The "Neue Frau" or "New Woman" of Weimar Germany

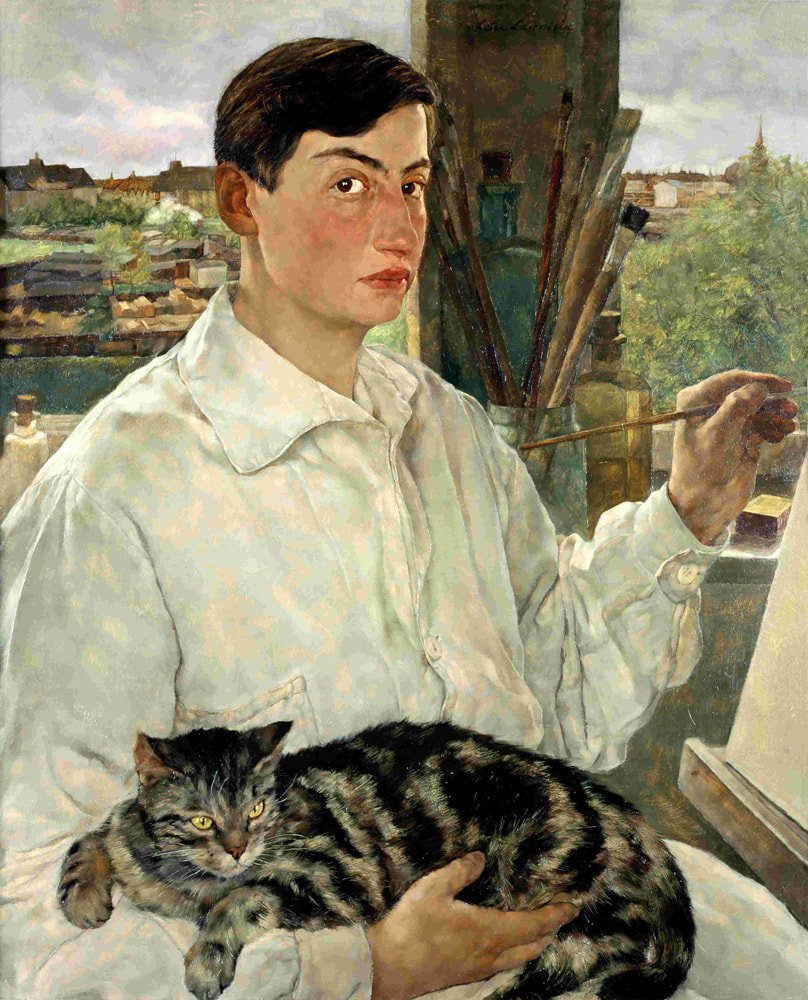

The "Neue Frau" or "New Woman" of Weimar Germany German-Swedish, lesbian painter Lotter Laserstein not only made herself that “small republic of unconquered spirit,” but she created a body of work that documents that Amazonian domain. Most remarkable, she did this in Germany during the rise of the Nazi party.

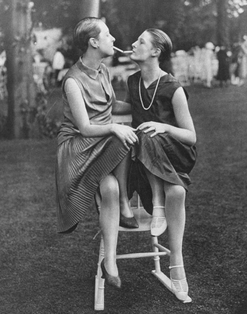

Laserstein painted “In My Studio” at the age of thirty. The year was 1928. She had just graduated from the Prussian Academy of Fine Arts. It was a time of uncertainty and also exhilaration. For the first time, women were allowed to attend public art academies. For the first time, women were allowed to attend nude figure drawing classes. For the first time, women were allowed to sport traditionally male haircuts, the “Eton crop” or the “bubikopf.” They were allowed to wear straight-waist dresses and tuxedo jackets. The “Great War” had opened up employment in traditionally male trades and professions. Women had their own money and began to exercise their autonomy in ways that would have been inconceivable to their mothers.

"La Grande Odalisque"

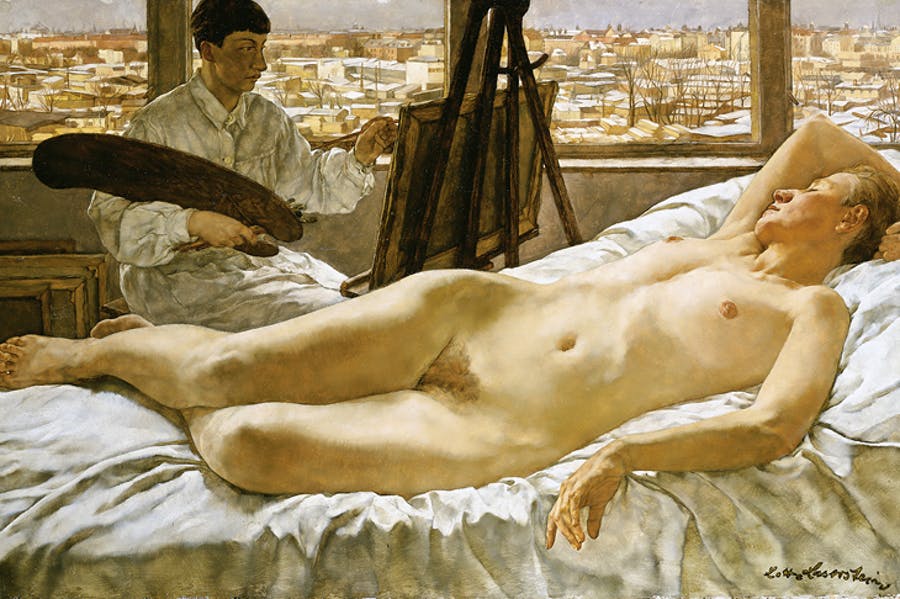

"La Grande Odalisque" And what was happening in this studio of hers? No less than a miracle. Laserstein is painting a female nude, the traditional subject of centuries of male artists. An internet image search for “odalisque” will turn up hundreds of images of reclining female nudes. According to art historian Joan DelPlato, “By the eighteenth century the term odalisque referred to the eroticized artistic genre in which a nominally eastern woman lies on her side on display for the spectator.”

Sadly not unusual

Sadly not unusual And what about this model? Her name is "Traute Rose," and was a model noted for an athletic and androgenous physique. Laserstein not only told people that Traute was her favorite model, but their intimacy is the subject of a number of her paintings... paintings that the artist would refer to as collaborations between her and Rose. In a letter to Rose in 1956, Laserstein was describing a painting of a nude that she was then working on, noting that it was “far from being as good as ours.” The relationship between male painters and the female nude models has historically been hierarchical, with the dominance of the painter made explicit in the paintings where they appear together. Lasertein’s portraits of Rose bear witness to their mutuality and the trust between them. They appear to share an artistic investment in the painting. It is not a commercial relationship.

The figure of Rose in "In My Studio" has been referred to by art critics as monumental. She sprawls across the foreground, and there is absolutely no attempt to titillate the spectator with partial concealment with drapery. The model is lost in her own thoughts, or perhaps asleep. There is no "come hither" expression. Her face is turned toward Laserstein, not us. Traute Rose, with her small breasts, her “Eton bob,” her lack of makeup, and her large and muscular hands, defies the expectations of "the male gaze."

Laserstein foregrounds these hands and the gender non-conformity of Rose in her painting "The Tennis Player."

Laserstein's career, which had taken off so quickly and which was gaining so much recognition, was cut short and she was forced to start over in a foreign country where she did not speak the language. To survive, she painted portraits for members of the upper class. Word of mouth spread rapidly, and she became a successful painter who would eventually be able to afford a second summer home. But it came at a price: She had to paint what her clients wanted. The days of spending hundreds of hours painting rooftop Bohemian friends and nude portraits of her beloved Rose were over. Painting was a business now.

The war took a tremendous toll on Laserstein, as she struggled to learn a new language, to rebuild a career, and to help family members trapped in Germany. The boldness, ambition, and vision, so evident in her early works are absent from the Swedish years. Her life and her work had become about survival.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed