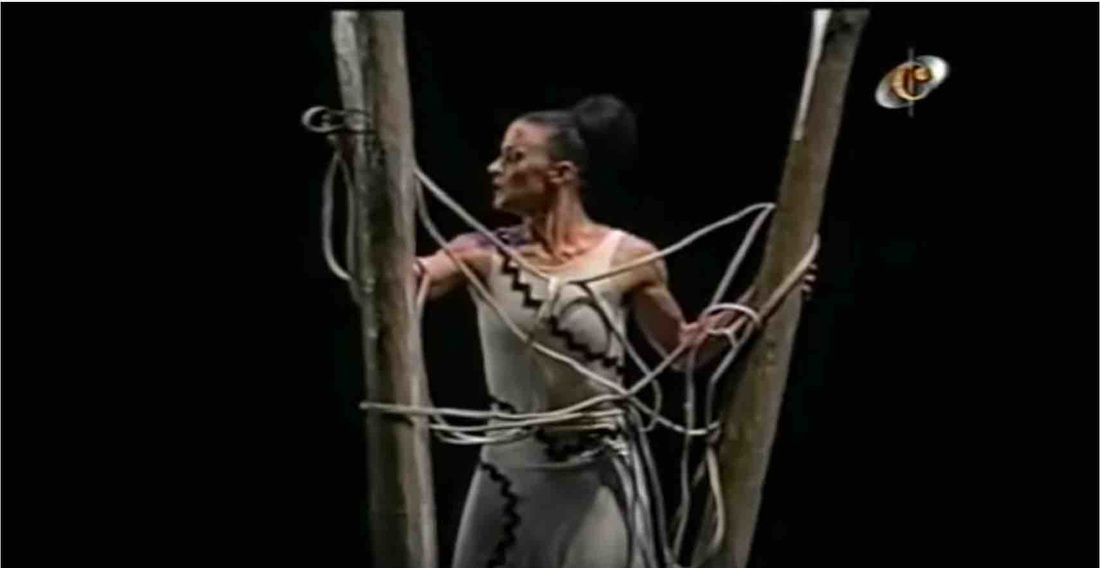

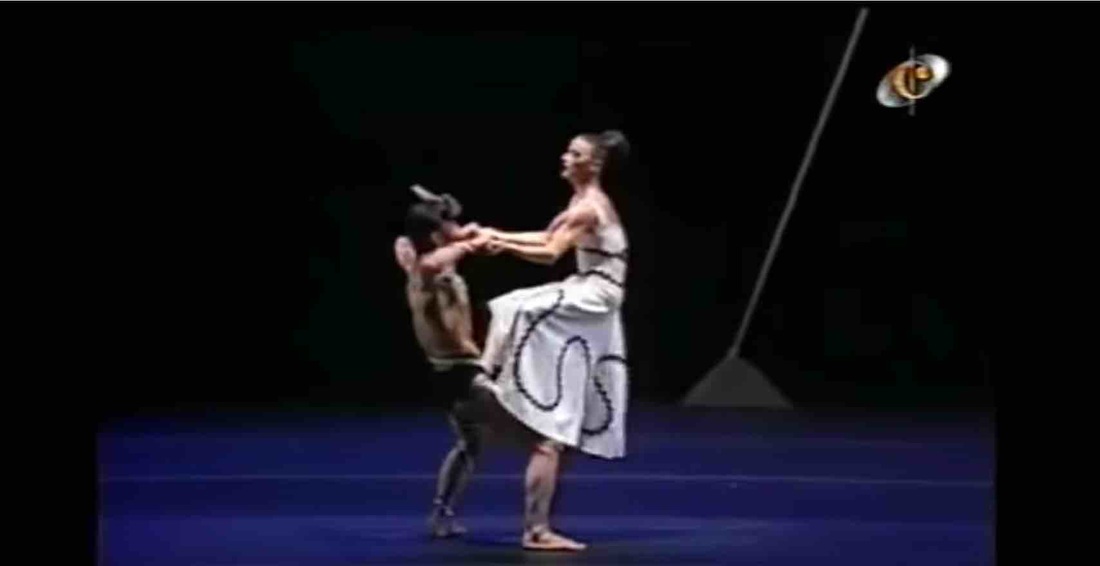

Montage of various musicals

Montage of various musicals Also, authorship is important. The writer of a memoir is telling her own story, often with a motive just to get it out and on paper. The musical-theatre adaptors of a best-selling memoir have a different motive. It’s not their story, clearly. They are incentivized to tailor the material to the genre. I may or may not agree with the memoirist’s perception or interpretation of her experiences, but I appreciate that she is entitled to her confusions, her “in-process” status as a human being. She is inviting me to look over her shoulder and I am aware that this is a privilege.

Musical theatre is something different. It is an incredibly powerful medium, and I am acutely aware of when and how musical theatre can be used to manipulate emotions and reshape values.

So… at this point, let me just move on to my objections…

Teacher at international schools and serial pedophile William Vahey. He abused scores of students and three of his victims took their own lives.

Teacher at international schools and serial pedophile William Vahey. He abused scores of students and three of his victims took their own lives. In the musical, three actresses portray the different incarnations of the protagonist at different ages in her life. “Small Alison” is a little girl, “Medium Alison” is a budding lesbian in her first year of college, and “Alison” is an adult cartoonist in mid-career, in the act of creating the memoir that is the basis of the play. The plot turns around all the Alisons’ relationship to the father.

In the musical, the child sexual abuse is obliquely alluded to, but only presented factually in one line of a song sung by the mother. The song is a lament about her husband’s adultery and the line is, “some of them underage.” That’s it. The pedophilic predation is presented as a footnote to the father’s infidelity and his homosexuality. It’s also presented as a victimless crime. The reactions of all the characters are consistent with those of a family who discovers a history of cheating by the patriarch. It’s a play about a cheater, not a criminal sexual predator. It’s about adultery, not child rape.

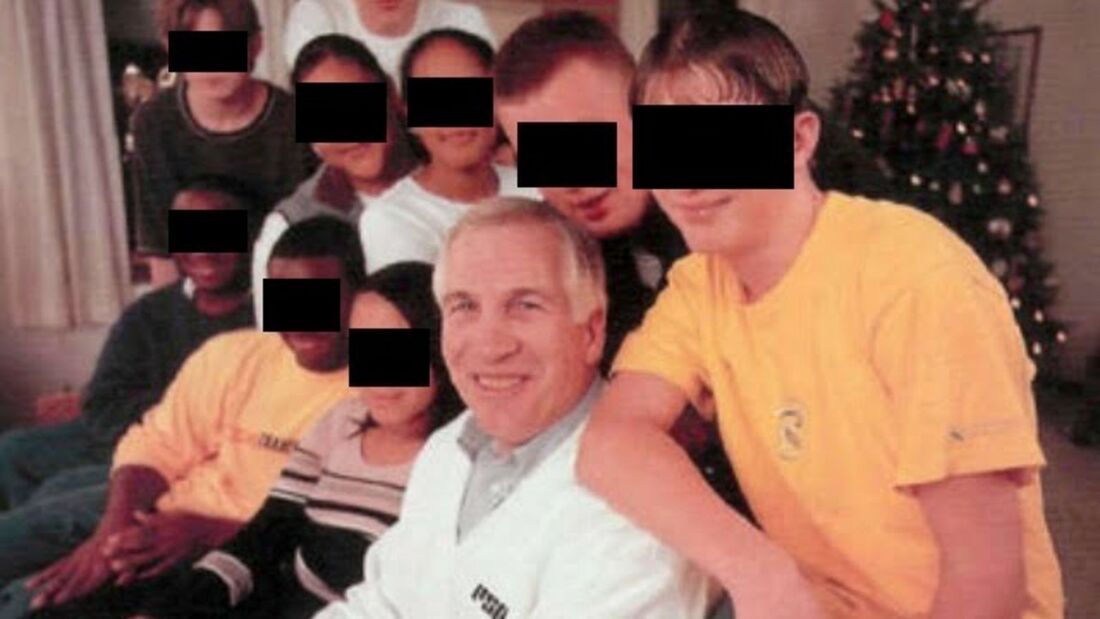

Penn State football coach and serial pedophile Jerry Sandusky convicted on 45 counts of sexual abuse of boys over a period of 15 years.

Penn State football coach and serial pedophile Jerry Sandusky convicted on 45 counts of sexual abuse of boys over a period of 15 years. I get it. All of this must have been overwhelming for a nineteen-year-old. I see why it took decades for Bechdel to be able to write about it. I see why there are so many conflicting emotions, so much confusion in the telling. These are all reasons why her story makes for such a powerful memoir. And they are all reasons why it should never have been shaped into a mainstream musical about a dysfunctional American family.

Here is my question to theatre audiences who love Fun Home: What if the family secret was that the father had been stalking and murdering his students and his barely-legal, former students, but the dialogue had remained fixated on his cheating and the daughter’s desire for connection with him? Would that have changed your experience of the play?

I ask this, because, for me, as a survivor of child sexual abuse, I experienced the father as a kind of serial murderer. He was a murderer of childhood, a soul murderer. I sit in meetings with grown men who were the teenaged victims of men like Mr. Bechdel. I hear how they were confused, how some of them believed they were consenting or participating at the time, how it took them years to remember, to sort out the shame, to figure out what their sexual orientation was, or even just to recognize that they had been victimized. It took them decades to trace their self-harming behaviors and addictions back to the betrayal by their trusted teacher, priest, parent, and so on.

USA Gymnastics national team doctor and serial pedophile Larry Nasser. 100 athletes came forward to accuse him.

USA Gymnastics national team doctor and serial pedophile Larry Nasser. 100 athletes came forward to accuse him. When one is in a family, a difficult family with complicated and damaged individuals each struggling with their personal demons… and then it is revealed that one of them is a child-raper, the entire paradigm should shift. Every memory should become subject to revision, every emotion cut loose from its moorings. Trauma occurs. Something utterly unthinkable, completely unacceptable must be thought, must be accepted. But it can’t be. But it must be. But it can’t be. And that schism, that impossible conundrum, that trauma, is what happened to me in the theatre, because the writers of the show chose to elide the criminal behavior with sexual orientation and adultery.

Here is another question: What would Fun Home look like if the members of the family came out of denial and responded appropriately to information that the father is a pedophilic predator?

Art by Katie M. Berggren

Art by Katie M. Berggren She sings a song, “Oh, my god… I didn’t know… and yet… those boys… those boys he taught… Oh my god… I didn’t know… And yet my mother did… And yet my mother stayed… And those boys… those boys…”

And then we see Small Alison and Medium Alison appear. They are both frightened. Alison puts her arms around both of them.

And then the Boys appear, one by one. They each sing a song about the time Mr. Bechdel picked them up when they were walking on the road and how he offered them beer, even though they were underage. They sing how he said he would take them home and then drove them somewhere else, to “get to know them.” They sing about the time he hired them to work in his yard. They sing their stories… and then their adult selves appear and sing about the years of doubt and shame, the nights of terror, the secrecy, the sexual confusion, the self-hatred, the shattered relationships, the addictions.

The Boys fade into the shadows and Small Alison starts to sing a song she opened the show with: “Daddy! Hey, Daddy, come here, okay? I need you/ What are you doing? I said come here…” Alison stops her and sings about how she, adult Alison, will take care of her now. She tells Small Alison that her father is gone forever, but that she doesn’t need to be afraid, because adult Alison will be her parent now.

Alison and Small Alison end the show standing together. Alison explains to the child how they can never go home again, but that they can go forward and help the children like the Boys their father victimized. She sings about how they can tell their story to help victims be believed, to show that they don’t need to feel ashamed about what happened to them, but that they can find other survivors and build a different world. She tells her that it is not up to them to find a way to patch up or save the family. It’s gone.

Would my version make it to Broadway and win a Tony for “best musical?” No, of course not. For starts, there is a huge continuity problem. It’s actually made up of two completely different plays: the slightly comedic, dysfunctional dramedy and then the shocking paradigm shift. Which is the experience of child sexual abuse. Welcome to my world. The perpetrator’s suicide is not only not the dramatic climax, it’s not even relevant. There is nothing bittersweet or sentimental about the situation. The closure must occur outside of the family, in affiliation with other survivors.

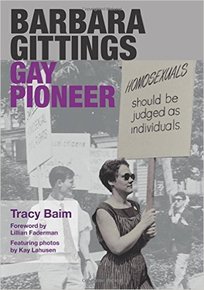

Former Miss America and incest survivor/activist Marilyn Van Derbur. Over the past 20 years she has spoken in more than 500 cities. She is the author of Miss America By Day, her story of abuse.

Former Miss America and incest survivor/activist Marilyn Van Derbur. Over the past 20 years she has spoken in more than 500 cities. She is the author of Miss America By Day, her story of abuse. In conclusion: We need to hear the voices of survivors. #MeToo is old news to most women. The only thing trendy about it was that men are believing us for the first time. For all the publicity and Congressional hearings about rape in the military, sexual assaults are at the highest levels ever this year. And no, it’s not about “better reporting.” Stop that. Child sexual abuse and trafficking are big business globally, and the Pope has still not mandated reporting child-rapists to civil authorities. That’s an outrage. Broadway’s response to sexual harassment in the academy was Oleanna, a play about those manipulative lesbians in Women’s Studies encouraging false accusations against innocent men. Broadway’s response to the priesthood scandals? Doubt, whose title says it all. Prostitution? How about Best Little Whorehouse in Texas?

We all have to speak up. We really do. And it’s always going to feel scary. Do what you can. I gave Fun Home a standing ovation, because I was in a post-traumatic panic attack when the curtain went down, and I felt it was the more dangerous choice to draw attention to myself by staying seated. But I am home now. I have gathered Small Carolyn and Medium Carolyn and all the others around me, and together we are writing this blog.

Love to all my survivor brothers and sisters. You are not alone. “We must say to every member of our society: If you violate your children, they may not speak today, but as we gather our strength and stand beside them, they will, one day, speak your name. They will speak every single name.”—Marilyn Van Derbur

Thanks to Eleanor Cowan, the author of A History of a Pedophile's Wife: Memoir of a Canadian Teacher and Writer, for her feedback on this blog. Click here for my blog about her book. I have several blogs on the subject of child sexual abuse and incest.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed